TIII Back-to-School Series: Visual Orientation Handbook

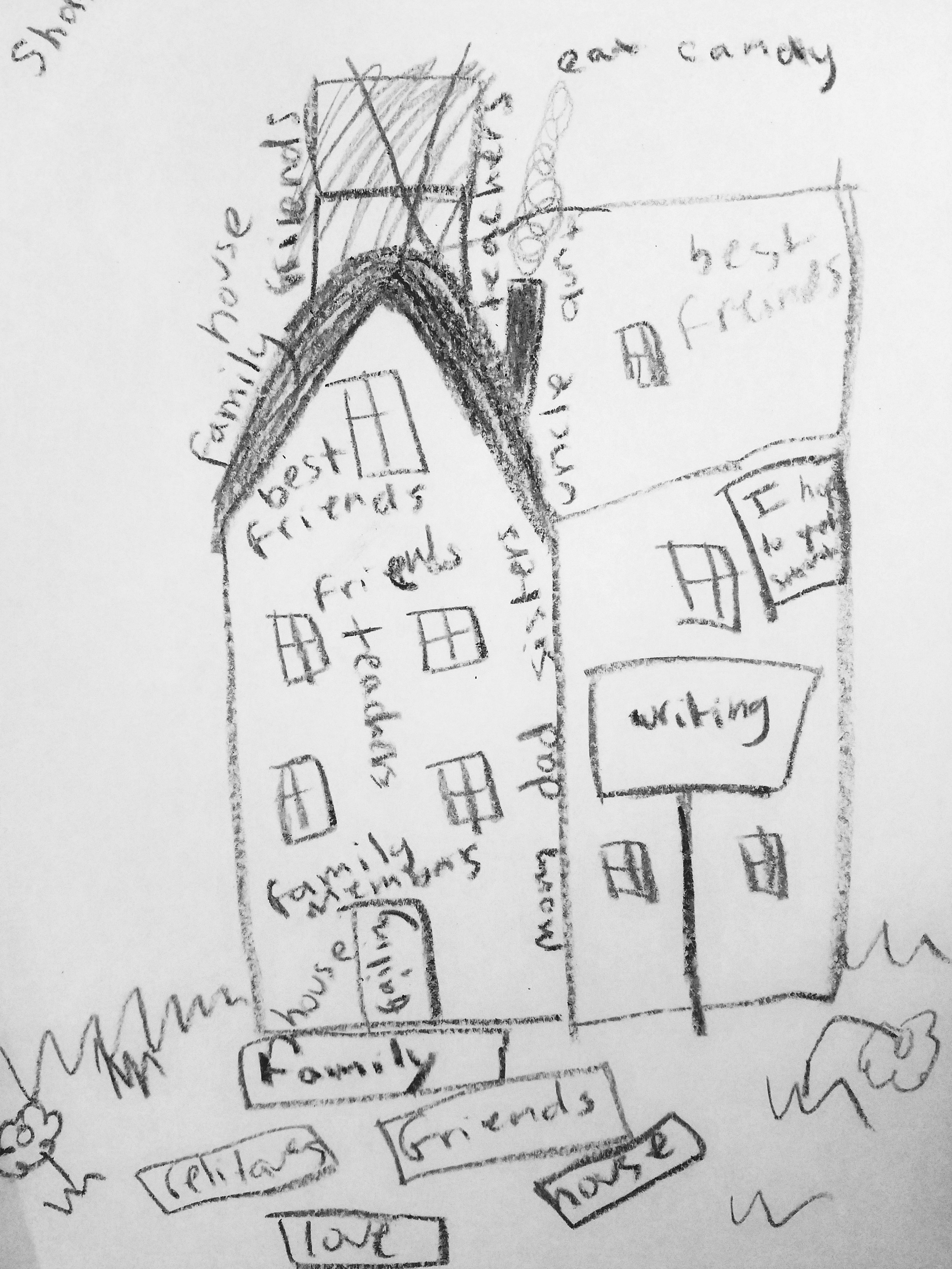

I absolutely love this idea of a visual orientation handbook, shared with me by Silvia Tamminen, coordinator at the Aurora Public Schools (APS) Welcome Center in the Denver suburb of Aurora, Colorado.

The Aurora Public Schools (APS) Welcome Center supports one of the most diverse student populations in the country. This demographic includes a large number of folks resettled refugee status. The district is now home to students from all over the world, with especially robust cultural representation from Bhutan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Libya, Syria, Myanmar, Côte d’ Ivoire, and Eritrea.

Families with school-aged children who are new to the district and also new to the English language are directly referred to the APS Welcome Center. Staff guide Newcomer families through the processes of student registration and school orientation.

Sylvia Timmenem heads this effort. She’s a human rights professional with a concentration on refugee and migration issues. Her knowledge of policy and practice is evident. But she’s also approachable and down-to-earth, with a bold, welcoming smile. As I glance through her workspace, I notice elements of her Fin culture.

“Immigration is something I share with our clients,” she tells me. But she’s also quick to point out that while there are some parallels, her path to America was smoother than many of those she sees in her day-to-day work. Sylvia is deeply aware of the privilege that comes with choice, with a previous knowledge of the English language, and even her appearance. Nonetheless, she does have an understanding of just how complex and overwhelming the immgration process can be. This awareness adds an additional layer of humanity to her interactions.

Sylivia came on board with the APS Welcome Center program in its inaugural season. She and her team built the organization from the bones up. The visual orientation handbook is among the group’s creative, solution-seeking efforts.

The handbook is a non-consumable resource with a permanent home in Sylvia’s office. It is composed of full-page photos and illustrations, slid into sheet protectors and organized into a three-ring binder. Each image is captioned with a simple explanation, which is (or can be) easily translated into a preferred language. Sylvia or another APS staff member reads the book alongside incoming families (and a translator, if requested). Page by page, the tool lays out the expectations for a typical school day.

For example, one picture shows a group of students sitting on the ground listening to a read-aloud. The caption reads, “Sometimes, students sit on the carpet during the school day.”

This was an important inclusion, Sylvia assured me. “Many times our parents cannot believe that their child would sit on the floor to learn anything. In some of their own countries, that would be very strange and maybe make a parent very angry.” She points out that often these seemingly “everyday” aspects of the school day can be overlooked. But in the context of welcoming families from culturally diverse backgrounds, taking the time to explicitly detail various aspects of the school experience can go a long way.

Here are some other situations included in the APS visual orientation handbook:

Kids receiving lunch on a tray (many recently arrived learners would have gone home for lunch or packed their own meal)

Young adults putting their supplies in lockers (this may be a first-time experience for many)

Students arriving for school at or before the scheduled time (concepts of time and urgency around timeliness varies greatly from one culture and context to another)

Photos of co-ed teaching staff (learners and their families may have culturally influenced expectations about the appearance of those in teacher and leadership roles).

There are plenty more great ideas. Check them out in the Aurora Welcome Center’s comprehensive list below!

Could you duplicate this resource at your site? As long as you have a camera and a few hours to spare, of course! (Just be sure to send out a thank you to the APS Welcome Center for the idea. Find them here: http://welcomecenter.aurorak12.org)

This version was created by staff. But other great options might include:

Inviting former Newcomers to take this on as a project (a modernized “buddy” system)

Creating a digital and/or interactive version of the handbook

Engaging teacher teams in creating grade-level welcoming handbooks

And here are a few examples of what that might look like in actuality!

(Adapted with permission from Aurora Welcome Center: Refugee, Immigrant and Community Integration. Photos copyright @DiversifiED Consulting)

TIII Series: The Home Language Survey- Ensuring Compliance and Success

The Home Language Survey (HLS), also called a Heritage Language Survey or Home Language Questionnaire (HLQ), is used in the initial process of identifying a student’s potential eligibility for English language support services. A heritage language survey usually takes the form of a brief questionnaire, which may be administered in English print, preferred language print, orally, or through a translator. The purpose of the survey is to establish an understanding of a student’s language-learning background.

Student Example: Khaled’s family has just arrived to register him for school. The family meets with an enrollment specialist at the school. When completing the survey, Khaled’s mother indicates that they are from Somalia. She also notes that Somali is the language spoken in the home. However, Khaled’s first language (and only instructional language) is Swahili, as the family relocated to the refugee camp in Kenya just before Khaled’s birth. Khaled’s exposure to the English language, at least according to the Heritage Language Survey, is limited. These results suggest that Khaled may be eligible to receive English-supportive learning services.

Home/heritage Language Surveys can be extremely useful in identifying potential new-to-English learners. However, keep in mind that these, like other student assessments, are only an indicative tool. They cannot be used as an exclusive measure for language services enrollment. (And they certainly don’t capture the cultural and linguistic funds of knowledge diverse student groups bring to the table).

Next, Khaled will be screened for multilingual programming eligibility (ELL services).

If and when an HLS confirms that a student is new to English, he or she will be considered for language learning services. The enrollment specialist (often the multilingual department head, multilingual coach, Student Assessment Liaison, or other trained personnel) carefully analyzes the data.

Specific testing may vary from state to state or from district to district. Most schools employ WIDA ACCESS, ELPA, Woodcock-Munoz or a similar state/district approved measure. Regardless of the testing instrument, timeliness is key to compliance, but more importantly, as part of our commitment to meeting the learning needs of the child.

It is critical to note that the Heritage Language Surveys (or any other form of registration questioning) is limited in its capacity. That is, no information obtained through school enrollment can be used to evaluate, comment or report on legal immigration status. Federal law strictly protects the rights of all children who are present in the U.S. to attend public school; and it conversely restricts school personnel from any inquiry or interference in legal immigration issues.

I always suggest that schools walk through a HLS “Think Tank” , whether they are starting from scratch to build a questionnaire or have an existing process in place. Here are some of those Think Tank prompts:

What is the schools’ defined purpose for the Heritage Language Survey? (In other words, how and why is the survey meaningful to students and parents?)

Where on campus will the survey be completed?

How is a sense of welcoming and belonging achieved during this process?

Is the assessment culturally responsive? how do we know?

Who at your school will administer the Heritage Language Survey? What is their level of training/expertise to do so?

Who at your school will evaluate the HLS responses? What is their level of training/expertise to do so?

In which languages are print copies of the HLS made available?

In which languages can the HLS be verbally translated/communicated?

Is the language concise and clear?

Are families informed that information is confidential and cannot be used for any outside purpose (including immigration status)?

If a student is highlighted as potentially eligible for English Support Services services, what is the next-step process?

How is Emergent Multilingual (EM) testing and placement information recorded and stored?

How often are student HLS documents revisited/ re-requested?

Finally, let’s explore an HLS example. You’ll find that the first page can be used as a ready-to-roll version, or as a baseline for creating a site-specific version. The template is exactly as we have described, with essential questions for determining potential language services eligibility. That’s it. That’s all you need.

However, you may find it useful to collect additional data. In that case, the additional pages of the survey will provide ideas with regard to collecting additional data and insights about the student and his or her family. Additional data collection is optional for the school, depending on your school’s needs and program goals. It is ideal to have as much information about a student’s specific background and needs at the time of enrollment. The HLS addendum serves this purpose.

Note that if you do choose to ask for additional data, caretakers are not obligated to provide it. If families choose to exercise their right to withhold data, this decision cannot affect child enrollment in any way. In any case, consistency is key. Make it a goal to have 100% incoming family participation in completing the questionnaire.

Crossing Cultural Thresholds- Engaging EL Caretakers in the Trauma-Aware Conversation

Let’s look to tools and strategies that facilitate re-directive capacities and champion long-term moves toward resiliency. We’ll spend a bit of extra time focused on our Recent Arriver Emergent Lingual (RAEL) students. In this space, we’ll highlight EL parents and families as critical stakeholders in students’ trauma restoration processes.

Trauma-informed pedagogy relies upon, in part, the explicit teaching and modeling of regulatory and prosocial behaviors. Eventually, these strategies can be holistically embedded into children’s everyday school (and life) experiences. In the context of RAEL populations, this also means bridging cultural norms and expectations around mental wellbeing. As learning places, this requires a concentrated shift toward integrating diverse cultural value systems into our trauma-sensitive practice.

The National Council for Behavioral Health names two dimensions of sustainability in trauma-informed programming:

1. Making changes, gains, and accomplishments stick

2. Keeping the momentum moving forward for continuous quality improvement.

So, how can we best support these two dimensions? A sustainable path toward resilience requires us, as practitioners, to monitor students’ success and adapt our instructional cues as needed. Fortunately, we already recognize this as a best practices approach across all grade levels, content areas and language domains. We are experts at checking in on our students and personalizing the learning experience based upon individual strengths and needs. The same tenets apply to the processes of transition shock, including trauma.

Shifts are required in the broader educational landscape, too. Sustainability requires honest conversations about our organization’s infrastructure, including leadership, policies, and procedures as they ignite or diffuse underlying transition shock. It demands moving away from punitive practices and toward restorative solution seeking. Sustainability relies upon the collection and analysis of data in order to determine if our trauma-informed programming is effective and equitable. It means that all team members are equipped with tools for understanding and addressing student trauma, and that educators are widely supported in recognizing and managing the secondary stress that may arise through our work with trauma-impacted youth.

Essentially, we are charged with ensuring that the strategies we introduce are good fits for individual students. A good fit means that they are not re-triggering and are both culturally responsive and language adaptive. A good fit means that learners are empowered to experiment with mitigation strategies in their toolboxes, to fail forward in a safe space, to reevaluate without self-admonishment, and to try again.

Involving Caretakers as Critical Stakeholders

If we are to truly address transition shock (including trauma) in our learning spaces, then we must also become active in engineering webs of support around our students- in this case, we’re speaking specifically about our RAELs. Here, we’ll concentrate on arguably the most critical stakeholder group of all- the parents and caretakers of our Emergent Linguals.

In communicating with culturally and linguistically dynamic caretaker groups about transition shock, it’s important to first identify our guiding principles. How do we cross cultural thresholds to build authentic partnerships?

As with our students, safety and trust are paramount. Cultivate these properties as we would in the classroom- practice welcoming, routine, predictability, and transparency.

Be cognizant of biases around mental health and trauma. Name observed behaviors and avoid labeling.

Reduce isolation by connecting families to appropriate resources, as well as to families with socio-cultural commonalities.

Strive to meet with parents in person and, if needed, arrange for a trained translator wherever possible. Avoid using children as conversational brokers.

Talk to parents about the link between students’ school performance and socio-mental health. Use direct and clear language.

Remember that mental health terms may be unfamiliar, unmeaningful, or untranslatable for Recent Arriver parents. Translate these terms ahead of time if possible, and provide visual cues where appropriate.

Honor socio-cultural perspectives when advocating for student care.

Champion wrap-around supports and refer students for advanced care in a timely manner.

Sustainability is enhanced when students’ home and cultural values show up in the school space. Highlighting the voices of our RAELs’ caretakers can simultaneously bolster our culturally responsive efforts and temper student anxiety. Meanwhile, opening doors to culturally responsive communication around trauma-sensitive topics builds trust and enables a collaborative approach to long-term restoration.

What Is Sheltered Instruction?

Effective Recent Arriver programming is structured with the principles of sheltered instruction in mind. These techniques are not tethered to an exclusive program or curriculum. Rather, they are tools for teaching and learning that can be applied to and incorporated into any existing program to explicitly promote language development. All sheltering strategies are centered around the primary goal of increasing Emergent Multiinguals’ access to (and demonstrated mastery of) essential knowledge- without compromising the integrity of the content lesson.

Strategies that are associated with this pedagogy foster academically focused student talk, intra and interdependent problem-solving skills, effective collaboration, and healthy cross-cultural communication skill development. These practices benefit Recent Arriver and traditional students alike and can be modified to support learners across a range of language, grade, and skill levels.

Where Did the Term Sheltered Instruction Come From?

Sheltered instruction is a manifestation of the Comprehension Hypothesis for language learning. The Comprehension Hypothesis is rooted in the idea that “we acquire language when we understand messages containing aspects of language that we have not acquired, but are developmentally ready to acquire.” (Krashen, 2013). That is, language learning best occurs in natural settings, drawing holistically from what we hear and read. It develops via exposure to comprehensible input, or bite-sized digestible pieces of language understanding.

This is in direct contrast to the skill-building theory, which presses for direct, rote learning of grammar, vocabulary and spelling knowledge. Briefly, skill-building strategies are conscious measures, while comprehension-based learning is subconscious and indirect. Research overwhelmingly indicates that language learning is enhanced and accelerated when Comprehension Hypothesis methods are applied. In fact, evidence shows that,

“Students in beginning-level second language classes based on the Comprehension Hypothesis consistently outperform students in classes based on skill-building tests of communication, and do at least as well as, and often slightly better than, students in skills-based classes on tests of grammar.” (Krashen, 2003)

Sheltered instruction is directly representative of Comprehension Hypothesis ideals. Its primary goal is to provide language learners with a comprehensible input through the implementation of specific instructional tools and practices. Sheltered instruction is critical in the context of Newcomer instruction in that it focuses on content over language.

When students are exposed to content knowledge in comprehensible ways, appropriate language output is a holistic byproduct. Additionally, anxiety and pressure to learn the new language may be significantly diffused in sheltered subject matter settings. In fact, “Students in sheltered subject matter classes acquire as much language or more language than students in traditional [ESL-direct] classes and also learn impressive amounts of subject matter”. (Krashen, 2013, 1991; Dupuy, 2000)

So, what does sheltered instruction look like in the classroom?

Sheltered, or scaffolded, instructional practices engage emergent bilinguals and multilinguals in the rigorous content investigation. It can encompass a wide range of instructional techniques, each aimed at guiding and directing language learners toward proficiency, within an environment that endorses safety and facilitated risk-taking.

At the crux of impactful scaffolded instruction are effective content language learning objectives, which can be incorporated into every subject, each day. These cornerstones provide a powerful sense of directionality for both the educator and the learner and fuel a focused sense of productivity.

Basic elements of sheltered instruction include:

appropriate pacing;

modified speech;

routine and predictability;

use of visuals, realia, and manipulatives;

explicitly introduced body language, gestures, and facial cues;

sentence stems;

relevant language supportive technology;

modeling;

traditional or interactive word walls;

interactive notebooking;

multiple modes of assessment/means of demonstrating understanding;

graphic organizers (such as Frayer models, Venn Diagrams or word-mapping);

co-operative talk structures, such as inside-outside circles, fishbowls, numbered heads (download your cheat sheet here);

SIOP lesson planning, or “Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol” (Echevarria & Short), is frequently implemented as part of sheltered-instruction instruction.

When we integrate sheltering techniques into existing curricula and classroom protocol, we invite emergent bilingual and multilingual students to engage with intention and purpose, in ways that highlight existing funds of knowledge. We also support team building and interpersonal skills, which lend themselves to healthy integration. Perhaps most importantly, sheltering strategies can be overlapped with other pedagogies, such as culturally responsive teaching and learning, leading to especially dynamic socio-academic student outcomes.

For detailed information on Sheltered Instruction techniques, see The Newcomer Student: An Educator’s Guide to Aid Transition, Chapters 6-8

Download your Co-Operative Learning Cheat Sheet HERE.

Newcomer / Recent Arriver Classroom Reminders

We’re into the thick of the year. It’s a great place to pause and reflect on our practice so far this school year and how we will grow our students in the remainder of our time together. It’s a great time for Newcomer/Recent Arriver classroom reminders! Here, we’ll look at the non-negotiables.

What would you add? Be sure to share your thoughts below.

FOUNDATION

Classroom culture drives learning. Newcomer students thrive in classrooms that are safe, structured and predictable. In fact, predictability is a cornerstone of positive school engagement. Predictability breeds trust, trust lends itself to safety, and safety opens students up to entertain curiosity, absorb content and practice positive risk-taking in the classroom.

DIRECTION

It is important to lead with a plan and to ensure that the plan supports equitable participation for all students, including students who are new to the English language. Content–Language Objectives (CLOs) are an effective tool for creating a specific language focus (with the purpose of enhancing content accessibility for ELLs). They are widely flexible and can be implemented across all grades/subjects and for any number of ELs in a class. Content–Language Objectives guide lesson planning and ground student understanding throughout the lesson.

PLANNING

In preparing for English Language instruction, there is a tendency to over plan. When it comes to lesson planning, aim for relevance and quality, not quantity. Return to the Content-Language Objectives. Ask: 1. What one strategy will be most useful to my learners in making the key content more digestible? 2. What one strategy will my students use to demonstrate the language objective within the target language domain (reading, writing, speaking, listening)?

Can more than one strategy be implemented? Of course! Just be sure to aim for clarity. If things start feeling jumbled or unclear, return to your one original focus for each question. Our students will always perform better when they know exactly what is expected of them.

COMMUNICATION

It’s important to keep in mind the amount of fo language that students encounter in a given school day. Beyond the conversational language that must be learned to navigate the bus, playground or lunchroom, learners encounter languages within the language throughout the entire school day.

Let me explain. If conversational English (with its slang, reduced speech and media influences) is a tongue, so is the Language of Mathematics. Isosceles, divisor, and equation are not words students are likely to pick up in their informal conversations. This type of (academic) vocabulary must be explicitly taught. And if Math is a tongue, then so is the Language of Social Studies, the Language of Music, the Language of English Literature, and so on.

Our students encounter thousands of words in a day. For ELLs, this can be especially overwhelming. To reduce the language load, we can be intentional about listening to ourselves. How might we describe the rate and complexity of our speech? How can it be modified for clarity?

In short, here’s what we’re aiming for: Speech should be clear, deliberate and unrushed. (Side note: Louder or painfully elongated speech is not helpful.)

EXPRESSION

Language encompasses so much more than just vocabulary. Tone, register, slang, cultural cues, humor, sarcasm, reduced speech, body language, facial expressions, and gestures must all be negotiated in the context of learning a new spoken language. Gestures, or the motions and movements Gestures can be used to enforce an idea but should become less exaggerated with time, as understanding grows. Where possible, normalized conversational gestures are optimal.

PACING

ELLs often require a longer “wait-time” to produce a response. After questioning, allow up to two minutes of unprompted thinking time. If a student is not yet ready, offer cooperative opportunities for production. Partner-Pair-Share, Numbered Heads, or Rally Table are great approaches; and sentence starters can be embedded into any of these strategies. Just be sure that the student who was originally asked does, ultimately, have the opportunity to share his or her response with the class.

APPROACH

Labeling, visuals, realia, manipulatives, graphic organizers, sentence frames and hands-on exploration are essential to the ELL classroom experience. Each is a language-building path toward content accessibility. Additionally, we can be especially mindful that our curriculum and class reading materials reflect the diverse nature of our classrooms. Where do our students recognize themselves in the school day? How are students invited to express themselves using the four language domains?

PROCESS

Students, including English learners, should have guided agency over their own learning. Work with students to set goals, create viable paths toward these aims, and to monitor their success along the way. Cooperative structures are an important part of this process, as they encourage language development, enhance positive classroom culture and put students in the drivers’ seats of their own learning. Yes, our ELLs CAN meaningfully participate in student-led instruction and Project-Based Learning (PBL). Learn to establish supports… and then get out of the way!

CONSIDERATIONS

Newcomer students may be working through trauma, shock or other stressors. Monitor external stimuli to help mitigate significant stress. Learn to recognize symptoms and know when to ask for help. Work to recognize, celebrate and practice Socio-Emotional Learning (SEL) skills throughout the school day and school year. To build background on newcomer Trauma start HERE. For more tips on trauma-informed care for ELLs (and all students) take a peek at an RC article for Edutopia, found HERE.

INVITATION

You may be a child’s first teacher of their school career, their first teacher in America, or the first teacher to breakthrough. Smile. Show welcoming. Be an example of the possibility that exists for them.

Digital Game Play for Instruction: The Why of the Practice

I recently wrote an article for Edutopia outlining 5 Free Video Games That Support English Language Learners. In this article, we’ll lay some groundwork in terms of understanding the whys and hows of using serious games to drive meaningful student learning. Our guiding question: What makes gamification so appealing, and how can we apply this to our classrooms to increase student engagement and accelerate content understanding?

The Edutopia article explains: “The concept of gamifying learning has been part of practical instruction, in various forms, for years, and for good reason: Research shows that game-based learning has the capacity to motivate students, activate knowledge and enhance critical thinking capacities.” Additionally, we know that gameplay is a key facet of culturally responsive teaching and is an integral feature of modern ESL curricula. Serious games and simulation games, which invite players to actively solve for real and relevant problems, also expand the ways that learners see and interact with the world.

Trends in games-based learning continue to lean into technological integration- and data backs up its place in the 21st-century classroom. In fact, research indicates that education-focused video and virtual gaming can benefit all students, particularly low-performing students who demonstrate the greatest need.

Video games- including educationally driven programs- follow a predictable structure, resulting in relatively uniform user experience. If we look closely, we see that video game design takes many of its leads from brick-and-mortar classrooms. In fact, a user’s interaction with a gaming interface mirrors the school learning experience, where instructional best practices are in place.

Video games are largely successful at capturing users’ attention and driving players toward mastering the content of the game. In a similar way, it is possible to recognize key features of gaming architecture in our classrooms and to leverage these features to increase student interest and motivation and to drive authentic content learning.

Let’s take a closer look at those components:

· Play: Play is the cornerstone of video game design and appeal. Play itself has several requisites: choice, positive peer interchange, and the opportunity to explore, coach and learn in a safe, non-threatening arena. Schools also recognize the power of play, including the elements of healthy social interaction and cultivated trust, and we cater to it in a variety of ways.

· Central goal: A game is separated from simple play by one defining feature: the presence of a central goal. Well-designed video games direct users toward a clear and attractive end goal. Well-organized classrooms lead students toward specific, achievable end goals, usually through a series of identified mini-goals. We name these standards, student learning outcomes, or Content-Language Objectives (CLOs).

· Rules: Rules are the skeleton of a game. In a video game, rules-design follows the principle that rule followers will advance to the next stage of the game; and for those who misunderstand or abuse the game’s rules, the process will be delayed or ended. This pattern applies to most areas of life and is evidenced in the classroom setting. When expectations are clear, students understand what is expected of them and can respond appropriately.

· Feedback: The feedback loop is central to digital gameplay. The user voluntarily completes an action, which stimulates a system response (feedback). The user interprets the feedback and reacts accordingly. This process continues until the game ends or the user terminates the loop.

As educational practitioners, we are experts in feedback loops. The difference is that technological feedback is direct, instantaneous and wholly interactive. We know that prompt and meaningful feedback has positive implications for intrinsic motivation and accelerated learning. How can we grow in this capacity to benefit our students?

· Voluntary Participation: Virtual gaming is rooted in choice. When personal choice is introduced, productivity, accuracy and motivation increase. Where can we make room for more student choice in our classrooms? Interactive station rotations, student-led inquiry and project-based learning, for example, all promote voice and choice.

· Personalization: Video games are designed to read the user. They must determine the player’s initial level of expertise and projected wants and needs- and then adapt to fit the player. Well-designed games scaffold learning and progressively increase in complexity. This mimics optimal instructional protocol for all learners, including linguistically diverse students.

· Removed Fear of Failure: In game play, users are afforded an infinite number of opportunities to try again. Mistakes become synonymous with new prospects- and ultimately, failure becomes obsolete. The idea of “failing forward” is inherent to the gaming world. Where and how can we work toward removing fear of failure in our schools?

· Community Building: Virtual games lend themselves to collaboration and community. This is enhanced within the backdrop of joy, entertainment, belonging, teamwork… and fun. Positive relationship building is also central to the school organism. It forms the backbone of SEL, culturally responsive teaching, and trauma-informed practice.

· Assessment: Video games are also assessments: they recognize, evaluate and rank participation- and then adjust the experience accordingly. In this context, assessments are also malleable. They adapt to the player’s understanding and expertise and automatically push forward (or fall back to re-teach). Our best site-based assessments look this way, too!

· Debriefing: Debriefing is the process of thoughtful, purposeful reflection on one’s experience. Educational gameplay should include debriefing as a way to complete the circuit of understanding. In the classroom, this process can be guided and modeled and my included speech, writing or other expressive means.

Gaming is not intended as a replacement for quality instruction delivered by an experienced teacher. However, educationally purposeful video games can support students’ learning in a host of ways. And if we take the time to see it, we’ll find that tech-based gaming has more in common with traditional educational structures than we might realize- that the overlap, in fact, is significant.

Understanding Student Identity: Diving into Race, Ethnicity and Culture

What constitutes identity? From one community to another, and from one school campus to another, we are likely to find widely varying explanations.

Conversations around identity are typically assigned bank of related vocabulary. Often, we employ these words – race, heritage, ethnicity, nationality, and culture- interchangeably.

This is problematic, and often muddles our concept of (and ability to recognize, embrace, and value) personal identity. It makes it easier to lump human distinctions into tidy categories based on a series of checkboxes. But the reality is, it’s just not that simple.

Race is vastly different than ethnicity, and heritage does not necessarily indicate culture. Fortunately, getting these concepts straight is not highly complicated, either. It just requires that we have a common working language. Let’s get to it.

First, let’s return to our vocabulary: Race, Ethnicity, Nationality, Heritage and Culture.

To organize these concepts in our heads, we can think of the elements as concentric circles. When I’m working with folks in a professional development setting, those pieces fit together like this:

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Let’s first look at the concept of “race” within the larger outside circle. Here’s the definition we’ll use for race: the composite perception and classification of an individual based upon physical appearance and assumed geographic ancestry; a mechanism used to facilitate social hierarchies.

Race, then, is an invented construct designed to enhance the social maneuverability of some and diminish that of others. If we look to our human history, we can see that the concept of race has been effective in achieving this aim. But the concept is overtly simplistic. Essentially, majority parties create arbitrary social categories that label those apart from them, and them fill in those categories with identifying descriptors for each category.

Race is also a malleable property. Racial categories (and their descriptors) differ from one society to another and change over time. They are susceptible to shifts in power, demographics, and socio-political climate. In the U.S., we’ve historically defined those race categories by color: black, brown, white, yellow and red.

Of course, we know that there must be so much more to the story than this.

The idea of ethnicity gets us a bit closer. We’ll describe ethnicity this way: An individual’s tie to a to a broader social group as defined by shared language and value systems, which may include nationality, heritage, and culture.

Ethnicity is a richer value than race. It captures the many elements that link a community of together. It also encompasses both past and present values of a social group. The most defining feature of ethnicity is that is self-definition. While one may be “born into” certain features of ethnicity, an individual may choose to abandon, adjust, or add to his or her ethnic identification.

The choice aspect of ethnicity also leaves room for ‘and’. Cherokee and Lakota. Latina and Korean. Palestinian and French. Igbo and Yoruba. Black American and white American. Multiethnic. Polyethnic.

This singular aspect of choice is what sets race and ethnicity apart. While both are inventive concepts, race exists only as an external social construct, placed upon an individual without choice. Ethnicity, meanwhile, exists as an internal construct with external influences and is marked by the mechanism of personal choice and affiliation.

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Nationality, heritage and culture may be viewed as separate from, but somewhat living under the umbrella of ethnicity. Language is also housed here. Language represents the means of interpersonal exchange between peoples of a country or community. It is also the conduit through which elements of ethnicity (including nationality, heritage and culture) are expressed.

Nationality refers to the country to which an individual was born, holds citizenship or identifies with as home. The element of choice is observable here. A student who was born in Russia but has lived in the United States since the age of six is likely to have a very Americanized world-view and may identify as American, even if her citizenship status does not reflect this.

The idea of heritage looks to the place or places from which one’s ancestors originated from and what those ancestors subscribed to. It is possible to identity with a heritage, but not the matching ethnicity. For example, a person may recognize his African descent, but identify as ethnically Afro-Caribbean. An individual may celebrate Irish heritage, but not speak the language or identify with customs linking it to that ethnicity.

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Finally, we arrive at culture. Culture, in many ways, is the most complex value. It is similar to ethnicity, but in a way, nested within it, as cultural indicators are part of the architecture of one’s ethnic identity.

Culture relates to the specific combinations of socially acquired ideas, arts, symbols and habits that make up an individual’s day-to-day existence and that influence his or her social exchange. So, ethnicity has to do with overarching themes that define a particular social group. Culture presents itself as (often material) markers of the ethnic group or its subgroups.

Culture has other attributes that set it apart from race, ethnicity, nationality and heritage. Namely, it is not determined by appearance. Culture is also a fluid property and is largely influenced by personal choice. Cultural behaviors may be changed, shared or acquired. Any person may pick up another’s culture at any time, and a person’s culture is highly likely to change over time, in whole or in part, based on new experiences, interests, and social influences.

For staff Professional Development information on this topic please visit HERE. @ElYaafouriELD for DiversifiED Consulting 2018.

Often, the element of culture is further broken down into three layers: surface, conscious and collective unconscious. Zaretta Hammond, in her incredible work, refers to these areas as surface, shallow and deep culture. Surface culture mostly refers to observable markers: fashion, food, slang, art, holidays, literature, games and music. Conscious culture looks to the governing rules and norms of a community. It includes eye contact, concept of time, personal space, honesty, accepted emotions, and gender norms.

The collective unconscious culture is at the very core of one’s worldview. From this space, an individual processes the natural and social world- and also makes sense of his or her place within it. Spirituality, kinship, norms of completion, and the importance of group identity are all part of the collective unconscious.

It is also possible to have sub-cultures with our culture. For example, we may belong to a skateboard, cowboy, gaming or band culture. We can attach specific elements of action and expression to each unique social behavior/interest group.

Now we can step back and look at our map. When we put all of these elements together, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of what comprises an individual’s identity. We can move in the direction of looking past the first layer of race (and perhaps eventually remove this non-serving piece). We can, through culturally-responsive teaching practices, develop our expertise in peeling away layers in our students’ identities in order to explore the deep culture factors that truly drive belonging, motivation and learning.

Refugee 101, Part 2: Who is a Refugee?

Image is part of a learning video created by Louise El Yaafouri for Colorado Refugee Connect. View the full video and get involved at corefugeeconnect.org.

Currently, there are more than 65 million displaced persons in the world. Of those, nearly 26 million are classified as refugees. More than half of the world’s refugees are children.

Less than half of one percent of the world’s refugees will ever be resettled to a third party country, such as the U.S. A slight handful of that exceptional one percent will make their way into our schools and classrooms. This means that our newcomer students truly are one in a million- and in the broader context of displaced persons, closer to one in a billion.

As educators, we may be presented with the unique opportunity- and awesome responsibility- to serve students from refugee backgrounds. In this five-part series, we’ll explore the refugee experience, outline pre and post-resettlement processes, and celebrate resettled refugees as assets to our communities.

WHO IS A REFFUGEE?

Migration is a central theme of the human story. Many, including including immigrants and migrants (by technical definition), relocate by choice- usually in search of new opportunities or improved ways of life.

Others are forced to relocate as a means of survival. Displaced individuals are pushed from their homes or communities involuntarily and under high duress- often leaving behind possessions, loved ones and personal histories. Catalysts for displacement include war, famine, natural disaster or economic instability.

Refugees are set apart from other displaced populations by one critical feature. The flight of a refugee must be related to war or violence, and they must experience an earnest fear for their life as a result of ongoing persecution.

This comes from the 1951 Geneva Convention, the outcome of which defines a refugee as one who fled his or her own country because of persecution, or a well-founded fear of persecution, based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. Asylum seekers meet the criteria of a refugee but are already living in the host country or are seeking asylum at a port of entry.

Image is part of a learning video created by Louise El Yaafouri for Colorado Refugee Connect. View the full video and get involved at corefugeeconnect.org.

Each story of the refugee experience is unique. Some travel through multiple countries in search of asylum. In the process of escape, many must tolerate uncertainty or entrust their lives to smugglers. Some endure periods without food, water or shelter. Many flee without important documentation. Some are forced to leave loved ones behind.

The majority of refugees relocate to urban camps, where groups of affected individuals band together within established cities. Urban camps are generally makeshift and may evolve to have their own economies. Some resettle in formal refugees camps, typically organized and operated by the UNHCR. These are the image of refuge camps that most Westerners are familiar with, usually having standardized tent structures and organizational staff.

From The Newcomer Student:

It is difficult to capture the essence and extent of what a refugee camp actually is. Refugee settlements are not typically self-supporting, and rely extensively on external aid for nearly all matters of finance, food, health, and viability. They are notoriously unglamorous, routinely undersupplied, and statistically dangerous. The UN High Commission for Refugees offers that, “Refugee camp is a term used to describe human settlements which vary greatly in size and character. In general, refugee camps are enclosed areas, restricted to refugees and those assisting them, where protection and assistance is provided until it is safe for the refugees to return to their home or to be resettled elsewhere.”

On average, a refugee lives in a camp setting for 17 years. It is common for refugees from one country to be born in a refugee camp in another country (for example, a Bhutanese student may identify as Nepali, a Burmese as Thai, or a Congolese as Tanzanian.) On average, a refugee is away from the heritage country for 20 years before a return can be realized.

Prior to upheaval, most refugees did not desire to leave their home countries. In fact, this process can be very traumatic. In her poem “Home” Somali poet Warsan Shire writes, “No one leaves their home unless their home is the mouth of a shark.”

SOURCES:

American Immigration Council (2013). Located at americanimmgrationcouncil.org. Retrieved Oct. 2012.

Russell, Sharon Stanton (2002). Refugees: Risks and Challenges Worldwide. Migration Policy Institute, 1946–4037.

Hamilton, Richards & Moore, Dennis (2004). Education of Refugee Children: Documenting and Implementing Change. In Educational Interventions for Refugee Children, eds Richard Hamilton & Dennis Moore, London UK: RoutledgeFalmer, Chapter 8.

McBrien,J.Lynn(2003).A Second Chance for Refugee Students. Educational Leadership, Vol. 61, No. 2, 76–9 O. Educational Needs and Barriers for Refugee Students in the United States: A Review of Literature. Review of Educational Research Vol. 75, No. 3, 329–64.

United Nations, High Commissioner for Refugees (2012). United Nations Communications and Public Information Service, Geneva, Switzerland. Located at unhcr.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

Patrick, Erin (2004). The U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program. Migration Policy Institute, Washington, D.C. Located at migrationpolicy.org/article/us-refugee- resettlement-program. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

United Nations Convention related to the Status of Refugees (1951). UN Article 1. Located at unhcr.org. Retrieved June 2011.

International Refugee Committee (2015). SOAR, New York. Located at rescue. org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

Van Hahn, Nguyen (2002). Annual Report to Congress- Executive Summary. Office of Refugee Resettlement. Located at acf.hhs.gov. Retrieved Dec. 2010.

Edwards, James R. Jr. (2012). Religious Agencies and Refugee Resettlement. Center for Immigration Studies. Memorandum, March 2012.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2012). United Nations Communications and Public Information Service, Geneva, Switzerland. Located at unhcr.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

U.S. Committee for Refugees & Immigrants (USCRI) (2015). Arlington, Va., refugees.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

U.S. Committee for Refugees & Immigrants (USCRI) (2015). Arlington, Va., refugees.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) (2013). Path to Citizenship. Located at uscis.gov. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

U.S. Committee for Refugees & Immigrants (USCRI) (2015). Arlington, Va. Located at refugees.org. Retrieved Aug. 2015.

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) (2013). Path to Citizenship. Located at uscis.gov. Retrieved Aug. 2014.

Refugee 101, Part 1: An Introduction

The only remaining photo of Eh Doh Htoo and his family in the Thai refugee camp for Karen Burmese. He shared this photo with our class as part of a “Heritage Book” project in 2009. He graduated high school last year.

The following is an excerpt from The Newcomer Student: An Educator’s Guide to Aid Transition by Louise El Yaafouri (Kreuzer), available HERE.

An Introduction to the Refugee 101 Series

Newcomer students are often defined by a long and complicated series of statistics: data scores, influx patterns, poverty analyses, and of course, school performance grades. Certain figures are certainly useful and valid. But they lead us apart from the relatable, tangible person. The relatable, tangible student; the learner we show up for. This leads us to the who.

In elementary talk, human seeking refuge is the main idea of the refugee story. Refugees are individuals with palpable faces and names who are colored by real life stories, experiences, families, and successes. Refugees and immigrants, not apart from our host-nation selves, are people—parents, children, adventurers, workers, dreamers, teachers, students, feelers, believers, doers, and learners.

Again, like us, refugee individuals and families carry with them other things: tribulations, stressors, and personal legacies. Some family fabrics are cohesive; others show wear. Some individuals appear well adjusted and decodable, while others are stalemated in secrets, burdens, and internalized fears.

These pieces, combined, highlight one simple, beautiful, extraordinary truth. We are all human. Each of us is susceptible, and yet, each of us is a channel for resiliency. We are all magnificent and full of promise, just as we are tarnished and unsteady. Each of us owns an access point to greatness. More than this, we all possess the inherent ability to help and guide one another through processes of personal and contextual transformation.

Let’s think this through. Are we, as westernized Americans in our own subjective neighborhoods, so exempt from characteristics of trial, loss, joy, confusion, relocation, or overcoming? Of course not! Sure, some of our stories register relatively low on the scale of global severity. Nevertheless, our personal tribulations and successes are meaningful to us, within the context and perimeters of life as we are familiar with it. No story is insignificant.

Greatness belongs to each of us.

"Home": Acknowledging the Complex Transitions of Refugee Newcomers

Drawing by former student Pah Leh Paw (age 9), depicting the Thai refugee camp where she grew up, after her family fled from the Karen cultural region of Myanmar Burma.

“I AM FROM . . .”

In my first year of teaching in the Newcomer sector, I remember feeling flabbergasted by one very real truth: our little four-walled classroom housed the world inside its perimeter. Out of the twenty-five students that first year, fourteen countries were represented in our classroom, with nineteen first languages among them. I still cherish this memory, and perhaps more so now that I’ve also acquired some understanding of the unique countries, customs, and languages that we have in our care.

I arrived as head of the classroom that year, the first year that our refugee-magnate school was set in motion, highly unprepared. I was fresh, sure, and knowledgeable in the field of education, too. I was also remarkably naïve. Armed with personal monologues of out-of-country experiences, I thought I was worldly, exposed, and ready. Then, I got schooled by a class of eight-year-olds.

When, for example, students stated, “I am from Burma,” I assumed, well, Burma. As in, one Burma, the one I located on Google Maps (just to refresh my memory . . . of course). As in, one culture, one language, one struggle, one united journey to our classroom.

That episode of simplistic thinking was short-lived. Within days, I figured out that several of my Burmese students couldn’t actually communicate orally with each other. Moreover, this group of students did not always appear outwardly friendly toward one another, despite their apparent cultural similarities. In fact, I was noticing intense tensions and aggressions between like-cultured groups, even while cross-cultural communications remained friendly and outgoing.

At one point early in the year, Snay Doh came to see me in private. He asked to move his seat away from his Thai peer, Thaw Eh Htoo. He wished to sit at a separate desk, between Valentin from Burundi, and Khaled from Yemen. “I don’t mind thinking about this, Snay Doh,” I replied, “but I hope that you can explain to me why this is a good idea. Moving your seat isn’t going to make a bigger problem go away. What is it that seems to be keeping you and Thaw from getting along?”

Snay Doh, with his limited English vocabulary, broke down the entire dilemma, with Crayola illustrations and all. In the end, I learned that Snay Doh’s parents were Burma-Burmese, and that he was born in the refugee camps in Thailand. Thaw Eh Htoo was also born in a Thai refugee camp. However, his parents were Karen Burmese. Not only were these two families from geographically, linguistically, and culturally separate parts of Burma; they were also at war with one another.

With a little more research, I came to realize that four rivers physically separate the small nation of Burma into five distinct geographical regions. Within these regions, a multitude of individual tribes maintain separate and exclusive lifestyles and cultures. Seven of these tribes demand high social and political prominence. These clans have an epic history of interaction, often involving warfare on every level and for every reason: territory, religion, water, trade, and government.

Members from five of these tribes held places on that first year roster. So, no; that original seating arrangement with four of those Burmese students, of four separate religions, customs and dialects at the same table didn’t work out so well. (Enter school-wide positive behavior system roll-out.)

Similar dichotomies are repeated each year in our schools and classrooms, and are reflected in the lives of our students from all over the world: Congo, Iran, Somalia, and Libya, and many others. The truth is that people who originate from one country are not necessarily homogeneous, or for that matter, oozing with camaraderie with one another. Fundamental views and values may vary dramatically, even to the point of enmity. For me, this lesson was critical. Indeed, we are never done learning.

AS THE CROW FLIES

Interestingly, our students’ documented countries of origination are rarely aligned with actual ancestral roots. This occurs primarily because many of our students are transported to (or even born in refugee camps) proximal to the heritage region.

For example, most Nepali refugees are Bhutanese. Many Thai students are Burmese. Our Kenyan students might be exclusively Congolese, Somalian, Rwandan, or Ethiopian. A Lebanese student’s first home may have been Syria, Palestine or Afghanistan.

Sometimes a spade is a spade; Congo really does mean Congo, and there is no need to complicate things further. But often, it doesn’t hurt to engage in a little sleuthing. The results can be astonishing. Frequently, Newcomers will have lived in a multitude of nations, even leading up to the country of origin that appears on resettlement documentation. This information can be helpful, in that it allows for additional insights into students’ probable cultural and learning backgrounds. It might also sway us away from topical assumptions and approaches to our craft. Cultural geography 101, via the wide-eyed testimonies of our learners.

The list below indicates possible refugee origination locales. The perimeter countries represent heavily documented home nations. The adjacent regions are plausible induction zones. Often, grouped nations may be interchanged as first, second, or third origination countries. Of course, this resource equates to a rough-sketch approximation guide. The only true authorities on our students’ pre-resettlement paths are our students and families themselves.

POTENTIAL REFUGEE ORIGINATION LOCALES

Nepal: Bhutan, Tibet

India: Iran, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, and China

Kenya: Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Somalia, Sudan, and Ethiopia

Ghana: Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Liberia, Togo, Benin, Mali, Nigeria, and Senegal

Egypt: Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Libya, Syria, Djibouti, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Yemen, Congo, and Lebanon

Libya: Tunisia, Lebanon, Syria, Eritrea, Sudan, Senegal, Egypt, Somalia, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo, Yemen, Djibouti, and Algeria

Thailand, Malaysia: Myanmar Burma, Karen Burma, Chin Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and China

Bangladesh: Rohingya Burma, Urdu Pakistan, Iran, Philippines, and Vietnam Jordan: Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Armenia, Bosnia, Serbia, and Afghanistan

Turkey: Russia, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan

Brazil: Venezuela, Honduras, Paraguay, Ecuador, Columbia, and Costa Rica

Mexico: Costa Rica, Guatemala, Haiti, Jamaica, Columbia, Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Honduras, and Chili.

8 Ways to Optimize a Learning Culture... and Celebrate Diversity

Culture. It’s the latest education buzzword to catch fire, and it is applied to a seemingly endless range of affairs. We refer to our students’ heritage cultures. We toss around the idea of a school culture, a classroom culture, a staff culture. So, what exactly are we talking about here? In the simplest possible terms, we can look at it in this way:

“Culture is the way you think, act and interact.” –Anonymous

From this lens, it is indeed possible to reference "culture" across such a variety of social platforms. How our students think, act and interact at home and in their communities is a reflection of their heritage culture. How we think, act and interact at work is a reflection of our work culture.

Let’s consider our schools and classrooms from this same vantage. Looking to the best versions of ourselves and our programs, what do we envision as an optimal learning culture for our students and staff? How are we encouraged to think, act and interact with our students and colleagues? How are we teaching learners to engage with each other in affirmative ways?

As a school or classroom leader, these are important thoughts to map out. My ideas may not look the same as your ideas. That’s ok. We can lay some common ground, though. The following cues present an opportunity to check in with your own vision of school culture. How can you help to improve the way that your team thinks, acts and interacts?

1. Invest in Students

We all ache to know that someone we care about is standing firmly behind or beside us. If our aim is to increase a student's success rate, our honest investment in both their present capacity and future potential is non-negotiable.

Express a genuine interest in each individual. Learn how to pronounce student’s names correctly and begin using them on the very first day. Ask questions about students’ heritage culture and allow for safe opportunities to share these insights with other classmates. Offer relevant multicultural reading materials. Post flags or maps, and have students mark their heritage country. Be a listener. Find out what students find interesting. Commit to supporting students with time-in over time-out. Show up. Keep promises. Practice being present and mindful with students. Nurture connectivity.

2. Provide Choice

When presented with choice-making opportunities in a safe, predictable environment, learners develop self-efficacy and strategizing abilities. We can scaffold these processes to enable students to grow as wise decision makers. Begin by limiting the range of available options. Model reasoning through active think-alouds.

Also, it is important to allow time for students to consider and process potential gains and sacrifices involved when choosing between items or activities. Similarly, prompt students to predict the probable consequences of unwise choice making and to reflect on these outcomes when they occur. Incorporate choice making throughout the day. Station (center) activities, choice of paper color, homework, reading book, order of task completion and game selection are manageable places to start.

When students are invited to make healthy choices- and have opportunities to practice doing so- they are much more inclined to become invested, engaged learners.

3. Provide Clarity

Students, not unlike adults, desire to know what is expected of them. Who doesn't enjoy a road map to success? By sharing bite-sized road maps with your students throughout a school day or school year, you are helping them to succeed. “Bite-size” can be defined as 3-5 clear steps, with a target of three.

As we’ve already mentioned, clarified expectations foster routine, predictability and ultimately, a sense of safety. Be sure that instructional objectives are posted and communicated. Is your class schedule visible and correct? Do you refer to it throughout the day? Are station areas and supplies labeled (using rebus indicators, where necessary)? How often do you review key routines? Check your day for clarity. Define and refine.

4. Trust

Trust that students are wholly capable of making great choices and doing the right thing. Does that mean perfection? No. It does mean that in a healthy, facilitative environment most students, most of the time, will strive to meet the expectations set by (and modeled by) the teacher. We are intentional about setting the bar high, because that’s where students will reach. Maintain confidence that they will stretch to achieve it.

As students see that you trust them, they will begin living up to the expectation that they are probably doing the right thing. They will almost always respond by trusting you in return. Aim for autonomy. Give away power (when appropriate). Expect greatness.

5. Practice Problem Solving

Investigation that relies upon solution seeking engages students in developing deeper concept understanding and creative thinking abilities, while also building essential life skills. Problem-solving behaviors are learned. They are either explicitly taught or modeled by others. The school is an ideal incubator for nurturing these attributes.

Offer specific steps toward solving a problem. Model these thoughts and behavior patterns. Provide multiple opportunities for students to practice problem solving in a variety of subjects and contexts. View problems as “puzzles”. Solution seeking is a willed behavior. Our role is to guide the discovery of enjoyment and creative thinking in these processes.

6. Teach Critical Social Skills

Young people often need to be taught how to interact in positive ways. This is especially true in a Recent Arriver context, where layers of cultural expectation overlap often one another. Essential social skills encompass sensitivity, empathy, humor, reliability, honesty, respect, and concern.

Learners often benefit from explicit step-by-step social routines that work through these skill sets. Modeling, play-acting, and “Looks Like/Sounds Like/Feels Like” charts are also useful. Plan lessons to incorporate openings to explore and practice social skills. Offer guidance, and get out of the way. Provide cuing only when relevant. Share constructive feedback and reinforcement of positive behaviors.

Be the way you wish your students to behave.

7. Embrace “Failure” as a Success

Trying requires immense courage.

Perceived failure is a byproduct of trying. If we look at a FAIL- a First Attempt In Learning, then we are able to see that we have many more possible tries ahead of us. When we work to remove the fear of failing, we are also working to embed a confidence in trying.

Try celebrating failures outright. “Did you succeed the way you hoped you were going to?” No. “Did you learn something?” Yes. “Bravo! You are a successful learner.” Next time you fail at something, try acknowledging it in front of your students. Observe aloud what might have occurred and what part of your strategy you might change to bring about a different result. Failure is simply feedback. If we can take some wisdom from it, and adjust our sails, failure is a sure step in the right direction of success. Aim to create safety nets for trying.

8. Acknowledge Progress

A simple acknowledgement of our gains can go a long way. When we feel appreciated in our efforts, we also feel empowered to continue on a positive trajectory. Administrators, teachers, bus drivers, custodians, cafeteria personnel and after school care teams perform better in supportive environments where they feel that they are a contributive factor to the overarching success of a network. Our students, not surprisingly, also thrive in these settings.

Progress has an infinite number of faces. Growth and change can occur in every facet of learning- in academic, linguistic, social, emotional and cultural capacities.

Take the time to offer a thank you for a student’s concentrated efforts. Post students’ work, along with encouraging and reflective feedback. Share students’ growth. Acknowledge healthy choice making, positive social behaviors and persistence in the light of adversity. Help all learners to discover, refine and purposely engage their strongest attributes, and seek equity in endorsing successes publicly. Each day, relish in small miracles.

Creating Newcomer ELD Program Mission/Vision Statements

A school district’s mission and vision statements define and guide the work of the educational staff and the growth of the students. These statements are publicly visible, and serve as a pint of communication between central administration, teachers, students, families and community stakeholders. In most cases, districts and schools can also benefit from designing and implementing separate mission/vision statements that are unique to ELL and/or Newcomer programming, but that function alongside and in alignment with overarching district goals.

EL/Newcomer initiatives that operate with clear, program-focused mission/vision statements are able to set goals, monitor progress and make critical decisions to promote socio-linguistic growth of its diverse populations. Great! So, where do we begin?

The answer is, we begin where you begin. You- your school or organization- will begin this journey at a unique map point. You may model yourselves after other successful programs; and later programs may follow your lead. But, your school cannot walk step-in-step with another Newcomer-ELD education initiative.

Why? Your school is not the same as any other school. Your specific student demographics are unmatched.

Your team of educators- their personalities, strengths, opportunities for growth- are exclusive to your campus. Your team’s vision and goals and daily protocol are your own. Your children- the ones who stop to hug you on the way to the office, the ones you call to by first name for moving too quickly down the hallway, the ones you visit with in their homes on the weekends- these are your kids.

Who knows your students and their needs best? You do. Who knows the capacities and limitations of your space, resources and funding? You guessed it.

Your task is to craft- that is, to design and refine- successful Newcomer-ELD mission and vision statements that work for your organization, based on your particular set of ambitions, goals, needs and available resources.

DEFINING MISSION AND VISION STATEMENTS

Mission and vision statements are cornerstones in determining your group’s purpose and function. These declarations help to ground and guide your team as a unified organism with a clearly defined cause. Mission and vision statements are more than formalities. In the case of Newcomer-ELD programming, they serve as a map that guides us, instructionally, in the direction of culturally-responsive EL student growth.

Once they are established, they also serve as a baseline rubric for evaluating all decisions and outcomes. Your team can ask, “Does this item align with our mission and vision? If not, how can we effectively adjust or release it?”

Your mission statement defines what your group aims to accomplish in the present context- right now. The goals outlined in the mission declaration should be realistic and attainable. The vision statement outlines your team’s long-term objectives or ideals- your vision for the future.

Let’s look at some broad examples. Here’s Google’s mission statement: “Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. Their vision statement is “to organize all of the data in the world and make it accessible for everyone in a useful way”. (Google online, 2016)

Google works to organize and make information accessible right now. Organizing data for the entire world is a lofty objective that will take time, but could actually be accomplished at some point in the future.

Mission and vision declarations do not need to be complicated. In fact, simplicity is best. Ikea’s current mission is to “make everyday life better for their customers”. Current is emphasized because mission statements can be utterly static and should be revisited frequently as the team’s success or understanding progresses.

Meanwhile, Ikea’s vision is, “to create a better everyday life for many people. We make this possible by offering a wide range of well-designed, functional home-furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.” The phrasing as many people as possible indicates a long-range goal, or vision, for the future.

I bet you’re thinking, “That’s great, but why are we talking about Fortune 500 companies? We’re trying to get our Newcomer Centers and ELL programming off the ground!” Well, we can approach that very aim with a business-like mind for strategy, organization and anticipated gain (in this case, language acquisition, social integration and academic accomplishment). In this context, mission and vision statements are certainly applicable. Let’s examine some approaches in the educational realm.

Pearson Education details their vision and mission as:

“Our Vision: To fulfill the educational needs across a spectrum of individuals with reliable experience and technology. Our Mission:

· To provide end-to-end education solutions in the K-12 segment.

· To become a leader in the education services field.

· To create comprehensive educational content that can be delivered through a series of innovative mechanisms, thus removing physical and cultural barriers in knowledge dissemination.

· To be a vehicle of change by creating interfaces that allow education to reach the underprivileged.” (Pearson online, 2016)

In narrowing our interest, here are a few inspiring examples specifically related to refugee and immigrant Newcomer educational services. Canada’s Southwest Newcomer Welcome Centre services refugees and immigrants in multiple capacities. Their mission is, “To enable independence and respectful community participation for Newcomers to Canada by providing settlement and integration services in a safe and welcoming environment, and by promoting cross cultural awareness to all in the communities we serve.”

Southwest Newcomer Centre’s Vision is more objective. It calls for the center, “To be a comprehensive newcomer service providing agency acting as a gateway to equitable, respectful, welcoming communities where all members are empowered to actively participate and contribute.”

Austin, Minnesota is a refugee hub with a thriving Newcomer Welcome Center. It also has a clear mission statement: “The Welcome Center serves the City of Austin as the community’s multi-cultural center, building community by welcoming newcomers, supporting residents in transition and creating access and opportunity.” Austin’s vision holds that, “The Welcome Center envisions a vibrant and culturally diverse community where everyone is accepted, respected and independent.”

HOW DO WE CREATE OUR OWN M/V STATEMENTS?

First, gather your team. Mission and vision objectives are not one-man (or woman) shows. Make room for ideas to circulate. Open the floor. Disagree. Break thinking down and re-configure it. Decide what’s best for your team. Then, decide what’s best for the population you serve and override the interests of the team.

This is a time for finding your organization’s core. All outward momentum will come from this center, so be sure it’s solid. (Or at least, that it is stable enough to bear the weight and stress of the current and future objectives you will set for your organization).

Then, jump in. Here are a few guiding questions as you begin your thinking around mission and vision statements:

· Who are we serving?

· What are the precise demographics of the population that we are serving?

· What do we want to accomplish?

· What do we aim to provide?

· By what means will we accomplish these aims?

· How will our efforts enable student success?

· Why is the student success we defined important?

· How will we measure/determine success?

· How will our efforts better our school and community?

Next, elaborate on your values. What character traits, key ethics or primary goals does your organization consider sacred or essential to program success? How does or will your team maintain its integrity? Values encompass qualities such as leadership, partnership, innovation, safety, continuous growth and improvement, accountability, and professionalism. What does your team stand for?

Now, begin to work together to invent (or revisit) your statements. There is no right or wrong way or any blanket format. Find what works best. You can start big (vision) and bring those ideas into clear, applicable focus (mission). Or, flip the process and move outward toward your team’s vision.

Come back to your M/V statements regularly. To reinforce their importance, begin and end meetings with them, especially in the beginning stages. Remind each other to check in with your team’s core values throughout decision-making processes. Let your mission and vision define your team’s work.

As a Newcomer-focused educational consultant, my professional objectives read:

My mission is to empower educators to provide Newcomer ELLs and all students with the tools, resources and support they need to achieve their highest academic and social capacity.

My vision is that all learners have an equitable right to high quality education and upward social mobility. All learners possess an ability to achieve greatness. All educators have an equitable right to training and support that enhances student growth. All teachers are capable of instructional excellence.

What is your team’s mission and vision?

10 Vocab Strategies for ELLs (and all learners!)

Vocabulary Strategies

Vocabulary development is an important component of language acquisition. If you’re ready to explore new strategies, jump into any of these. They are teacher tested (self-included!), cross-curricular and can be modified to suit all grade and language levels. Best of all, each strategy is low-prep and places students at the center of their own learning- which is exactly where we want them.

4-PLEX

This activity encourages vocabulary development, especially that which builds throughout a unit or text. Students draw a set of perpendicular lines on a paper to create four equal segments (or fold a piece of paper into fourths).

In the upper left section, students will write a vocabulary word. In the upper right quadrant, they will illustrate the word. The lower left section will contain a sentence with the vocabulary word underlined or highlighted. In the last quadrant, students will produce a definition.

Older students may create smaller versions of this exercise in a personal notebook, with multiple 4-square organizers per page. Alternatively, students can work to complete these organizers in groups of 2 or 4 to encourage cooperative talk and collaborative skills.

CAPTAIN

This activity allows students to study content vocabulary and practice speaking and listening skills in a fast-paced game format. Begin by dividing the class into two teams. Arrange teams so that all but one student from each group is facing a whiteboard or Smartboard. Position two chairs (one for each team) so that they face the members of their group, with the backs to the whiteboard or Smartboard.

One student from each team sits in the chair so that he or she can see their teammates, but not the writing space. He or she is the "captain". The remaining team members form a line facing the chair. The facilitator records a vocabulary word from a familiar unit of study on the board. The student at the head of each line aims for the captain to name the correct response without actually saying, drawing, or spelling the target word. The team whose "captain" says the word first gets a point. Line leaders from both lines move to the end of the line and the next student steps up, repeating the process.

Once all students have described a word to the captain, the chairperson moves to the end of the line and the line leader becomes the next captain. This process repeats until all vocabulary words are used.

CLOSED SORT

Closed sorts allow students to process new information and vocabulary in a guided, structured way. Sort decks can be made ahead of time, and for very young learners this may be ideal. Generally, it is best to have students create their own sort decks as a means of practicing reading and writing skills. Sorts can be completed independently, but partner work is even more beneficial in that it encourages collaborative problem solving and exercises listening and speaking components. To create sort decks, students can use a class generated list, personal dictionary or unit vocabulary wall to write individual vocabulary words on index cards (or halved index cards).

In a closed sort, the facilitator clearly defines the sort groups for students in advance. For example, an animal sort might include the categories: mammal, reptile, bird, fish, amphibian. An earth sciences sort might include the categories: rock, mineral, fossil. Students work to organize their cards in alignment with the pre-determined categories. Students’ work should be validated by a teacher, textbook or pre-made answer key.