Diverse Books Review Series- Wishes + Wherever I Go

A very special thanks to I’m Your Neighbor Books for making these texts available for review.

Looking for ways to incorporate diverse books into your library or classroom programming?

Visit https://imyourneighborbooks.org/ for valuable tools, resources, projects, and book searches.

While you’re there, be sure to check out The Welcoming Library, a pop-up community conversation on immigration.

Title: Wishes

by Mu’o’n Thi Van & Victo Ngai

Empathy is a pillar of social-emotional learning. And it’s more important now than at any other time in our collective history. Wishes, by Mu’o’on Thi Van is an experience in empathy and human connectedness from its first page to its last.

This powerful early reader grabs you in its first moments. Victor Ngai’s beautifully rich illustrations wrap the text in a blanket of emotional imagery.

The night wished it was quieter. The bag wished it was deeper.

The story illuminates the realities of human migration as it takes readers along a path of goodbyes, uncertainties, and ultimately, hope. The writing takes on the lens of various elements along the journey- the path that wished it was shorter, the boat that wished it was bigger, the heart that wished it was stronger.

Incredibly, Mu’o’on Thi Van makes tough content digestible for young readers, but that also leaves space for open-ended questions, critical text connections, and constructive upper-grade conversations.

I can simultaneously imagine this book as a first-grade read-aloud, as part of a second-grade lesson on personification, as the bones for a fourth-grade art study, as a middle school drama reconstruction, and as the foundation for a high school essay. And I’m definitely purchasing a copy for our children’s bookshelf at home.

Through its meticulously detailed artwork and profoundly simple text, Wishes is a very natural practice in empathy. It unassumingly invites readers to exercise muscles of understanding, connection, and inclusivity. For many young folks, I expect that it will also light a fire of curiosity, if not deliberate activism.

If you’re searching for a text that dives into the refugee experience while maintaining a lens on the human story, Wishes should be a first pick.

Title: Wherever I Go

by Mary Wagley Copp & Munir D. Mohammed

Wherever I Go is the anthem of young Abia, a queen by all accounts. Abia’s entire youth has occurred within the Shimelba refugee camp. However, this fact has nothing on the girl’s spirit.

Wherever I Go shines a light on what life in a refugee camp can be like. But despite glimpses of daily hardships- pumping and carrying water, of waiting in long lines for rice and oil, of caring for younger siblings- this isn’t a story of defeat. Indeed, Copp and Mohammed offer up characters full of dignity, strength, bravery, and optimism.

Munir Mohammed is a perfect fit for this book. His vibrantly colored full-page illustrations make me feel like I’m sitting across the mat from Abia’s parents myself, like Abia’s father, in particular, is someone I’ve known already. Simply stunning.

Eventually, the family prepares for their turn to come up for resettlement. And when we go, we’ll leave our belongings here- for others. That’s what Papa says. “Everything,” he adds. Mama says we’ll have our stories, though, wherever we go.

The book closes with Abia settled into her new life, somewhere on the other side of the ocean. At this point, however, the reader knows that with a spirit as tenacious as Abia’s, this queen’s story is far from over.

Copp and Mohammed invite readers to consider the main character’s pre and post-resettlement identity and do so in a way that is culturally affirmative. This lens highlights those threads that link both worlds- family, hope, perseverance, and the idea of home.

If you’re considering having students consider their own stories and what they take with them wherever they go, I can’t imagine a better starting point.

TIII Back-to-School Series: Visual Orientation Handbook

I absolutely love this idea of a visual orientation handbook, shared with me by Silvia Tamminen, coordinator at the Aurora Public Schools (APS) Welcome Center in the Denver suburb of Aurora, Colorado.

The Aurora Public Schools (APS) Welcome Center supports one of the most diverse student populations in the country. This demographic includes a large number of folks resettled refugee status. The district is now home to students from all over the world, with especially robust cultural representation from Bhutan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Libya, Syria, Myanmar, Côte d’ Ivoire, and Eritrea.

Families with school-aged children who are new to the district and also new to the English language are directly referred to the APS Welcome Center. Staff guide Newcomer families through the processes of student registration and school orientation.

Sylvia Timmenem heads this effort. She’s a human rights professional with a concentration on refugee and migration issues. Her knowledge of policy and practice is evident. But she’s also approachable and down-to-earth, with a bold, welcoming smile. As I glance through her workspace, I notice elements of her Fin culture.

“Immigration is something I share with our clients,” she tells me. But she’s also quick to point out that while there are some parallels, her path to America was smoother than many of those she sees in her day-to-day work. Sylvia is deeply aware of the privilege that comes with choice, with a previous knowledge of the English language, and even her appearance. Nonetheless, she does have an understanding of just how complex and overwhelming the immgration process can be. This awareness adds an additional layer of humanity to her interactions.

Sylivia came on board with the APS Welcome Center program in its inaugural season. She and her team built the organization from the bones up. The visual orientation handbook is among the group’s creative, solution-seeking efforts.

The handbook is a non-consumable resource with a permanent home in Sylvia’s office. It is composed of full-page photos and illustrations, slid into sheet protectors and organized into a three-ring binder. Each image is captioned with a simple explanation, which is (or can be) easily translated into a preferred language. Sylvia or another APS staff member reads the book alongside incoming families (and a translator, if requested). Page by page, the tool lays out the expectations for a typical school day.

For example, one picture shows a group of students sitting on the ground listening to a read-aloud. The caption reads, “Sometimes, students sit on the carpet during the school day.”

This was an important inclusion, Sylvia assured me. “Many times our parents cannot believe that their child would sit on the floor to learn anything. In some of their own countries, that would be very strange and maybe make a parent very angry.” She points out that often these seemingly “everyday” aspects of the school day can be overlooked. But in the context of welcoming families from culturally diverse backgrounds, taking the time to explicitly detail various aspects of the school experience can go a long way.

Here are some other situations included in the APS visual orientation handbook:

Kids receiving lunch on a tray (many recently arrived learners would have gone home for lunch or packed their own meal)

Young adults putting their supplies in lockers (this may be a first-time experience for many)

Students arriving for school at or before the scheduled time (concepts of time and urgency around timeliness varies greatly from one culture and context to another)

Photos of co-ed teaching staff (learners and their families may have culturally influenced expectations about the appearance of those in teacher and leadership roles).

There are plenty more great ideas. Check them out in the Aurora Welcome Center’s comprehensive list below!

Could you duplicate this resource at your site? As long as you have a camera and a few hours to spare, of course! (Just be sure to send out a thank you to the APS Welcome Center for the idea. Find them here: http://welcomecenter.aurorak12.org)

This version was created by staff. But other great options might include:

Inviting former Newcomers to take this on as a project (a modernized “buddy” system)

Creating a digital and/or interactive version of the handbook

Engaging teacher teams in creating grade-level welcoming handbooks

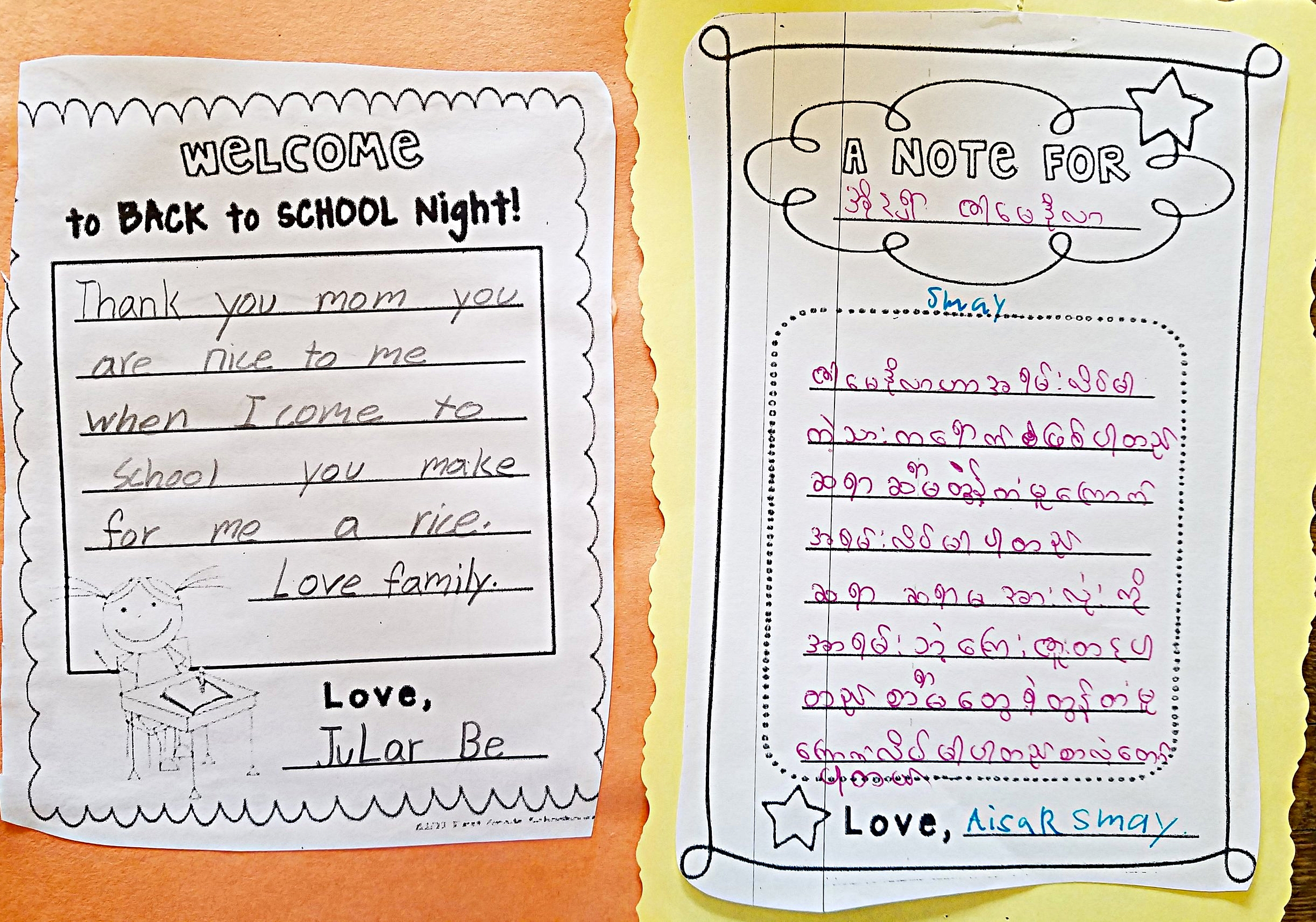

And here are a few examples of what that might look like in actuality!

(Adapted with permission from Aurora Welcome Center: Refugee, Immigrant and Community Integration. Photos copyright @DiversifiED Consulting)

Teaching through Ramadan: Supporting our Muslim Students

Ramadan Mubarak! رمضان كريم

We’re in the season of Ramadan, which this year lasts from April 12 to May 12. (Updated 2024 dates: Sun, Mar 10 – Tue, Apr 9). This is the time of the year when many Muslims fast (or abstain from food and drink) from sunrise to sunset. It’s a time of both daily sacrifice and celebration. The holiday culminates in Eid, a several-day festival of food, gifts, and togetherness.

What is the Purpose of Ramadan?

Ramadan is a Muslim holiday. Islam, directly translated, means “peace”. Ramadan, which occurs during the ninth month of the lunar calendar, is a reflection of this. It is a period of introspection, prayer, self-improvement, and community.

Muslims believe that activities like fasting and zakat (charity and generosity) encourage self-discipline, gratitude, and empathy. Practicing these are qualities during Ramadan (and throughout the year) is said to strengthen one’s spiritual connection to God, or Allah (SWT). It is believed that the Qur’an was first revealed to the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) during the last ten days of Ramadan.

Who takes part in Ramadan?

Most Muslims celebrate the month of Ramadan, but not all participate in fasting. Those who are very young, elderly, pregnant, breastfeeding, menstruating, or have health conditions, might not fast. Some who do not fast during Ramadan may choose to recover missed days later in the year.

What does a day of Ramadan look like?

Suhoor begins a typical day during the month of Ramadan. This meal takes place before dawn, usually between 2-4 am, and is followed by morning prayers, or Fajr. If a person is fasting, they will probably return to sleep. Fasting has now begun, so the person will try to refrain from food or water until the Maghrib prayer at sunset.

Then, family and friends gather for Iftar. This is a celebratory meal that usually begins with the eating of dates to break the fast, followed by traditional dishes (and often in abundance!). Some families stay up late into the evenings celebrating, socializing, praying, or reading from the Qur’an.

Eid-al-Fitr marks the end of Ramadan. Morning prayer is followed by two or three days of communal celebration. During the time of Eid, families may decorate their homes with lanterns or lights, host elaborate meals, give and receive gifts, or attend street festivals dedicated to the occasion. It is an occasion of joy, gratitude, togetherness, eating, and giving.

How can I acknowledge and support my Ramadan-observing students?

Self-educate. Muslim students should not be expected to teach others about their faith, practices, or traditions. Do not assume that a Muslim student wishes to share about these experiences or explain a decision to (or not to) fast. By taking the time to learn more about the month of Ramadan and the folks who take part in it, we can identify points of connection and better anticipate students’ needs.

Avoid assumptions. Keep in mind that Islam, like any religion, is widely interpreted and experienced. Muslim families and individuals may enjoy varied traditions- including the degree to which they practice aspects of their deen, or faith. Talking to students or families privately about how to best support them can increase feelings of comfort and belonging.

Consider scheduling. Fasting from food and water can be tough on students. It can impact energy levels, concentration, and mood. Many students will wake in the hour before sunrise to eat and pray, so sleeping may be interrupted, too.

When planning for participation-heavy content, cooperative engagement, and deep-level thinking, try aiming for the morning, when energy and concentration are likely to be higher. Nagla Badir, writing for Teaching While Muslim, recommends having online assignments due late at night, so that students can complete them after they’ve had a chance to have dinner. This is also an opportunity to think carefully about the timing of calendar events like a band performance or prom, which can share time spaces with Iftar or Eid.

Badir also shares this calendar, where you can look up prayer times for students in your area!

Create safe spaces. For many observers, the period of Ramadan is a time of increased prayer, which occurs during specific windows of the day. Students who may have originated from countries or communities with high Muslim populations would have this time built into their school day. Of course, this is not often the case in U.S. schools, where many of the staff may not even be aware of this need. Having a space set aside (or two spaces, one for males and one for females) can help ensure that these students are seen and valued at school.

Muslim students who, for health or personal reasons, are not fasting during Ramadan may also benefit from a separate space during eating times. These individuals may face uncomfortable pressure or questioning as to why they are not fasting; having a safe location to go to can ease this stress.

Boost Socio-Emotional Learning. Ramadan is a time of family, friends, and community. Often, our observing students are physically distant from family members and/or feel that their holiday isn’t shared with others in the school or locality. This may be especially true for our Recent Arriver newcomers.

At school (whether in person or remote) we can be intentional about incorporating opportunities to learn and practice SEL skills- especially those that include elements of self-awareness, grounding, and collaboration. This important step can help diminish feelings of isolation and support students’ mental and emotional well-being during the period of Ramadan and beyond.

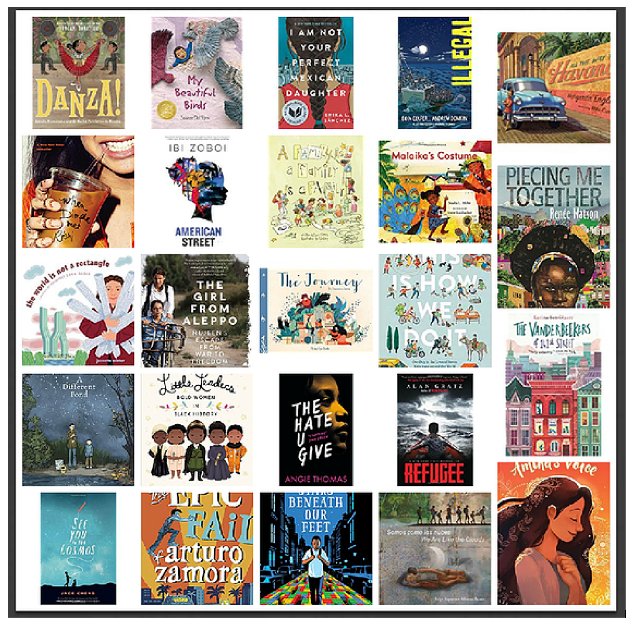

Engage through children’s books. Muslim and Muslim-American literature can be incredibly powerful in facilitating “door and window” experiences for Muslim students in the classroom. There’s an added benefit, too- books can engage non-Muslim students in ways that invite connection, empathy, and tolerance. We’ll visit some of these titles in an upcoming post. In the meantime, start here, at I’m Your Neighbor Books (I’d recommend sticking around to check out this super valuable sight!).

Where can I learn more?

Great question! Here are some of my favorite sites. Have more to add? Please do share them below!

Teaching While Muslim https://www.teachingwhilemuslim.org/

Hijabi Librarians https://hijabilibrarians.com/

ING- Ramadan Information Sheet https://ing.org/ramadan-information-sheet/

Learning For Justice: https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/teaching-about-ramadan-and-eid

Muslim Students Association National https://www.msanational.org/resources

With increased awareness- and with some tools in our toolboxes, we can be better prepared to support our Muslim students throughout this beautiful month and beyond, Inshallah!

Ramadan Mubarak, friends. Wishing you all you, peace, and abundance! لويز اليعفوري

Crossing Cultural Thresholds- Engaging EL Caretakers in the Trauma-Aware Conversation

Let’s look to tools and strategies that facilitate re-directive capacities and champion long-term moves toward resiliency. We’ll spend a bit of extra time focused on our Recent Arriver Emergent Lingual (RAEL) students. In this space, we’ll highlight EL parents and families as critical stakeholders in students’ trauma restoration processes.

Trauma-informed pedagogy relies upon, in part, the explicit teaching and modeling of regulatory and prosocial behaviors. Eventually, these strategies can be holistically embedded into children’s everyday school (and life) experiences. In the context of RAEL populations, this also means bridging cultural norms and expectations around mental wellbeing. As learning places, this requires a concentrated shift toward integrating diverse cultural value systems into our trauma-sensitive practice.

The National Council for Behavioral Health names two dimensions of sustainability in trauma-informed programming:

1. Making changes, gains, and accomplishments stick

2. Keeping the momentum moving forward for continuous quality improvement.

So, how can we best support these two dimensions? A sustainable path toward resilience requires us, as practitioners, to monitor students’ success and adapt our instructional cues as needed. Fortunately, we already recognize this as a best practices approach across all grade levels, content areas and language domains. We are experts at checking in on our students and personalizing the learning experience based upon individual strengths and needs. The same tenets apply to the processes of transition shock, including trauma.

Shifts are required in the broader educational landscape, too. Sustainability requires honest conversations about our organization’s infrastructure, including leadership, policies, and procedures as they ignite or diffuse underlying transition shock. It demands moving away from punitive practices and toward restorative solution seeking. Sustainability relies upon the collection and analysis of data in order to determine if our trauma-informed programming is effective and equitable. It means that all team members are equipped with tools for understanding and addressing student trauma, and that educators are widely supported in recognizing and managing the secondary stress that may arise through our work with trauma-impacted youth.

Essentially, we are charged with ensuring that the strategies we introduce are good fits for individual students. A good fit means that they are not re-triggering and are both culturally responsive and language adaptive. A good fit means that learners are empowered to experiment with mitigation strategies in their toolboxes, to fail forward in a safe space, to reevaluate without self-admonishment, and to try again.

Involving Caretakers as Critical Stakeholders

If we are to truly address transition shock (including trauma) in our learning spaces, then we must also become active in engineering webs of support around our students- in this case, we’re speaking specifically about our RAELs. Here, we’ll concentrate on arguably the most critical stakeholder group of all- the parents and caretakers of our Emergent Linguals.

In communicating with culturally and linguistically dynamic caretaker groups about transition shock, it’s important to first identify our guiding principles. How do we cross cultural thresholds to build authentic partnerships?

As with our students, safety and trust are paramount. Cultivate these properties as we would in the classroom- practice welcoming, routine, predictability, and transparency.

Be cognizant of biases around mental health and trauma. Name observed behaviors and avoid labeling.

Reduce isolation by connecting families to appropriate resources, as well as to families with socio-cultural commonalities.

Strive to meet with parents in person and, if needed, arrange for a trained translator wherever possible. Avoid using children as conversational brokers.

Talk to parents about the link between students’ school performance and socio-mental health. Use direct and clear language.

Remember that mental health terms may be unfamiliar, unmeaningful, or untranslatable for Recent Arriver parents. Translate these terms ahead of time if possible, and provide visual cues where appropriate.

Honor socio-cultural perspectives when advocating for student care.

Champion wrap-around supports and refer students for advanced care in a timely manner.

Sustainability is enhanced when students’ home and cultural values show up in the school space. Highlighting the voices of our RAELs’ caretakers can simultaneously bolster our culturally responsive efforts and temper student anxiety. Meanwhile, opening doors to culturally responsive communication around trauma-sensitive topics builds trust and enables a collaborative approach to long-term restoration.

Newcomer / Recent Arriver Classroom Reminders

We’re into the thick of the year. It’s a great place to pause and reflect on our practice so far this school year and how we will grow our students in the remainder of our time together. It’s a great time for Newcomer/Recent Arriver classroom reminders! Here, we’ll look at the non-negotiables.

What would you add? Be sure to share your thoughts below.

FOUNDATION

Classroom culture drives learning. Newcomer students thrive in classrooms that are safe, structured and predictable. In fact, predictability is a cornerstone of positive school engagement. Predictability breeds trust, trust lends itself to safety, and safety opens students up to entertain curiosity, absorb content and practice positive risk-taking in the classroom.

DIRECTION

It is important to lead with a plan and to ensure that the plan supports equitable participation for all students, including students who are new to the English language. Content–Language Objectives (CLOs) are an effective tool for creating a specific language focus (with the purpose of enhancing content accessibility for ELLs). They are widely flexible and can be implemented across all grades/subjects and for any number of ELs in a class. Content–Language Objectives guide lesson planning and ground student understanding throughout the lesson.

PLANNING

In preparing for English Language instruction, there is a tendency to over plan. When it comes to lesson planning, aim for relevance and quality, not quantity. Return to the Content-Language Objectives. Ask: 1. What one strategy will be most useful to my learners in making the key content more digestible? 2. What one strategy will my students use to demonstrate the language objective within the target language domain (reading, writing, speaking, listening)?

Can more than one strategy be implemented? Of course! Just be sure to aim for clarity. If things start feeling jumbled or unclear, return to your one original focus for each question. Our students will always perform better when they know exactly what is expected of them.

COMMUNICATION

It’s important to keep in mind the amount of fo language that students encounter in a given school day. Beyond the conversational language that must be learned to navigate the bus, playground or lunchroom, learners encounter languages within the language throughout the entire school day.

Let me explain. If conversational English (with its slang, reduced speech and media influences) is a tongue, so is the Language of Mathematics. Isosceles, divisor, and equation are not words students are likely to pick up in their informal conversations. This type of (academic) vocabulary must be explicitly taught. And if Math is a tongue, then so is the Language of Social Studies, the Language of Music, the Language of English Literature, and so on.

Our students encounter thousands of words in a day. For ELLs, this can be especially overwhelming. To reduce the language load, we can be intentional about listening to ourselves. How might we describe the rate and complexity of our speech? How can it be modified for clarity?

In short, here’s what we’re aiming for: Speech should be clear, deliberate and unrushed. (Side note: Louder or painfully elongated speech is not helpful.)

EXPRESSION

Language encompasses so much more than just vocabulary. Tone, register, slang, cultural cues, humor, sarcasm, reduced speech, body language, facial expressions, and gestures must all be negotiated in the context of learning a new spoken language. Gestures, or the motions and movements Gestures can be used to enforce an idea but should become less exaggerated with time, as understanding grows. Where possible, normalized conversational gestures are optimal.

PACING

ELLs often require a longer “wait-time” to produce a response. After questioning, allow up to two minutes of unprompted thinking time. If a student is not yet ready, offer cooperative opportunities for production. Partner-Pair-Share, Numbered Heads, or Rally Table are great approaches; and sentence starters can be embedded into any of these strategies. Just be sure that the student who was originally asked does, ultimately, have the opportunity to share his or her response with the class.

APPROACH

Labeling, visuals, realia, manipulatives, graphic organizers, sentence frames and hands-on exploration are essential to the ELL classroom experience. Each is a language-building path toward content accessibility. Additionally, we can be especially mindful that our curriculum and class reading materials reflect the diverse nature of our classrooms. Where do our students recognize themselves in the school day? How are students invited to express themselves using the four language domains?

PROCESS

Students, including English learners, should have guided agency over their own learning. Work with students to set goals, create viable paths toward these aims, and to monitor their success along the way. Cooperative structures are an important part of this process, as they encourage language development, enhance positive classroom culture and put students in the drivers’ seats of their own learning. Yes, our ELLs CAN meaningfully participate in student-led instruction and Project-Based Learning (PBL). Learn to establish supports… and then get out of the way!

CONSIDERATIONS

Newcomer students may be working through trauma, shock or other stressors. Monitor external stimuli to help mitigate significant stress. Learn to recognize symptoms and know when to ask for help. Work to recognize, celebrate and practice Socio-Emotional Learning (SEL) skills throughout the school day and school year. To build background on newcomer Trauma start HERE. For more tips on trauma-informed care for ELLs (and all students) take a peek at an RC article for Edutopia, found HERE.

INVITATION

You may be a child’s first teacher of their school career, their first teacher in America, or the first teacher to breakthrough. Smile. Show welcoming. Be an example of the possibility that exists for them.

Newcomer/RAEL Orientation Checklist

INDUCTION PROGRAMMING FOR NEWCOMERS & RECENT ARRIVERS

Induction programming is a best practices approach to Newcomer ESL/Recent Arriver English Learner (RAEL) education, as it acts as an essential framework for positive, integrated socio-academic participation. These processes are a means of orientating the student to his or her new school surroundings. As an added component, Newcomer/Recent Arriver learners are introduced to essential concepts and understandings that are critical to success in a school-specific environment. Guiding questions:

Who welcomes students and parents as they enter the school?

Who is the first school contact for Newcomer families? The second?

How are new students and parents introduced to the school and its staff? Are these processes amended when working with Newcomer families?

How are all students, including Newcomers, made to feel welcomed and safe at school?

What type of record-keeping systems ensures that no students are overlooked in the orientation process?

Orientation systems can be complex or straightforward. They can stem from the office staff; may include teachers, parents, and other students; or may originate at a Welcome Center site. We’ll focus our energies for this chapter on a few simple strategies that have a demonstrated effectiveness and are easy to implement. Then, if you’re interested in going further in developing your own orientation plan, I encourage you to visit the The Newcomer Student: An Educator’s Guide to Aid Transition.

PERSPECTIVE IS EVERYTHING

Did you ever have to move schools when you were younger? Or, what about that (huge) jump from the elementary grounds to the middle/high school campus? Overwhelming, right? I remember the first time I visited my high school as a soon-to-be-ninth-grader. I was so convinced that I would never be able to find my classes. Or my locker. Or my friends. I actually had nightmares about it.

And here’s the thing: I spoke English. I’d been in American schools my entire life and enjoyed a network of peers, all scheduled to endure the transition with me. Still, I was shaking in my boots.

For a moment, consider the experience of school transition from a Recent Arriver EL perspective. We’re not talking about moving across town, or even from another state. Imagine that nothing is the same. Nothing is predictable. Everything is lost in a cloud of newness: language, mannerisms, climate, clothing, school. How would you react in this situation? What would you most wish for? What actions could a school take to help to ease your anxiety?

Let’s first examine the most critical aspects of school orientation. As you read through the following checklist, some of items might seem erroneous. That’s common sense. Right- it’s common sense from our perspective, based on our own previous exposure to localized normative values. But “normal” isn’t normal everywhere.

Normal is a completely subjective concept.

And so, it is important to practice viewing our school and classrooms with raw eyes. We must remind ourselves that cultural misunderstandings are not a reflection of intelligence. They are a reflection of vast world experience- and that’s a really cool thing! When I find myself in a cultural cross-tangle with one of my students, I like to ask my class: “Can you imagine if I visited your country? Would I know how to do everything right away? Could I speak your language with your grandmother or cook sambusa as well as your father? Would I even be able to find my way to the market or to the school by myself?”

This usually garners some laughter and a hearty conversation about how I wouldn’t even know that I was supposed to bow or kiss three times instead of shaking hands. “Nooooo waayyy!” But, when I ask if they would help me to feel safe by teaching me the things I would need to know, my students all eagerly agree! Just taking a moment to recognize our students’ perspectives exposes our willingness to understand and relate to our students. This kind of effort can really break ground and lead to trust building.

Where can we anticipate questions, concerns or confusion? Here are some starters!

Download a printable Google Doc of the Newcomer Family Orientation Checklist HERE.

Newcomer Family Orientation Checklist

Logistics:

☐ Layout and map of the school

☐ School hours

☐ Student course schedule

☐ Meals at school (cafeteria options, subsidized meal applications)

☐ School transportation

School Contact Information:

☐ Location and phone number of the main office

☐ Attendance line contact, if different

☐ Names and locations of key administrative personnel

☐ Name, location and contact information of teacher(s)

☐ Name and location of key resource personnel: nurse, ELD teacher, counselor, etc.

Policies:

☐ Immunizations

☐ Attendance

☐ Dress code (including winter and gym attire)

☐ Homework

☐ Supplies

☐ Behavior & Discipline

☐ Health and Wellness

☐ Cell Phones

☐ Safety (Weapons, Smoking, Alcohol, Drugs)

☐ Field Trips

Student Participation:

☐ Co-ed learning expectations

☐ Sitting for long periods of time

☐ Carpet meetings/sitting on the floor (where applicable)

☐ Lining up as a class

☐ Raising hand to speak

☐ Lockers (where applicable)

☐ Bell policy and tardiness

☐ Bathroom and hand washing routines

☐ Independent and group work routines

School-based Events:

☐ Back-to-School Night

☐ Report Cards

☐ Parent Conferencing

☐ Concerts

☐ School dances

☐ International Night, if applicable

Student Engagement:

☐ Sports and Recreation

☐ After School Tutoring

☐ Summer School

Parent Engagement:

☐ Classroom volunteer opportunities

☐ Field trip volunteer opportunities

☐ Adult ESL

☐ Translation services

© The Newcomer Fieldbook, 2017

Understanding Student Identity: Diving into Race, Ethnicity and Culture

What constitutes identity? From one community to another, and from one school campus to another, we are likely to find widely varying explanations.

Conversations around identity are typically assigned bank of related vocabulary. Often, we employ these words – race, heritage, ethnicity, nationality, and culture- interchangeably.

This is problematic, and often muddles our concept of (and ability to recognize, embrace, and value) personal identity. It makes it easier to lump human distinctions into tidy categories based on a series of checkboxes. But the reality is, it’s just not that simple.

Race is vastly different than ethnicity, and heritage does not necessarily indicate culture. Fortunately, getting these concepts straight is not highly complicated, either. It just requires that we have a common working language. Let’s get to it.

First, let’s return to our vocabulary: Race, Ethnicity, Nationality, Heritage and Culture.

To organize these concepts in our heads, we can think of the elements as concentric circles. When I’m working with folks in a professional development setting, those pieces fit together like this:

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Let’s first look at the concept of “race” within the larger outside circle. Here’s the definition we’ll use for race: the composite perception and classification of an individual based upon physical appearance and assumed geographic ancestry; a mechanism used to facilitate social hierarchies.

Race, then, is an invented construct designed to enhance the social maneuverability of some and diminish that of others. If we look to our human history, we can see that the concept of race has been effective in achieving this aim. But the concept is overtly simplistic. Essentially, majority parties create arbitrary social categories that label those apart from them, and them fill in those categories with identifying descriptors for each category.

Race is also a malleable property. Racial categories (and their descriptors) differ from one society to another and change over time. They are susceptible to shifts in power, demographics, and socio-political climate. In the U.S., we’ve historically defined those race categories by color: black, brown, white, yellow and red.

Of course, we know that there must be so much more to the story than this.

The idea of ethnicity gets us a bit closer. We’ll describe ethnicity this way: An individual’s tie to a to a broader social group as defined by shared language and value systems, which may include nationality, heritage, and culture.

Ethnicity is a richer value than race. It captures the many elements that link a community of together. It also encompasses both past and present values of a social group. The most defining feature of ethnicity is that is self-definition. While one may be “born into” certain features of ethnicity, an individual may choose to abandon, adjust, or add to his or her ethnic identification.

The choice aspect of ethnicity also leaves room for ‘and’. Cherokee and Lakota. Latina and Korean. Palestinian and French. Igbo and Yoruba. Black American and white American. Multiethnic. Polyethnic.

This singular aspect of choice is what sets race and ethnicity apart. While both are inventive concepts, race exists only as an external social construct, placed upon an individual without choice. Ethnicity, meanwhile, exists as an internal construct with external influences and is marked by the mechanism of personal choice and affiliation.

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Nationality, heritage and culture may be viewed as separate from, but somewhat living under the umbrella of ethnicity. Language is also housed here. Language represents the means of interpersonal exchange between peoples of a country or community. It is also the conduit through which elements of ethnicity (including nationality, heritage and culture) are expressed.

Nationality refers to the country to which an individual was born, holds citizenship or identifies with as home. The element of choice is observable here. A student who was born in Russia but has lived in the United States since the age of six is likely to have a very Americanized world-view and may identify as American, even if her citizenship status does not reflect this.

The idea of heritage looks to the place or places from which one’s ancestors originated from and what those ancestors subscribed to. It is possible to identity with a heritage, but not the matching ethnicity. For example, a person may recognize his African descent, but identify as ethnically Afro-Caribbean. An individual may celebrate Irish heritage, but not speak the language or identify with customs linking it to that ethnicity.

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Finally, we arrive at culture. Culture, in many ways, is the most complex value. It is similar to ethnicity, but in a way, nested within it, as cultural indicators are part of the architecture of one’s ethnic identity.

Culture relates to the specific combinations of socially acquired ideas, arts, symbols and habits that make up an individual’s day-to-day existence and that influence his or her social exchange. So, ethnicity has to do with overarching themes that define a particular social group. Culture presents itself as (often material) markers of the ethnic group or its subgroups.

Culture has other attributes that set it apart from race, ethnicity, nationality and heritage. Namely, it is not determined by appearance. Culture is also a fluid property and is largely influenced by personal choice. Cultural behaviors may be changed, shared or acquired. Any person may pick up another’s culture at any time, and a person’s culture is highly likely to change over time, in whole or in part, based on new experiences, interests, and social influences.

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Often, the element of culture is further broken down into three layers: surface, conscious and collective unconscious. Zaretta Hammond, in her incredible work, refers to these areas as surface, shallow and deep culture. Surface culture mostly refers to observable markers: fashion, food, slang, art, holidays, literature, games and music. Conscious culture looks to the governing rules and norms of a community. It includes eye contact, concept of time, personal space, honesty, accepted emotions, and gender norms.

The collective unconscious culture is at the very core of one’s worldview. From this space, an individual processes the natural and social world- and also makes sense of his or her place within it. Spirituality, kinship, norms of completion, and the importance of group identity are all part of the collective unconscious.

It is also possible to have sub-cultures with our culture. For example, we may belong to a skateboard, cowboy, gaming or band culture. We can attach specific elements of action and expression to each unique social behavior/interest group.

Now we can step back and look at our map. When we put all of these elements together, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of what comprises an individual’s identity. We can move in the direction of looking past the first layer of race (and perhaps eventually remove this non-serving piece). We can, through culturally-responsive teaching practices, develop our expertise in peeling away layers in our students’ identities in order to explore the deep culture factors that truly drive belonging, motivation and learning.

Custom & Cultural Nuance in the Classroom Setting

Karen-Burmese family at International Night, Place Bridge Academy, Denver. May 2016. Photo: Louise El Yaafouri. The following is an excerpt from The Newcomer Student: An Educator’s Guide to Aid Transition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016).

EXAMINING CUSTOM & CULTURAL NUANCES

Authentic cultural tolerance and understanding is a fundamental basis for success in the Newcomer classroom. A willingness to maintain awareness and open-mindedness in culturally divergent settings can promote positive exchange and individual growth. When we are able to engage with our students from bases of respect, tolerance, and attempted understanding, we also foster reciprocation of these same traits back onto ourselves, and also toward classroom peers. If, on the other hand, we develop habits of projecting fear, misinterpretation, and bias onto our pupils, then we have also contaminated the entire sanctity of the learning environment.

We know that the ways in which we view and interact with our students can tremendously influence students’ classroom and learning success. With regard to tolerance and cultural respect, every lesson begins with ourselves. Our behaviors will be modeled long before, and long after, our words have an opportunity to make an impression.

Realistically, however, and despite our best efforts, it can still be difficult, confusing, or unsettling to come into contact with cultural tendencies that are unfamiliar to us. For example, acceptable distances of physical proximity, vocal volume norms, pleasantry tactics and privacy stipulations can dramatically swing from one cultural demographic to another. It is impossible to notice and make sense of all of our students’ culturally divergent tendencies.

We will face many challenges in recognizing, interpreting, and accepting our students’ many cultural qualities. No one approach to living or learning necessarily trumps another. Each is simply different. Indeed, our Newcomer students may prove among the richest, most experienced cultural guides that we will know.

In the end, it is not a student’s sole responsibility to change to suit the teacher’s needs. Unquestionably, our Newcomers will be required to learn and adopt many westernized customs in order to successfully integrate into our culture. As educators, we can also allow ourselves some room for adjustment. These small personal transformations are reflected in the positive and tolerant ways that we choose to interact with students and plan for their optimal learning in each school day.

EYE CONTACT

One specific conundrum is the eye contact issue. In the Newcomer setting, it is very common to encounter students who stoutly refuse to look an adult in the eye when they are being spoken to. This behavior may be especially evident if a child is being pointed out or reprimanded. In the West, direct eye contact with an adult or elder is typically equated with respect and obedience. Therefore, a dismissive look signals defiance and disinterest. This is our truth.

However, direct eye contact between a child and an adult is considered atypical behavior in many of the world’s cultures. Throughout East and North Africa, for example, direct eye contact between a child and elder is considered a sign of intense disrespect on the part of the youth. Resettled persons from these regions will very likely instruct their own children to look down when speaking to anyone older or of greater perceived importance, as this is what is considered the honorable thing to do.

Aha! Our eye contact-avoiding students, whom we may have perceived as acting disrespectfully, have been demonstrating utmost respect all along. These individuals exhibit respect via their truths, and according to personal experiences and relative social norms. There you have it. The teacher is just not always right.

LOSING FACE

Other cultural nuances are also evidenced in the classroom. For instance, many East Asian and Arab students are noticeably consumed with the notion of losing face. That is, they strive to avoid even the slightest run-in with public humiliation, especially that which would bring shame to the greater family unit.

This phenomenon surrounding fear of failure typically prevents risk taking, volunteering, and sometimes even trying in the classroom. Educators who come from a background of outspoken Western idealism may experience frustration at recurrent student episodes of superfluous caution. We might expect or wish that our learners would simply take a chance; to speak out, speak up, and care just a little less about peer judgment and evaluation.

From a culturally mindful perspective, meanwhile, we see that for most Newcomers, family and community comprise the very heart of a meaningful life. To embarrass or shame the family name could result in shunning either of the individual by the family, or the family by the community. Both fates equate to social death. Excellence and recognition, on the other hand, can bring respect and glory to an entire family and community.

In terms of social cohesiveness and support in the post-resettlement con- text, there are certain advantages to the saving face mentality. This inherent code of honor serves as a binding agent for resettled ethnic populations -and it may also serve as a cohesive strand between culturally diverse ethnic populations.

In the classroom, students who had been taught to adhere to saving face principals are very frequently self-driven learners who diligently applied themselves to their studies in an extended effort to bring happiness and honor to the home. They are likely to hesitate in answering questions, unless they can be absolutely certain that they have the correct response, and they may strive to please the teacher in every possible way. We can guide these students toward classroom chance taking by providing a nurturing classroom environment and celebrating mistakes as opportunities for continued growth.

LEFT HAND AS ABOMINATION

In many non-westernized cultures, the use of the left hand is considered unclean and is strictly avoided in any social setting. Eating, passing objects, hand holding, patting, or greeting with the left hand may be considered taboo.

It is wise to be cognizant of this when presenting children or parents with pencils, paper, or treats with the left hand; the act may be received as inauspicious or as an outright abomination. Also, children who may be naturally left-handed go to great lengths to avoid using this hand for writing or other activities in the classroom, and quality of work may be impacted as a result.

ASKING FOR AID

Asking for help is not encouraged in most East Asian school settings. This may occur for several reasons. The first has to do with the concept of saving face, in which an individual may feel personal shame or greater family shame for not understanding. Second, asking questions often denotes individualism, which is rarely a prized value in Eastern cultures. Finally, in many countries, the teacher is considered the expert and authority in all matters relating to education, and therefore, it may be perceived as disrespectful to ask a teacher for clarification on a subject. As a potential result of heritage customs, the concept of asking for aid may require explicit modeling in the host setting.

WANDER-AND-EXPLORE TENDENCIES

Many cultures place great emphasis on the need for children to learn through exploration and experience. Even the very young are encouraged to experiment, play, and seek answers in a very tangible sense, often apart from direct adult supervision. In some communities, practical education is regarded with as much or more reverence than structured book learning. The tools, ingenuity, and skill sets that children gather during this adventurous time often enable future work and survival success, thus serving as an asset to the community as a whole.4

This is in direct conflict with traditional Western Sit-Up-Straight-And-Tall methodology. As a result, students who are more accustomed to wander- and-explore learning may have a very challenging time adjusting to certain classroom norms in the host setting. We’re talking about that child who seems entirely allergic to a desk chair. The one who stands as he or she writes, whose shoes have a habit of magically evading his or her actual feet, and whose desk is a nesting place for pen caps, twigs, puffballs, marbles, and origami triangles—that just might be your Wander-And-Explore student.

And it’s ok. These students are still learning, after all! Typically, these harmless classroom behaviors will dissipate with time. Again, they are not wrong; they are just different than what we have been trained to be used to. Best practices call for us to provide explicit learning opportunities for wander-and-explore learners that accentuate their problem-solving strengths, such as manipulative learning techniques. Meanwhile, we can promote positive behaviors that will lend to their future success in westernized schooling environments.

PERSONAL SPACE AND PRIVACY CONSIDERATIONS

In many countries and cultures, personal space is not valued as a commodity. In these settings, spatial boundaries may be nonexistent. It will be very natural for students from these regions to position themselves extremely close to other individuals throughout the school day. Custom may encourage students to push right up to another student while standing in line, or think little of physical contact such as touching elbows or knees at a desk. Talking may occur at close range.

These behaviors are a routine part of life in many African and Middle Eastern countries. They are, in their essence, innocent reflections of human nature, in contexts where many people share a limited space. However, privacy considerations can become problematic in the classroom when someone with contrasting personal space values encounters them. Spatial consideration may require explicit teaching and modeling within the classroom.

ADHERENCE TO TIME

Time is not regarded with the same level of importance in all parts of the world. In the westernized sense, timeliness is considered a virtue, and adherence to time is the common norm. In many cultures, however, timeliness may be out-valued by social interaction and other obligations.

In most African countries and many regions of East Asia and Central and South America, for example, it is considered extremely rude to cut greetings or exchanges short in an effort to make an appointment deadline, or for any other reason. Thus, meetings and other professional or social engagements can run far behind schedule. Lateness, in most cases, is not considered rude or irresponsible. Loose adherence to time is merely a reflection of cultural values. Therefore, punctual behavior may need to be overtly encouraged in the Western setting.

VOLUME AND TONE

Normative values for conversational volume can vary drastically between cultures. Vocal registers that may be customary to many Middle Eastern or African cultures may feel harsh or alarming, at least according to Western expectations. In many regions, verbal exchange is an animated and lively process, and volume considerations may not be as esteemed as they are in the host setting. Meanwhile, Latin American or East Asian volume norms may be seem diminutive in contrast to host values, as soft speech and inwardness are considered virtuous character traits. In the classroom context, we need to work with our learners in establishing volume norms that are conducive to social and learning success.

UNIFORMITY

Individualism is a trend that is largely exclusive to Western cultures. Most other countries celebrate collectivism, which encourages viewing the self as inherently and wholly linked to surrounding bands of community, beginning with the family. This whole-group perspective serves to motivate decision making that will positively influence not only the self, but also the entire social dynamic.

Learners who are accustomed to uniformity value systems may find little appeal in standing out in the classroom setting. They may have limited desire to be the best, or to ask for help or clarification. Blending into the overall group dynamic is seen as a definitive honor and benefit to the family and cultural group.

We can guide our students and families to enjoy some of the benefits that individualism can provide in the new environment. Ultimately, we hope for a balance. Students will need to exercise some elements of independence in order to fully thrive in the twenty-first-century learning environment; and they may also be compelled to retain certain heritage values. We can do our best as educators by honoring both avenues, as well as all the gray areas in between!

TEACHER AS EXPERT

In most non-Western cultures, educators are highly regarded as essential pillars of the community. The teacher, in these societies, is considered a sole authority in terms of all learners’ academic welfare. Thus, education is considered the singular responsibility of the teacher. As a matter of trust and respect, parents are socially deterred from interfering with this process. Newcomer parents who are accustomed to this scenario will be highly unlikely to question the role or actions of a teacher, as such infringements would be considered offensive and disrespectful.

Complications occur when this behavior, as viewed in the West, may resemble a “lack” of parental involvement or disinterest in a child’s learning. We may become frustrated or affronted. However, the families themselves probably believe they are doing the right thing. Indeed, the concept of parent involvement in education is almost exclusively a North American one.

In effort to counter this, and other misconceptions, we must share in the responsibility of opening healthy lines of communication between the home and the school. In doing so, we make room for understanding, cooperation, and collaboration. When we, as host educators, are better informed, we’re less likely to react out of confusion or insult. Instead, we might be more inclined to respond with compassion, understanding, and careful planning.

By cultivating our own mindfulness of the cultural distinctions that exist in our classrooms and schools, we can enjoy more meaningful and impacting relationships with our students and their families. As a holistic outcome of cultural tolerance, trust can be established. From a place of trust, we can wholly access our students’ learning capabilities. This is the place where magic happens.

Sources:

Virtue, David C. (2009). Serving the Needs of Immigrant and Refugee Adolescents. Principal, VA. Vol. 89, No. 1, 64–65 S/O

Moore, Dennis (2004). Conceptual Policy Issues. In R. Hamilton & D. Moore (Eds.), Educational Interventions for Refugee Children (p. 93). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Loewen, Shawn (2004). Second Language Concerns for Refugee Children. In R. Hamilton & D. Moore (Eds.), Educational Interventions for Refugee Children (pp. 35–52). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Charny, Joel (2008). World Refugee Day: Where are the World’s Hidden Refugees? Refugees International. Located at www.refugeesinternational.org/blog/world- refugee-day-where-are-the-worlds-hidden-refugees. Retrieved Feb. 2014.

Meyer, Erin (2014). The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Bound- aries of Global Business. PublicAffairs Publishing.

Morrison, Terry & Wayne A. Conaway (2006). Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands, Adams Media.

Lustig, Myron W. & Jolene Koester (2009). International Competence: Interpersonal Communication Across Cultures (6th Edition). Pearson Publishing.

Lewis, Richard D. (2005). When Cultures Collide: Leading Across Cultures (3rd Edition). Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Storti, Craig (2007). The Art of Crossing Cultures (2nd Edition). International Press.

Refugee 101, Part 2: Who is a Refugee?

Image is part of a learning video created by Louise El Yaafouri for Colorado Refugee Connect. View the full video and get involved at corefugeeconnect.org.

Currently, there are more than 65 million displaced persons in the world. Of those, nearly 26 million are classified as refugees. More than half of the world’s refugees are children.

Less than half of one percent of the world’s refugees will ever be resettled to a third party country, such as the U.S. A slight handful of that exceptional one percent will make their way into our schools and classrooms. This means that our newcomer students truly are one in a million- and in the broader context of displaced persons, closer to one in a billion.

As educators, we may be presented with the unique opportunity- and awesome responsibility- to serve students from refugee backgrounds. In this five-part series, we’ll explore the refugee experience, outline pre and post-resettlement processes, and celebrate resettled refugees as assets to our communities.

WHO IS A REFFUGEE?

Migration is a central theme of the human story. Many, including including immigrants and migrants (by technical definition), relocate by choice- usually in search of new opportunities or improved ways of life.

Others are forced to relocate as a means of survival. Displaced individuals are pushed from their homes or communities involuntarily and under high duress- often leaving behind possessions, loved ones and personal histories. Catalysts for displacement include war, famine, natural disaster or economic instability.

Refugees are set apart from other displaced populations by one critical feature. The flight of a refugee must be related to war or violence, and they must experience an earnest fear for their life as a result of ongoing persecution.

This comes from the 1951 Geneva Convention, the outcome of which defines a refugee as one who fled his or her own country because of persecution, or a well-founded fear of persecution, based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. Asylum seekers meet the criteria of a refugee but are already living in the host country or are seeking asylum at a port of entry.

Image is part of a learning video created by Louise El Yaafouri for Colorado Refugee Connect. View the full video and get involved at corefugeeconnect.org.

Each story of the refugee experience is unique. Some travel through multiple countries in search of asylum. In the process of escape, many must tolerate uncertainty or entrust their lives to smugglers. Some endure periods without food, water or shelter. Many flee without important documentation. Some are forced to leave loved ones behind.

The majority of refugees relocate to urban camps, where groups of affected individuals band together within established cities. Urban camps are generally makeshift and may evolve to have their own economies. Some resettle in formal refugees camps, typically organized and operated by the UNHCR. These are the image of refuge camps that most Westerners are familiar with, usually having standardized tent structures and organizational staff.

From The Newcomer Student:

It is difficult to capture the essence and extent of what a refugee camp actually is. Refugee settlements are not typically self-supporting, and rely extensively on external aid for nearly all matters of finance, food, health, and viability. They are notoriously unglamorous, routinely undersupplied, and statistically dangerous. The UN High Commission for Refugees offers that, “Refugee camp is a term used to describe human settlements which vary greatly in size and character. In general, refugee camps are enclosed areas, restricted to refugees and those assisting them, where protection and assistance is provided until it is safe for the refugees to return to their home or to be resettled elsewhere.”

On average, a refugee lives in a camp setting for 17 years. It is common for refugees from one country to be born in a refugee camp in another country (for example, a Bhutanese student may identify as Nepali, a Burmese as Thai, or a Congolese as Tanzanian.) On average, a refugee is away from the heritage country for 20 years before a return can be realized.

Prior to upheaval, most refugees did not desire to leave their home countries. In fact, this process can be very traumatic. In her poem “Home” Somali poet Warsan Shire writes, “No one leaves their home unless their home is the mouth of a shark.”

SOURCES:

American Immigration Council (2013). Located at americanimmgrationcouncil.org. Retrieved Oct. 2012.

Russell, Sharon Stanton (2002). Refugees: Risks and Challenges Worldwide. Migration Policy Institute, 1946–4037.

Hamilton, Richards & Moore, Dennis (2004). Education of Refugee Children: Documenting and Implementing Change. In Educational Interventions for Refugee Children, eds Richard Hamilton & Dennis Moore, London UK: RoutledgeFalmer, Chapter 8.

McBrien,J.Lynn(2003).A Second Chance for Refugee Students. Educational Leadership, Vol. 61, No. 2, 76–9 O. Educational Needs and Barriers for Refugee Students in the United States: A Review of Literature. Review of Educational Research Vol. 75, No. 3, 329–64.

United Nations, High Commissioner for Refugees (2012). United Nations Communications and Public Information Service, Geneva, Switzerland. Located at unhcr.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

Patrick, Erin (2004). The U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program. Migration Policy Institute, Washington, D.C. Located at migrationpolicy.org/article/us-refugee- resettlement-program. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

United Nations Convention related to the Status of Refugees (1951). UN Article 1. Located at unhcr.org. Retrieved June 2011.

International Refugee Committee (2015). SOAR, New York. Located at rescue. org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

Van Hahn, Nguyen (2002). Annual Report to Congress- Executive Summary. Office of Refugee Resettlement. Located at acf.hhs.gov. Retrieved Dec. 2010.

Edwards, James R. Jr. (2012). Religious Agencies and Refugee Resettlement. Center for Immigration Studies. Memorandum, March 2012.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2012). United Nations Communications and Public Information Service, Geneva, Switzerland. Located at unhcr.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

U.S. Committee for Refugees & Immigrants (USCRI) (2015). Arlington, Va., refugees.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

U.S. Committee for Refugees & Immigrants (USCRI) (2015). Arlington, Va., refugees.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) (2013). Path to Citizenship. Located at uscis.gov. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

U.S. Committee for Refugees & Immigrants (USCRI) (2015). Arlington, Va. Located at refugees.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) (2013). Path to Citizenship. Located at uscis.gov. Retrieved Aug. 2014.

Refugee 101, Part 1: An Introduction

The only remaining photo of Eh Doh Htoo and his family in the Thai refugee camp for Karen Burmese. He shared this photo with our class as part of a “Heritage Book” project in 2009. He graduated high school last year.

The following is an excerpt from The Newcomer Student: An Educator’s Guide to Aid Transition by Louise El Yaafouri (Kreuzer), available HERE.

An Introduction to the Refugee 101 Series

Newcomer students are often defined by a long and complicated series of statistics: data scores, influx patterns, poverty analyses, and of course, school performance grades. Certain figures are certainly useful and valid. But they lead us apart from the relatable, tangible person. The relatable, tangible student; the learner we show up for. This leads us to the who.

In elementary talk, human seeking refuge is the main idea of the refugee story. Refugees are individuals with palpable faces and names who are colored by real life stories, experiences, families, and successes. Refugees and immigrants, not apart from our host-nation selves, are people—parents, children, adventurers, workers, dreamers, teachers, students, feelers, believers, doers, and learners.

Again, like us, refugee individuals and families carry with them other things: tribulations, stressors, and personal legacies. Some family fabrics are cohesive; others show wear. Some individuals appear well adjusted and decodable, while others are stalemated in secrets, burdens, and internalized fears.

These pieces, combined, highlight one simple, beautiful, extraordinary truth. We are all human. Each of us is susceptible, and yet, each of us is a channel for resiliency. We are all magnificent and full of promise, just as we are tarnished and unsteady. Each of us owns an access point to greatness. More than this, we all possess the inherent ability to help and guide one another through processes of personal and contextual transformation.

Let’s think this through. Are we, as westernized Americans in our own subjective neighborhoods, so exempt from characteristics of trial, loss, joy, confusion, relocation, or overcoming? Of course not! Sure, some of our stories register relatively low on the scale of global severity. Nevertheless, our personal tribulations and successes are meaningful to us, within the context and perimeters of life as we are familiar with it. No story is insignificant.

Greatness belongs to each of us.

"Home": Acknowledging the Complex Transitions of Refugee Newcomers

Drawing by former student Pah Leh Paw (age 9), depicting the Thai refugee camp where she grew up, after her family fled from the Karen cultural region of Myanmar Burma.

“I AM FROM . . .”

In my first year of teaching in the Newcomer sector, I remember feeling flabbergasted by one very real truth: our little four-walled classroom housed the world inside its perimeter. Out of the twenty-five students that first year, fourteen countries were represented in our classroom, with nineteen first languages among them. I still cherish this memory, and perhaps more so now that I’ve also acquired some understanding of the unique countries, customs, and languages that we have in our care.

I arrived as head of the classroom that year, the first year that our refugee-magnate school was set in motion, highly unprepared. I was fresh, sure, and knowledgeable in the field of education, too. I was also remarkably naïve. Armed with personal monologues of out-of-country experiences, I thought I was worldly, exposed, and ready. Then, I got schooled by a class of eight-year-olds.

When, for example, students stated, “I am from Burma,” I assumed, well, Burma. As in, one Burma, the one I located on Google Maps (just to refresh my memory . . . of course). As in, one culture, one language, one struggle, one united journey to our classroom.

That episode of simplistic thinking was short-lived. Within days, I figured out that several of my Burmese students couldn’t actually communicate orally with each other. Moreover, this group of students did not always appear outwardly friendly toward one another, despite their apparent cultural similarities. In fact, I was noticing intense tensions and aggressions between like-cultured groups, even while cross-cultural communications remained friendly and outgoing.

At one point early in the year, Snay Doh came to see me in private. He asked to move his seat away from his Thai peer, Thaw Eh Htoo. He wished to sit at a separate desk, between Valentin from Burundi, and Khaled from Yemen. “I don’t mind thinking about this, Snay Doh,” I replied, “but I hope that you can explain to me why this is a good idea. Moving your seat isn’t going to make a bigger problem go away. What is it that seems to be keeping you and Thaw from getting along?”

Snay Doh, with his limited English vocabulary, broke down the entire dilemma, with Crayola illustrations and all. In the end, I learned that Snay Doh’s parents were Burma-Burmese, and that he was born in the refugee camps in Thailand. Thaw Eh Htoo was also born in a Thai refugee camp. However, his parents were Karen Burmese. Not only were these two families from geographically, linguistically, and culturally separate parts of Burma; they were also at war with one another.

With a little more research, I came to realize that four rivers physically separate the small nation of Burma into five distinct geographical regions. Within these regions, a multitude of individual tribes maintain separate and exclusive lifestyles and cultures. Seven of these tribes demand high social and political prominence. These clans have an epic history of interaction, often involving warfare on every level and for every reason: territory, religion, water, trade, and government.

Members from five of these tribes held places on that first year roster. So, no; that original seating arrangement with four of those Burmese students, of four separate religions, customs and dialects at the same table didn’t work out so well. (Enter school-wide positive behavior system roll-out.)

Similar dichotomies are repeated each year in our schools and classrooms, and are reflected in the lives of our students from all over the world: Congo, Iran, Somalia, and Libya, and many others. The truth is that people who originate from one country are not necessarily homogeneous, or for that matter, oozing with camaraderie with one another. Fundamental views and values may vary dramatically, even to the point of enmity. For me, this lesson was critical. Indeed, we are never done learning.

AS THE CROW FLIES

Interestingly, our students’ documented countries of origination are rarely aligned with actual ancestral roots. This occurs primarily because many of our students are transported to (or even born in refugee camps) proximal to the heritage region.

For example, most Nepali refugees are Bhutanese. Many Thai students are Burmese. Our Kenyan students might be exclusively Congolese, Somalian, Rwandan, or Ethiopian. A Lebanese student’s first home may have been Syria, Palestine or Afghanistan.

Sometimes a spade is a spade; Congo really does mean Congo, and there is no need to complicate things further. But often, it doesn’t hurt to engage in a little sleuthing. The results can be astonishing. Frequently, Newcomers will have lived in a multitude of nations, even leading up to the country of origin that appears on resettlement documentation. This information can be helpful, in that it allows for additional insights into students’ probable cultural and learning backgrounds. It might also sway us away from topical assumptions and approaches to our craft. Cultural geography 101, via the wide-eyed testimonies of our learners.

The list below indicates possible refugee origination locales. The perimeter countries represent heavily documented home nations. The adjacent regions are plausible induction zones. Often, grouped nations may be interchanged as first, second, or third origination countries. Of course, this resource equates to a rough-sketch approximation guide. The only true authorities on our students’ pre-resettlement paths are our students and families themselves.

POTENTIAL REFUGEE ORIGINATION LOCALES

Nepal: Bhutan, Tibet

India: Iran, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, and China

Kenya: Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Somalia, Sudan, and Ethiopia

Ghana: Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Liberia, Togo, Benin, Mali, Nigeria, and Senegal

Egypt: Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Libya, Syria, Djibouti, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Yemen, Congo, and Lebanon

Libya: Tunisia, Lebanon, Syria, Eritrea, Sudan, Senegal, Egypt, Somalia, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo, Yemen, Djibouti, and Algeria

Thailand, Malaysia: Myanmar Burma, Karen Burma, Chin Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and China

Bangladesh: Rohingya Burma, Urdu Pakistan, Iran, Philippines, and Vietnam Jordan: Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Armenia, Bosnia, Serbia, and Afghanistan

Turkey: Russia, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan

Brazil: Venezuela, Honduras, Paraguay, Ecuador, Columbia, and Costa Rica

Mexico: Costa Rica, Guatemala, Haiti, Jamaica, Columbia, Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Honduras, and Chili.

8 Ways to Optimize a Learning Culture... and Celebrate Diversity

Culture. It’s the latest education buzzword to catch fire, and it is applied to a seemingly endless range of affairs. We refer to our students’ heritage cultures. We toss around the idea of a school culture, a classroom culture, a staff culture. So, what exactly are we talking about here? In the simplest possible terms, we can look at it in this way:

“Culture is the way you think, act and interact.” –Anonymous

From this lens, it is indeed possible to reference "culture" across such a variety of social platforms. How our students think, act and interact at home and in their communities is a reflection of their heritage culture. How we think, act and interact at work is a reflection of our work culture.

Let’s consider our schools and classrooms from this same vantage. Looking to the best versions of ourselves and our programs, what do we envision as an optimal learning culture for our students and staff? How are we encouraged to think, act and interact with our students and colleagues? How are we teaching learners to engage with each other in affirmative ways?

As a school or classroom leader, these are important thoughts to map out. My ideas may not look the same as your ideas. That’s ok. We can lay some common ground, though. The following cues present an opportunity to check in with your own vision of school culture. How can you help to improve the way that your team thinks, acts and interacts?

1. Invest in Students

We all ache to know that someone we care about is standing firmly behind or beside us. If our aim is to increase a student's success rate, our honest investment in both their present capacity and future potential is non-negotiable.

Express a genuine interest in each individual. Learn how to pronounce student’s names correctly and begin using them on the very first day. Ask questions about students’ heritage culture and allow for safe opportunities to share these insights with other classmates. Offer relevant multicultural reading materials. Post flags or maps, and have students mark their heritage country. Be a listener. Find out what students find interesting. Commit to supporting students with time-in over time-out. Show up. Keep promises. Practice being present and mindful with students. Nurture connectivity.

2. Provide Choice

When presented with choice-making opportunities in a safe, predictable environment, learners develop self-efficacy and strategizing abilities. We can scaffold these processes to enable students to grow as wise decision makers. Begin by limiting the range of available options. Model reasoning through active think-alouds.

Also, it is important to allow time for students to consider and process potential gains and sacrifices involved when choosing between items or activities. Similarly, prompt students to predict the probable consequences of unwise choice making and to reflect on these outcomes when they occur. Incorporate choice making throughout the day. Station (center) activities, choice of paper color, homework, reading book, order of task completion and game selection are manageable places to start.

When students are invited to make healthy choices- and have opportunities to practice doing so- they are much more inclined to become invested, engaged learners.

3. Provide Clarity

Students, not unlike adults, desire to know what is expected of them. Who doesn't enjoy a road map to success? By sharing bite-sized road maps with your students throughout a school day or school year, you are helping them to succeed. “Bite-size” can be defined as 3-5 clear steps, with a target of three.

As we’ve already mentioned, clarified expectations foster routine, predictability and ultimately, a sense of safety. Be sure that instructional objectives are posted and communicated. Is your class schedule visible and correct? Do you refer to it throughout the day? Are station areas and supplies labeled (using rebus indicators, where necessary)? How often do you review key routines? Check your day for clarity. Define and refine.

4. Trust

Trust that students are wholly capable of making great choices and doing the right thing. Does that mean perfection? No. It does mean that in a healthy, facilitative environment most students, most of the time, will strive to meet the expectations set by (and modeled by) the teacher. We are intentional about setting the bar high, because that’s where students will reach. Maintain confidence that they will stretch to achieve it.

As students see that you trust them, they will begin living up to the expectation that they are probably doing the right thing. They will almost always respond by trusting you in return. Aim for autonomy. Give away power (when appropriate). Expect greatness.

5. Practice Problem Solving

Investigation that relies upon solution seeking engages students in developing deeper concept understanding and creative thinking abilities, while also building essential life skills. Problem-solving behaviors are learned. They are either explicitly taught or modeled by others. The school is an ideal incubator for nurturing these attributes.

Offer specific steps toward solving a problem. Model these thoughts and behavior patterns. Provide multiple opportunities for students to practice problem solving in a variety of subjects and contexts. View problems as “puzzles”. Solution seeking is a willed behavior. Our role is to guide the discovery of enjoyment and creative thinking in these processes.

6. Teach Critical Social Skills