Mitigating Student Trauma in the Virtual Classroom

The most common question on deck these days: How do I go about minimizing student trauma in the virtual setting?

Of course, this is a loaded question. So let’s start by laying a foundation. Here are the most practical ways to get started (or to boost your existing trauma-informed practice).

Reframe the conversation: Mitigating trauma isn't about fixing broken things. It's about restoring power. The distinction is critical. This power belongs to our students, and they’ve owned it all along. Sometimes it gets interrupted. We can see ourselves as technicians, trained to employ tools that can help to get the power-up and running again. The next step: turn those Power Restoration tools over to our students.

Get Brainy: Don't underestimate the power that comes from understanding the human brain. Set aside the time. Open the conversation. Invite students to become observers of their own thinking (metacognition). Practice non-judgmental recognition of fight-flight-freeze-submit responses. Experiment with trauma minimizing strategies in a safe space to discover 'just right' fits.

Resources:

Elementary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H_dxnYhdyuY

Upper Grades Parts of the Brain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5CpRY9-M

Upper Grades Fight-Flight-Freeze: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rpolpKTWrp4

Elementary Journal: What Survival Looks Like for Me (Inner World Work): http://www.innerworldwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/What-survival-looks-like...-for-me-3.pdf

Upper Grades Journal: What Survival Looks Like In Secondary School (Inner World Work): http://www.innerworldwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Survival-In-Secondary-School.pdf

Practice Predictability: YOU show up day after day. Remember that this seemingly simple act goes a long way in minimizing the impacts of trauma for our students. The consistency of your presence and the routine you strive for in daily learning is critical. Preemptively signal upcoming changes, where possible. Predictability fosters trust. Trust lends itself to safety. And when students feel safe, they are able to learn.

Host a Restore Your Power Space: Create a space or folder in whatever virtual platform you're using. House Power Restoration tools here and encourage students to visit, even when school's not in session. Digital black-out or magnetic poetry, drawing/sketchnoting tools, guided bilateral movements, and SEL-based calming strategies are all good fits here. Looking for more resources and strategies? Explore our blog and stay tuned for our upcoming book on this topic with ASCD (due early 2021).

Resources:

Mitigating Transition Shock in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Settings. Louise El Yaafouri (DiversifiED Consulting) and Saddleback Education: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E9KxIFECSF8

Edutopia: Strategies for Easing Transition Shock by Louise El Yaafouri (DiversifiED Consulting) https://www.edutopia.org/article/strategies-easing-transition-shock

Art Therapy ideas: https://diversifi-ed.com/explore/2018/10/1/art-therapy-for-trauma-in-the-classroom

Recommended at-home resource: http://www.innerworldwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/What-Survival-Looks-Like-At-Home-Quick-Printout.pdf

5 Tenets of Teacher Self-Care (and the mistakes that helped me discover them)

Image Credit: Shutterstock

Here it is: we are not superhuman.

Educators, as an occupational whole, tend to submerge this truth. We ignore it, push it away, and look the other direction even as it sinks down into the recesses of our thinking.

And so, we educators require frequent reminders of our vulnerability- and more than that, encouragement that our humanness is a spectacular mark of endurance, bravery, and triumph. After all, we’re living the process: trekking the course, failing forward, making small (and giant) moves toward success. Heck, we’re shaping spectacular generations of tiny humans and young adults.

Isn’t that enough?

One might think. We might think. So, how are we such experts at forgetting our own freaking fabulousness?

Ladies and gents, it’s time to turn a page, to support one another, and to make it a movement. We owe ourselves some delicious self-appreciation. We need to be reminded that perfectionism is not our ally in teaching. In fact, sometimes a bit of disaster or delay or detour is its own kind of perfect. Sometimes, these are healthy indicators that authentic learning is taking place.

We didn’t sign up for a competition of Pintrest-y brilliance or TPT worthiness. We signed up to grow young people into decent, well-rounded adult human beings. How can we possibly expect that process to be neat and tidy? Anyone have completely a drama-free kiddo out there? ‘Cause I’ve never known one. In any event, why would we want a totally systematic, predictable standard for education? Sounds pretty dull (and not particularly effective).

On this rant about perfection: what is it exactly that we’re aiming for? Who are the chosen few who get to decide what that is or what that looks like? Show me a perfect textbook, a perfect curriculum, a perfect approach- and I’ll show you fifteen people ready to argue against it. So again, where are we going with this whole ‘be the best’ race?

The best is us, teachers. Right now, as we are and as we are growing to be. And damn it, we’re not the kind of perfect that rubrics were made for.

So we’ve got to give ourselves some grace. We’ve got to let the sweat run down our cheeks without being embarrassed about it. This business that we’re in requires effort. A ridiculous amount of it. Sometimes it overwhelms us. And that’s ok. (I know I’m not the only one to fight back- or fail to fight back- some super sneaky tears in the classroom.)

When we follow the good advice of putting our own oxygen masks on first, our students are the beneficiaries.

Let’s start simply, by embedding these simple practices into our daily craft:

1. Do unto yourself as you do unto others.

How are we inclined to talk to our students- with sarcasm and criticism or with kindness and encouragement? How do we view our students- from a deficit lens or an asset lens? How do we define our students’ success- by a narrowly prescribed definition or according to gains along a personalized growth trajectory?

Yeah, we know the response. We’re educators, right? So, let’s turn it around on ourselves. Imagine: What if we talked to, reacted to, and supported ourselves in the same manner that we do our students?

This is harder than it sounds. We’ve trained ourselves into becoming hypercritical of our teacher-self-worth.

Stop.

What did you survive today? What went incredibly right? How has your craft improved over the last year, month, or week? Whose morning did you turn around with a hug, smile, or kind word? Who did you potentially spare from a not-so-great decision?

Take a few moments to celebrate you. Check yourself in your self-talk. Would you say this to your student? Reframe, rephrase, and fill up your cup. You’ve earned every last bit of it.

2. Embrace collectivism.

Like it or not, folks, we’re in this together. My favorite Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. quote: “We may have all come on different ships, but we’re all in the same boat now.”

Sisters and brothers of our craft, we’re going to be spending a lot of time together. So, seek out people that you want to be on this ride with. Who makes you excited about your role and the work that you’re doing? Who’s your venting ear? Who’s the cheerleader? The joker? The advice-giver? The walking ELD standards encyclopedia? The mentee under your wing?

Find and foster these relationships. You don’t have to be besties outside of school. Shoot, you don’t even have to have each other’s phone numbers (although that’s fun, too).

Then, put yourselves on the same team. You’re all going for one goal- student success. Everybody on the team has a role, which is to meet students where they are from his or her unique vantage point and with his or her unique set of tools. Each person is necessary to the others in the aim of achieving the goal.

In this context, competition is irrelevant. Not only this, but it can also compromise the team’s ability to reach the goal. Leaning exclusively on neatly-packaged curricula also loses its meaning. We are the tools we need to reach and teach our learners. The textbooks and Google slides and lesson plans and Zoom sessions aren’t the master plan- they are supplementary materials.

Learn about your teammates’ strengths. Instead of aiming to outdo their efforts (guilty as charged), learn to leverage these assets in building consistency and getting through to kids. Ask for a shared sub day and spend an hour in one another’s classrooms if you’re able. Allow a few minutes within team planning time to just be present in cultivating relationships. You might look outside of the building, too. Twitter is a great place to expand your professional learning network and maybe even discover a few new members of your clan.

Also, don’t be an ass. Your tribe doesn’t need it, and neither do you.

3. Set down the assessments (just for a minute).

Here are a few bright spots in my teaching career: I consistently had the lowest standardized testing scores of all same-grade classrooms at our school over a nine-year period, and I was barely rated an “Approaching” level teacher six years into my practice.

Ok. Let’s talk about this. Those low scores- 100% of my students each year were refugee and immigrant newcomers. Heck no, they weren’t able to keep up on those tests (*at first…but watch them soar now). “Welcome to America, kids... here’s your test.” Then, the digital assessments came around. Jiminy, half of my kids had never used a desktop in their lives. The first thirty minutes of an online test is an exercise in how not to sword fight with a computer mouse.

You know what those tests didn’t show (or at least, didn’t make room to celebrate)? Growth. Like, crazy out of control multi-year gains in nine months kind of growth.

How about those teacher evaluations? Three weeks before that mediocre evaluation I was rated “Effective” by a different district evaluator. And two weeks after the “Approaching” mark (which I cried and whined to my tribe over), another administrator found me to be “Distinguished” (the highest-rated evaluation score in our district).

So, which one am I? Best guess... probably somewhere in the middle, leaning toward pretty freaking good. I mean, I sure didn’t jump the scales of expertise in 2 weeks- and I probably wasn’t as ineffective as I’d led myself to believe after that ‘off’ evaluation, either.

Here’s the deal: assessments and evaluations are what we make of them. Do we learn something? Do we make a plan to improve and grow? Great.

Should we give away our power to them and let them stress us out? Nope.

We encourage our students to see their self worth as something that is independent of an isolated data point (or any other statistic, for that matter). Dear educators: if we’re going to pull that equity card, then we’d better start making room for ourselves in that grand philosophy, too. Um, are you listening in on this, too, admin? That also goes for what we put on our Ts.

4. Maintain high expectations, but lower the risk.

Here’s another one we practice with our students, right? We know that in order to enable our learners as positive risk-takers, we need to:

Create an environment of safety and trust;

Offer choice and support; and

Not make it a super freaking scary thing to do.

So where’s the self-love?

Again, let’s go back to how we treat others. How do we make leap-taking a little less intimidating for our students?. We provide high yield opportunities in low-drama settings. We encourage multiple means of demonstrating proficiency. (What works in one class setting may not be what my newcomer students- or what your kiddos- need right now.) We model cooperative learning and constructive conversation... including those talks with the ol’ self.

We, teachers- we’re great at a lot of things. Self-care isn’t usually on that list. It’s like it’s part of the standard educator’s playbook: students first = self last.

No and no. Take that page out. Burn it. Start a new story.

Yes- hold yourself accountable. Do aim for greatness. But damn it, give yourself some freaking wiggle room. Wrap your own anticipated growth up in the same fabric of fun and curiosity that you would for your students. Anxiety should not be a badge of teaching honor.

5. Recognize discomfort, but don’t let it define the situation.

Quick story: Long ago, in my first year of teaching refugee newcomers, I had the brilliant first-day-of-school idea to sit eight students from Myanmar (Burma) together at the same table so that they could “help each other out”. How’d that work out for us, you ask?

Well, it didn’t. The eight students spoke five different languages and came from six distinct cultures. They were also at literal war with each other in the real world.

Talk about a hitch in the classroom-management flow. But here’s the thing: we got through it. We eventually adjusted, learned some new ways of coping, adopted a few healthy communication tools, and had a really awesome year. Some of those nine-year-olds even became viable bridges between the tribes that existed in their own apartment communities.

That discomfort was like a fertilizer for our growth. And, of course, the best fertilizer is a pile of... super smelly business.

Let’s not sugar coat the situation. Our work is hard. Like, really freaking hard. Some moments are rougher than others. Some days we come up short. And sometimes, there’s not a dang thing we can do about it.

But did we go back into the ring?

If the answer is yes, stop there. That’s the game-changer.

Thanks, educators, for doing what you do: for showing up for our kids, for creating safe spaces, for co-constructing our collective futures. Now, go take care of yourself for a minute, will you?

You deserve it.

8 Ways to Optimize a Learning Culture... and Celebrate Diversity

Culture. It’s the latest education buzzword to catch fire, and it is applied to a seemingly endless range of affairs. We refer to our students’ heritage cultures. We toss around the idea of a school culture, a classroom culture, a staff culture. So, what exactly are we talking about here? In the simplest possible terms, we can look at it in this way:

“Culture is the way you think, act and interact.” –Anonymous

From this lens, it is indeed possible to reference "culture" across such a variety of social platforms. How our students think, act and interact at home and in their communities is a reflection of their heritage culture. How we think, act and interact at work is a reflection of our work culture.

Let’s consider our schools and classrooms from this same vantage. Looking to the best versions of ourselves and our programs, what do we envision as an optimal learning culture for our students and staff? How are we encouraged to think, act and interact with our students and colleagues? How are we teaching learners to engage with each other in affirmative ways?

As a school or classroom leader, these are important thoughts to map out. My ideas may not look the same as your ideas. That’s ok. We can lay some common ground, though. The following cues present an opportunity to check in with your own vision of school culture. How can you help to improve the way that your team thinks, acts and interacts?

1. Invest in Students

We all ache to know that someone we care about is standing firmly behind or beside us. If our aim is to increase a student's success rate, our honest investment in both their present capacity and future potential is non-negotiable.

Express a genuine interest in each individual. Learn how to pronounce student’s names correctly and begin using them on the very first day. Ask questions about students’ heritage culture and allow for safe opportunities to share these insights with other classmates. Offer relevant multicultural reading materials. Post flags or maps, and have students mark their heritage country. Be a listener. Find out what students find interesting. Commit to supporting students with time-in over time-out. Show up. Keep promises. Practice being present and mindful with students. Nurture connectivity.

2. Provide Choice

When presented with choice-making opportunities in a safe, predictable environment, learners develop self-efficacy and strategizing abilities. We can scaffold these processes to enable students to grow as wise decision makers. Begin by limiting the range of available options. Model reasoning through active think-alouds.

Also, it is important to allow time for students to consider and process potential gains and sacrifices involved when choosing between items or activities. Similarly, prompt students to predict the probable consequences of unwise choice making and to reflect on these outcomes when they occur. Incorporate choice making throughout the day. Station (center) activities, choice of paper color, homework, reading book, order of task completion and game selection are manageable places to start.

When students are invited to make healthy choices- and have opportunities to practice doing so- they are much more inclined to become invested, engaged learners.

3. Provide Clarity

Students, not unlike adults, desire to know what is expected of them. Who doesn't enjoy a road map to success? By sharing bite-sized road maps with your students throughout a school day or school year, you are helping them to succeed. “Bite-size” can be defined as 3-5 clear steps, with a target of three.

As we’ve already mentioned, clarified expectations foster routine, predictability and ultimately, a sense of safety. Be sure that instructional objectives are posted and communicated. Is your class schedule visible and correct? Do you refer to it throughout the day? Are station areas and supplies labeled (using rebus indicators, where necessary)? How often do you review key routines? Check your day for clarity. Define and refine.

4. Trust

Trust that students are wholly capable of making great choices and doing the right thing. Does that mean perfection? No. It does mean that in a healthy, facilitative environment most students, most of the time, will strive to meet the expectations set by (and modeled by) the teacher. We are intentional about setting the bar high, because that’s where students will reach. Maintain confidence that they will stretch to achieve it.

As students see that you trust them, they will begin living up to the expectation that they are probably doing the right thing. They will almost always respond by trusting you in return. Aim for autonomy. Give away power (when appropriate). Expect greatness.

5. Practice Problem Solving

Investigation that relies upon solution seeking engages students in developing deeper concept understanding and creative thinking abilities, while also building essential life skills. Problem-solving behaviors are learned. They are either explicitly taught or modeled by others. The school is an ideal incubator for nurturing these attributes.

Offer specific steps toward solving a problem. Model these thoughts and behavior patterns. Provide multiple opportunities for students to practice problem solving in a variety of subjects and contexts. View problems as “puzzles”. Solution seeking is a willed behavior. Our role is to guide the discovery of enjoyment and creative thinking in these processes.

6. Teach Critical Social Skills

Young people often need to be taught how to interact in positive ways. This is especially true in a Recent Arriver context, where layers of cultural expectation overlap often one another. Essential social skills encompass sensitivity, empathy, humor, reliability, honesty, respect, and concern.

Learners often benefit from explicit step-by-step social routines that work through these skill sets. Modeling, play-acting, and “Looks Like/Sounds Like/Feels Like” charts are also useful. Plan lessons to incorporate openings to explore and practice social skills. Offer guidance, and get out of the way. Provide cuing only when relevant. Share constructive feedback and reinforcement of positive behaviors.

Be the way you wish your students to behave.

7. Embrace “Failure” as a Success

Trying requires immense courage.

Perceived failure is a byproduct of trying. If we look at a FAIL- a First Attempt In Learning, then we are able to see that we have many more possible tries ahead of us. When we work to remove the fear of failing, we are also working to embed a confidence in trying.

Try celebrating failures outright. “Did you succeed the way you hoped you were going to?” No. “Did you learn something?” Yes. “Bravo! You are a successful learner.” Next time you fail at something, try acknowledging it in front of your students. Observe aloud what might have occurred and what part of your strategy you might change to bring about a different result. Failure is simply feedback. If we can take some wisdom from it, and adjust our sails, failure is a sure step in the right direction of success. Aim to create safety nets for trying.

8. Acknowledge Progress

A simple acknowledgement of our gains can go a long way. When we feel appreciated in our efforts, we also feel empowered to continue on a positive trajectory. Administrators, teachers, bus drivers, custodians, cafeteria personnel and after school care teams perform better in supportive environments where they feel that they are a contributive factor to the overarching success of a network. Our students, not surprisingly, also thrive in these settings.

Progress has an infinite number of faces. Growth and change can occur in every facet of learning- in academic, linguistic, social, emotional and cultural capacities.

Take the time to offer a thank you for a student’s concentrated efforts. Post students’ work, along with encouraging and reflective feedback. Share students’ growth. Acknowledge healthy choice making, positive social behaviors and persistence in the light of adversity. Help all learners to discover, refine and purposely engage their strongest attributes, and seek equity in endorsing successes publicly. Each day, relish in small miracles.

Teaching Resiliency: A Tool Kit

Resilience is the ability to negotiate and recover from adversity. Humans experience all kinds of unique life experiences that demand an element of resiliency in order to move forward. We may endure physical illness, family dysfunction, abuse, transition, migration, loss or defeat.

We are also hard-wired with tools to overcome these events. We add to this tool box of healthy coping mechanisms as we move through life. We experience significant events that require us to manage defeat and rise again, and we also observe resilient-oriented behaviors of others who pass through struggle.

Sometimes, our ability to overcome adversity becomes compromised- perhaps our systems have become overwhelmed by challenge or we have not had access to healthy examples of resilience (or we have noted plenty of examples of unhealthy coping behaviors). Because resiliency is largely learned, students can benefit from lessons that explicitly teach and allow for practice of resilience-oriented behaviors.

In speaking to a school-based approach to resilience, I find it helpful to examine the concept from four lenses: foundation, regulation, incorporation and education.

Foundation

Foundation, in the context of achieving resilience, relates to the meeting of basic needs. Access to essential goods and services such as healthy food, clean water, clothing, transportation and medical care are considered foundational to resilience. Other features of resilient children include a sense of safety and “access to open spaces and free play”, which enriches multi-faceted age-appropriate development (1). Discrimination plays a role in determining a baseline for resiliency, too. As incidences of prejudice, discrimination and bullying are decreased, resilience is encouraged.

Regulation

Resilient individuals are capable of self-regulation. That is, they have developed healthy ways to negotiate and recover from unexpected or undesirable life events. (4) Healthy regulation mechanisms include self-soothing, creative problem solving, acknowledging and keeping boundaries, practicing bravery, calculated risk-taking, asking for help, flexibility and exercising a sense of humor when things don’t go as planned.

Incorporation

A sense of belonging, or “feeling valued and respected within a community”, is critical to resilience. (3) (4) Children, in particular, need to be able to identify specific people and places that make them feel welcomed and protected. Positive recognition and inclusion are critical tenants of belonging. (3) Positive relationships matter, and a diversified portfolio of relationships is ideal: family members, school friendships, non-school friendships, teachers and mentors. (1) Research indicates a a robust support community- and a deep sense of belonging within that community- are strong indicators for resilience. (2)

Education

Resilience can impact student learning; and learning can influence resiliency. Those who have their basic needs met and belong to the learning community- are more receptive to receiving and storing new information. Similarly, students may gain confidence through learning and sharing existing strengths, which promotes resilience. (4) Many indicators for resilience are embedded throughout the school day: organization, relationship building, access to play, opportunities to share expertise, and practicing commitment and follow-through.

From each of these four lenses, let’s explore some ways that we can actively approach resiliency and engage students in resilience-oriented behaviors at school.

FOUNDATION

Students cannot learn when they do not feel safe. Similarly, they will struggle to process new information after a poor night’s sleep or missed breakfast. Those who are facing social challenges, such as discrimination or bullying, may find it impossible to concentrate on the learning at hand. So, before we address the curriculum, we must address the learner. How are our students showing up for each learning day? How can we encourage those students who come to school in survival brain move toward learning brain… and stay there?

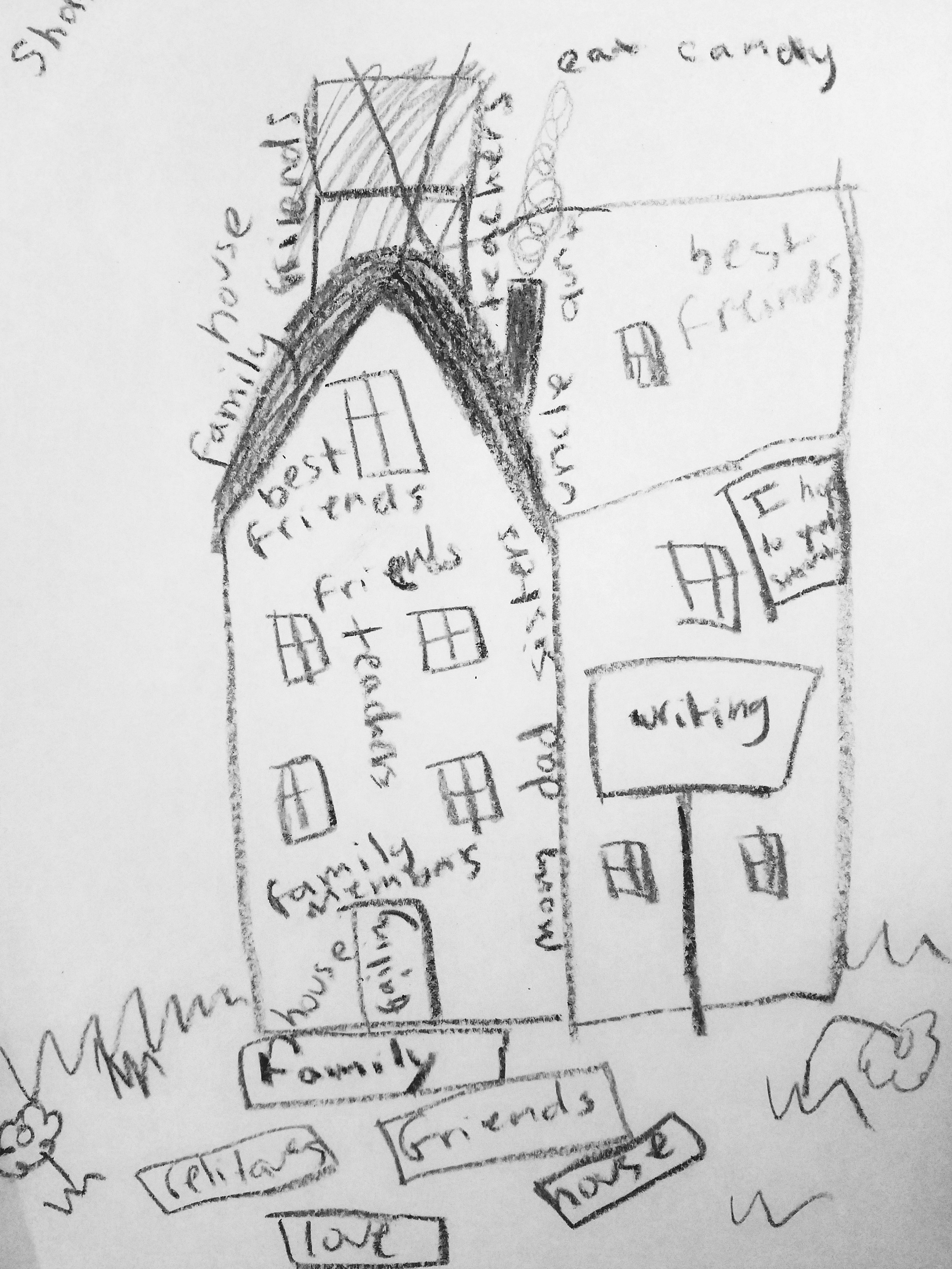

One of my favorite activities is the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, or DBT House. You can visit the activity description and view students samples HERE. The strategy is also available in the book, The Newcomer Fieldbook (Louise El Yaafouri), available HERE.

The DBT House exercise allows a glimpse into students’ lives, so that we re better able to meet them where they are. To foster resiliency, I like to follow the DBT House with this “Being Safe” lesson from Resilient Tutor Group: View it HERE.

PROMOTING ACCESS TO BASIC NEEDS AT SCHOOL

· 7 C’s of Resilience VIDEO

ANTI-BULLYING AND BULLYING PREVENTION

Non-academic foundations for learning:

· K. Brooke Stafford-Brizard @ EdWeek

REGULATION

Self-regulation leads to resiliency. Most self-regulation behaviors are learned. With this in mind, it makes sense to incorporate and model effective regulatory strategies throughout the school day. Chances are, we do this already. We may ask a student to count to 10 slowly before reacting; to self-evaluate and record distress levels; to identify “safe” spaces in the school or to diffuse disagreements with a Peace Circle.

Here are a few of my favorite techniques to use with learners of all ages.

Check out these other worthwhile resources, too!

· American Psychological Association

INCORPORATION

There are many ways to encourage students to grow in their sense of belonging at school. A great way to begin is by deliberately focusing on simple cues of belonging, such as making eye contact and referring to each child by his or her preferred (and correctly pronounced!) name. The following lessons and tools provide an entry point to promoting healthy incorporation in a school setting.

· MindSet Kit LESSONS

· MindSet Kit INTERACTIVE

EDUCATION

How can we draw from students’ existing resilience? How do we make room for bolstering new strands of resiliency in our already congested school day? We can begin by choosing resilience-building strategies that can be easily incorporated into a lesson and into the daily functioning of a classroom. Examples include:

· creating and adhering to routines (as much as possible!);

· opportunities to practice responsible choice-making (hey-hey, flexible seating!);

· brain breaks that engage students in physical exercise and creative play (GoNoodle is the bees knees!);

· learning games that encourage memory and impulse control;

· encouragement to practice safe risk-taking;

· and modeling of resilient behaviors, such as reframing disappointment.

As these tools and expectations become consistently embedded throughout students’ school experiences, they become part of the culture of the school. Ready to get started? Check out these recommended launch-points:

OVERALL TOOLBOX:

EFFECTIVE STRATEGIES FOR ACKNOWLEDGING FUNDS OF KNOWLEDGE

· North Carolina Early Learning Network

EXECTUTIVE FUNCTIONING STRATEGIES FOR STUDENTS:

· Career and Life Skills Lessons Channel VIDEO

LESSON PLANS & IDEAS FOR RESILIENCY:

Sources:

1. Pearson, Umayahara and Ndijuye. Play and Resilience: SUPPORTING CHILDHOOD RESILIENCE THROUGH PLAY A facilitation guide for early childhood practitioners

2. Sarah V. Marsden, Resilience and Belonging https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-55019-4_4

3. Taylor & Hart. The Resilient Classroom A Resource Pack for Tutor Groups and Pastoral School Staff, Published by BOND and YoungMinds.

4. Nowicki, Anna. 2008 Self-efficacy, sense of belonging and social support as predictors of resilience in adolescents Anna Nowicki Edith Cowan University

Trauma, Stress & Friend-Making

Student trauma and high levels of stress can manifest in a wide range of socio-academic challenges. As one example, complex stress can hinder friend-making. This is especially critical for EL students, as social inclusion an integral component of integration. As we strive to create trauma-sensitive learning environments for all students, we must be inclusive of the need to promote healthy social interaction and friend making.

In looking at refugee Newcomers specifically, here’s what we know: “With no other complications, it may be difficult for resettled refugee children to form healthy peer relationships in the host setting.” (The Newcomer Student, 2016). Let’s look at why.

“Newcomers face challenges in communicating thoughts and feelings in the new language, and may feel that peers do not understand them. As an added complexity, children who demonstrate elements of post-traumatic stress also score lower on the prosocial behavior scale. In other words, normative social efficacy is compromised.” (The Newcomer Student, 2016).

Friend making and self-esteem are inherently linked. Learners who feel that they have friends (or at least are largely accepted by their peers) are more likely to demonstrate healthy self-confidence. The ability to make and keep friends has academic implications, too. Students who self-identify as partners in a friendship or friendships tend to have healthier self-esteems; and learners with this type of confidence are more likely to perform well academically.

The reverse is also true: individuals who are challenged to make friends are also likely to experience difficulties in learning and participating at school. For example, “a child who has difficulty recalling, pronouncing, or ordering words in the new language is likely to experience teasing or harassment. … Teasing, in turn, can lead to shame and silence, and ultimately, to isolation. Such stalls create obvious fissures in an individual’s friend-making capacities.” (The Newcomer Student, 2016)

We know that trauma and high levels of stress negatively impact friend making (and consequently self-esteem, school satisfaction and academic success). We can also acknowledge our responsibility to aid our students in navigating social exchange as a mechanism of trauma informed instruction.

We can begin this work in the classroom using evidence-based strategies. Here’s how to get started.

1. Create safe opportunities for social engagement. Begin with pair groupings (to encourage talk and decrease the chances of a student feeling “left out”). Build up to small group engagement. Initially, schedule short periods of interaction, working up into longer ones.

2. Begin simply, with exchanges around likes and dislikes or recalling steps in a process. Invite students to find similarities in their views or observations.

3. Choose interactive activities that highlight the various strengths of students within the work-social groups.

4. Aim to initiate small group activities on a schedule, so that students can predict and better prepare themselves for interpersonal exchange.

5. During periods of sustained student interaction, listen for areas that individual students appear to struggle with or exhibit discomfort in. Work with individual students to create “social scripts” that can guide them through tricky points in a conversation.

6. Explicitly teach the meaning of facial expressions and body language. This is especially helpful for students coming from cultures where there are discrepancies in communicative gestures.

7. Avoid competitive exchanges. Instead, offer activities that promote teamwork, sharing, friendly game play and routine conversation. Have students leave personal items behind when they enter a partner or group setting, to minimize opportunities for conflict. Slowly incorporate activities that require sharing or taking turns.

8. Provide live, video or other examples of similarly aged-students engaged in normative play, conversation or group work.

9. Create structure, routine and control, but also allow students some choice and the opportunity to demonstrate self-efficacy. Anticipate that students will act in mature ways. Redirect when necessary.

10. Model how to work through conflict or disagreement. Offer sentence stems and allow students to practice these exchanges in a safe, monitored setting.

11. Prepare students to be active listeners. Emphasize the importance of active listening in a conversation. Ask students to engage in a conversation and recall details about what their partner revealed during his or her talk time. Model facial expressions and body language that indicate active listening.

12. Be mindful that some students will require additional interventions. Be prompt in processing referrals for those services. If, after a period of consistent interventions in the classroom, the student continues to struggle in social setting, request the assistance of school staff who are equipped to support the learner at a more advanced level.

Trauma and stress can impact students’ academic achievement and social wellbeing. The ability to establish and maintain friendships is a singular facet, but an important one. We can do our part to introduce tools that help our students to overcome these obstacles.

Keep in mind that our students are brilliant reminders of the resilience of the human spirit. There is always hope to be found here, and that hope is bolstered by implementation of timely, appropriate and evidence-rooted strategies in the learning context.

Art Therapy for Trauma in the Classroom

All children experience stress. In fact, it is natural and normative for young people to encounter stress and learn to process it in healthy ways. Some children experience very high levels of stress, either as an isolated moment of impact or as a period of heightened, prolonged unrest.

Trauma occurs when the experience of stress is significant enough to overwhelm one’s capacity to manage and diffuse it. Not all individuals who experience trauma will exhibit lasting symptoms of distress. Yet for others, traumatic stress can dismantle one’s entire sense of belonging, safety, and self-control.

As teachers, we may witness the effects of childhood trauma in the classroom. Significant stress manifests in a myriad of ways- from speech impediments and frequent urination to disruptive behaviors and excessive organization. Educators are not advised to step into the role of psychologist or student counselor, unless they are explicitly trained and licensed to do so. However, we can do our best to take proactive measures to mitigate significant stress in the classroom setting.

The implications of trauma in childhood can be significant, affecting physical wellbeing and brain development at a molecular level. Specifically, significant trauma is capable of creating blockages, or “stalls”, in the right brain (where visual memories are stored) and in the Brocas area of the frontal lobe (where speech and language processing occur). Meanwhile, the amygdala, which is responsible for recognizing and reacting to danger, becomes hyperactive, leaving the “fight or flight” switch turned on. (Rausch et al, 1996).

Art is widely recognized as one effective means of trauma-informed care. A variety of art forms are employed in therapeutic contexts. Classroom art activities can be used as a component of trauma-informed instruction and may include drawing, painting, drama, music-making, creative movement, sculpting, weaving, and collage-making.

Artistic expression is unique in its ability to bypass speech-production areas in the brain and construct wordless somatic paths to expression. The actual process of art making is a predominately right-brained activity. As the right brain is stimulated and strengthened, left-brain connectivity (the essential link to language acquisition) can begin to repair. Miranda Field, writing for the University of Regina, explains:

“Research has shown that the non-verbal right brain holds traumatic memories and these can be accessed through the use of symbols and sensations in art therapy. Communication between the brain hemispheres can be accomplished through the use of art therapy and may assist in the processing of the trauma (Lobban, 2014).”

Humans retain traumatic memories in physiological and cerebral ways. The use of art in education addresses both facets. Chloe Chapman, for The Palmeira Practice, shares that “using art to express emotion accesses both visually stored memory and body memory, as not only does it enable people to create images, but the use of art materials such as clay and paint can reconnect them to physical sensation.” In fact, research links sights and touch to the amygdala and the processing of fear. When these sensory elements are introduced in safe contexts, the slow relinquishment of trauma can occur. (Lusebrink, 2004)

Art making provides a container for trauma and can promote feelings of safety, security, belonging, grounding and validation. Creative output engages the student in organizing, expressing and making meaning from traumatic experiences. It also encourages the reconstruction of one’s sense of efficacy and and the notion of “being present” in the new context.

Art expression provides learners with the option of creative choice, as well as the ability to process trauma in their own measure- reducing the likelihood of emotional overload. Ultimately, students who are exposed to art as therapy are more likely to reach a place of recognizing and valuing their own existing coping strategies- and becoming more receptive to learning new ones.

Ready to grow on the path of trauma-informed education through art therapy?

Visit the incredible authors and resources below.

1. 101 Mindful Arts-Based Activities to Get Children and Adolescents Talking: Working with Severe Trauma, Abuse and Neglect Using Found and Everyday Objects (Dawn D’Amico)

https://www.amazon.com/Mindful-Arts-Based-Activities-Children-Adolescents-ebook/dp/B01N47I0FI/ref=sr_1_fkmr1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1514483429&sr=8-2-fkmr1&keywords=dialectical+behavioral+therapy+101

2. The Big Book of Therapeutic Activity Ideas for Children and Teens: Inspiring Arts-Based Activities and Character Education Curricula (Lindsey Joiner)

https://www.amazon.com/Therapeutic-Activity-Ideas-Children-Teens-ebook/dp/B00812X6GE/ref=pd_sim_351_4?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=SB2JP3ZDPDZW5VQXHC03

3. Free Video Series: Trauma Training For Educators (ACES in Education)

http://www.acesconnection.com/g/aces-in-education/blog/trauma-training-for-educators-free

4. Essentials for Creating A Trauma-Sensitive Classroom

https://traumaessentials.weebly.com/resources.html

5. The Art Therapy Sourcebook (Cathy Malchiodi)

https://www.amazon.com/Therapy-Sourcebook-Sourcebooks-Cathy-Malchiodi/dp/0071468277/ref=sr_1_cc_1?s=aps&ie=UTF8&qid=1514483721&sr=1-1-catcorr&keywords=The+Art+Therapy+Sourcebook

6. Art Heals: How Creativity Cures the Soul (Shawn McNiff)

https://www.amazon.com/Art-Heals-Creativity-Cures-Soul/dp/1590301668

7. DBT® Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets, Second Edition (Marsha M. Linehan)

https://www.amazon.com/Skills-Training-Handouts-Worksheets-Second/dp/1572307811/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1514484354&sr=8-2&keywords=dialectical+behavior+therapy+skills+workbook

Risk Factors for Newcomer Trauma

Approximately one quarter of the young people in U.S. schools have endured some type of significant trauma. Trauma can occur as a singular paralyzing event or as a period of intense ongoing stress. We can define significant trauma as distress that is impactful enough to overwhelm an individual’s ability to produce and manage healthy responses to upheaval.

Trauma and shock are complex issues, especially with respect to students’ academic participation. It is important to bear in mind that trauma is often multi-layered and can be influenced by a broad range of factors. This helps us to better understand why two individuals who may have experienced very similar profound-stress life events may rationalize that information in vastly different ways. Underlying risk factors can have dedicated implications for both the impact of trauma and the viability of resilience.

Refugee newcomer students are vulnerable to additional risk factors that may impair or restrict an individual's ability to access emotional coping resources. For example, the age at which the trauma occurred can influence the degree of affectedness (preschool and early adolescence are especially critical periods). In The Newcomer Student, we read:

“The degree to which our Newcomer students are impacted by stress can be notably profound. We can assume that most Newcomers will have endured episodes of prolonged stress, as an organic byproduct of abrupt flight. Of course, affectedness presents itself in individualized ways, and it is intensely codependent upon the length and gradation of stressful experience, as well as a string of alternative variables.”

What are those variables?

We can explore some of the most common trauma impact risk factors for refugee Newcomer students in the info-chart below. We can use this resource to increase our own educator awareness around our students’ vulnerabilities. This understanding can be integrated into a whole child approach to trauma prevention and mitigation in the school setting.

By increasing our own awareness into trauma, we are also expanding the breadth and depth to which we are able to service our students. We can commit to meeting our learners where they are now; setting high expectations for their socio-academic achievement; and celebrating with them critical milestones along the way.

Let's embrace this cognizance that episodes of trauma may manifest in our students, but focus our sights looking forward- to our students' overwhelming, captivating resilience. Our learners have a story to tell, but that's not the whole journey. It's just the beginning.