Newcomer / Recent Arriver Classroom Reminders

We’re into the thick of the year. It’s a great place to pause and reflect on our practice so far this school year and how we will grow our students in the remainder of our time together. It’s a great time for Newcomer/Recent Arriver classroom reminders! Here, we’ll look at the non-negotiables.

What would you add? Be sure to share your thoughts below.

FOUNDATION

Classroom culture drives learning. Newcomer students thrive in classrooms that are safe, structured and predictable. In fact, predictability is a cornerstone of positive school engagement. Predictability breeds trust, trust lends itself to safety, and safety opens students up to entertain curiosity, absorb content and practice positive risk-taking in the classroom.

DIRECTION

It is important to lead with a plan and to ensure that the plan supports equitable participation for all students, including students who are new to the English language. Content–Language Objectives (CLOs) are an effective tool for creating a specific language focus (with the purpose of enhancing content accessibility for ELLs). They are widely flexible and can be implemented across all grades/subjects and for any number of ELs in a class. Content–Language Objectives guide lesson planning and ground student understanding throughout the lesson.

PLANNING

In preparing for English Language instruction, there is a tendency to over plan. When it comes to lesson planning, aim for relevance and quality, not quantity. Return to the Content-Language Objectives. Ask: 1. What one strategy will be most useful to my learners in making the key content more digestible? 2. What one strategy will my students use to demonstrate the language objective within the target language domain (reading, writing, speaking, listening)?

Can more than one strategy be implemented? Of course! Just be sure to aim for clarity. If things start feeling jumbled or unclear, return to your one original focus for each question. Our students will always perform better when they know exactly what is expected of them.

COMMUNICATION

It’s important to keep in mind the amount of fo language that students encounter in a given school day. Beyond the conversational language that must be learned to navigate the bus, playground or lunchroom, learners encounter languages within the language throughout the entire school day.

Let me explain. If conversational English (with its slang, reduced speech and media influences) is a tongue, so is the Language of Mathematics. Isosceles, divisor, and equation are not words students are likely to pick up in their informal conversations. This type of (academic) vocabulary must be explicitly taught. And if Math is a tongue, then so is the Language of Social Studies, the Language of Music, the Language of English Literature, and so on.

Our students encounter thousands of words in a day. For ELLs, this can be especially overwhelming. To reduce the language load, we can be intentional about listening to ourselves. How might we describe the rate and complexity of our speech? How can it be modified for clarity?

In short, here’s what we’re aiming for: Speech should be clear, deliberate and unrushed. (Side note: Louder or painfully elongated speech is not helpful.)

EXPRESSION

Language encompasses so much more than just vocabulary. Tone, register, slang, cultural cues, humor, sarcasm, reduced speech, body language, facial expressions, and gestures must all be negotiated in the context of learning a new spoken language. Gestures, or the motions and movements Gestures can be used to enforce an idea but should become less exaggerated with time, as understanding grows. Where possible, normalized conversational gestures are optimal.

PACING

ELLs often require a longer “wait-time” to produce a response. After questioning, allow up to two minutes of unprompted thinking time. If a student is not yet ready, offer cooperative opportunities for production. Partner-Pair-Share, Numbered Heads, or Rally Table are great approaches; and sentence starters can be embedded into any of these strategies. Just be sure that the student who was originally asked does, ultimately, have the opportunity to share his or her response with the class.

APPROACH

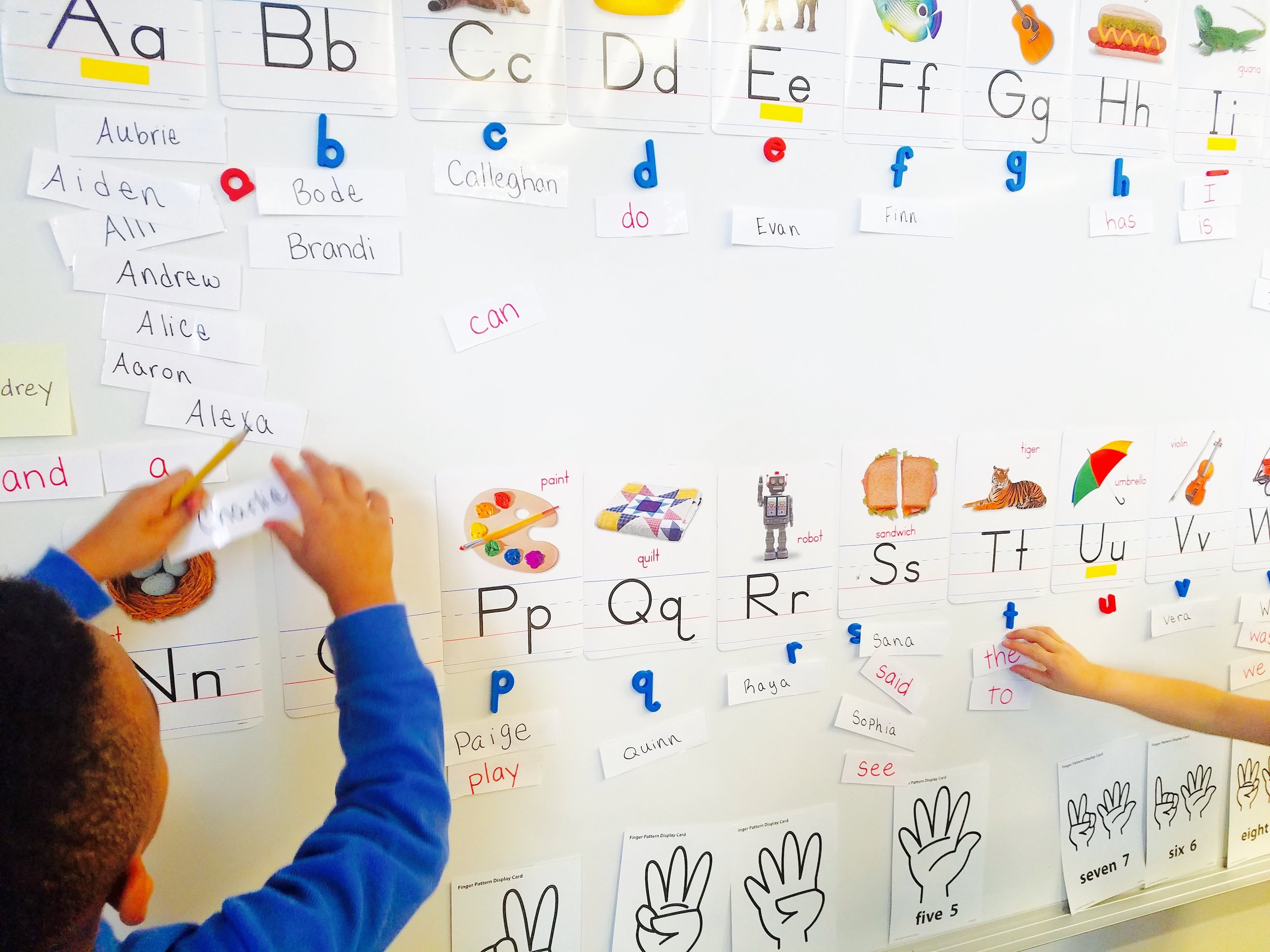

Labeling, visuals, realia, manipulatives, graphic organizers, sentence frames and hands-on exploration are essential to the ELL classroom experience. Each is a language-building path toward content accessibility. Additionally, we can be especially mindful that our curriculum and class reading materials reflect the diverse nature of our classrooms. Where do our students recognize themselves in the school day? How are students invited to express themselves using the four language domains?

PROCESS

Students, including English learners, should have guided agency over their own learning. Work with students to set goals, create viable paths toward these aims, and to monitor their success along the way. Cooperative structures are an important part of this process, as they encourage language development, enhance positive classroom culture and put students in the drivers’ seats of their own learning. Yes, our ELLs CAN meaningfully participate in student-led instruction and Project-Based Learning (PBL). Learn to establish supports… and then get out of the way!

CONSIDERATIONS

Newcomer students may be working through trauma, shock or other stressors. Monitor external stimuli to help mitigate significant stress. Learn to recognize symptoms and know when to ask for help. Work to recognize, celebrate and practice Socio-Emotional Learning (SEL) skills throughout the school day and school year. To build background on newcomer Trauma start HERE. For more tips on trauma-informed care for ELLs (and all students) take a peek at an RC article for Edutopia, found HERE.

INVITATION

You may be a child’s first teacher of their school career, their first teacher in America, or the first teacher to breakthrough. Smile. Show welcoming. Be an example of the possibility that exists for them.

Clarifying Newcomer/RAEL Program Design

Let’s break down some thoughts and areas of confusion around Newcomer/RAEL program design. In serving our new-to-English students, it’s important that our site-based model(s) of instruction truly reflect our student population and specific learning needs.

Clarifying Newcomer/RAEL Program Framework

ELL programming is not a homogeneous application. In fact, there are many different channels to achieve the aim of targeted, accelerated academic language instruction. It will be up to you and your key stakeholders to determine the mode or combination of modes that will best service your specific student population, school culture and available resources.

Both Newcomer or RAEL (Recent Arriver English Learner) initiatives are unique in that they are designated according to units of time. Newcomer and RAEL programming, as defined by ESSA, is designed to serve new-to English speakers for up to two full semesters. After this interval, students are expected to transition into standard EL programming and/or traditional mainstream coursework for the duration of their school career (though even mainstreamed students may still be eligible to receive supplementary English support services).

However, certain exceptions can be made for learners who demonstrate exceptional need. If, after two semesters, a student is not making the appropriate academic progress toward language-based exit criteria- and if such evidence suggests that such gap would significantly impair a child's opportunity to fully participate and succeed in a mainstream learning environment- then he or she may be referred for additional Newcomer services.

Newcomer policy differs from general ELL services (such as ESL for Spanish speakers or ESL pull-out sessions for mainstreamed Newcomers), which are not time contingent. General ELL programming is based on English language skill and ability level. As long as an identified English language learner evidences a need for continued skill-building in any of the four language domains (reading, writing, speaking, listening), he or she will remain eligible for these services.

Let’s take a look at the most common language service programs. Be thinking about which services already exist on your campus, or which specific styles (or combinations) might be the best fit for your campus.

Note that the stated descriptors will widely from one state or district to another. However, the core elements of each program model should remain consistent.

PROGRAM MODELS FOR LANGUAGE LEARNING

Dual Language: Learners are instructed in and encouraged to interact in both the heritage and the host language, with a goal of developing and maintaining proficiency in both. ELA-S (Spanish) programs are the most prevalent form of dual language education in the U.S.

_________________________________

NUMBER OF D/L STUDENTS

_________________________________

PERCENTAGE OF D/L STUDENTS

Transitional Bilingual: Learners are initially instructed in and encouraged to interact both the heritage and host languages, with a goal of developing English proficiency and fully transitioning to mainstream programming. In this way, the heritage language is slowly phased out as English language abilities increase.

_________________________________

NUMBER OF T/B STUDENTS

_________________________________

PERCENTAGE OF T/B STUDENTS

Newcomer Programming: Using Sheltered Instruction techniques and a range of socio-linguistic supports, learners are instructed in and encouraged to interact in English, with a goal of developing English proficiency and fully transitioning to mainstream programming. Newcomer instruction may encompass other areas, including Western norms and values; trauma and shock mitigation; health and wellness protocol and additional parent-outreach efforts.

_________________________________

NUMBER OF N/C STUDENTS

_________________________________

PERCENTAGE OF N/C STUDENTS

Tier 2 ELL/ESL Services: Tier 2 Services enable eligible students to participate in Push-In/Pull-Out resources for English language development, with a goal of enhancing English language abilities after a child has been mainstreamed. In Push-In settings, a language specialist will meet and work with the child in his or her classroom, while Pull-Out options call for students to leave the homeroom for established durations to work on language development in individual or small group contexts. Programs will vary by school design.

_________________________________

NUMBER OF TIER 2 STUDENTS

_________________________________

PERCENTAGE OF TIER 2 STUDENTS

Creating Newcomer ELD Program Mission/Vision Statements

A school district’s mission and vision statements define and guide the work of the educational staff and the growth of the students. These statements are publicly visible, and serve as a pint of communication between central administration, teachers, students, families and community stakeholders. In most cases, districts and schools can also benefit from designing and implementing separate mission/vision statements that are unique to ELL and/or Newcomer programming, but that function alongside and in alignment with overarching district goals.

EL/Newcomer initiatives that operate with clear, program-focused mission/vision statements are able to set goals, monitor progress and make critical decisions to promote socio-linguistic growth of its diverse populations. Great! So, where do we begin?

The answer is, we begin where you begin. You- your school or organization- will begin this journey at a unique map point. You may model yourselves after other successful programs; and later programs may follow your lead. But, your school cannot walk step-in-step with another Newcomer-ELD education initiative.

Why? Your school is not the same as any other school. Your specific student demographics are unmatched.

Your team of educators- their personalities, strengths, opportunities for growth- are exclusive to your campus. Your team’s vision and goals and daily protocol are your own. Your children- the ones who stop to hug you on the way to the office, the ones you call to by first name for moving too quickly down the hallway, the ones you visit with in their homes on the weekends- these are your kids.

Who knows your students and their needs best? You do. Who knows the capacities and limitations of your space, resources and funding? You guessed it.

Your task is to craft- that is, to design and refine- successful Newcomer-ELD mission and vision statements that work for your organization, based on your particular set of ambitions, goals, needs and available resources.

DEFINING MISSION AND VISION STATEMENTS

Mission and vision statements are cornerstones in determining your group’s purpose and function. These declarations help to ground and guide your team as a unified organism with a clearly defined cause. Mission and vision statements are more than formalities. In the case of Newcomer-ELD programming, they serve as a map that guides us, instructionally, in the direction of culturally-responsive EL student growth.

Once they are established, they also serve as a baseline rubric for evaluating all decisions and outcomes. Your team can ask, “Does this item align with our mission and vision? If not, how can we effectively adjust or release it?”

Your mission statement defines what your group aims to accomplish in the present context- right now. The goals outlined in the mission declaration should be realistic and attainable. The vision statement outlines your team’s long-term objectives or ideals- your vision for the future.

Let’s look at some broad examples. Here’s Google’s mission statement: “Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. Their vision statement is “to organize all of the data in the world and make it accessible for everyone in a useful way”. (Google online, 2016)

Google works to organize and make information accessible right now. Organizing data for the entire world is a lofty objective that will take time, but could actually be accomplished at some point in the future.

Mission and vision declarations do not need to be complicated. In fact, simplicity is best. Ikea’s current mission is to “make everyday life better for their customers”. Current is emphasized because mission statements can be utterly static and should be revisited frequently as the team’s success or understanding progresses.

Meanwhile, Ikea’s vision is, “to create a better everyday life for many people. We make this possible by offering a wide range of well-designed, functional home-furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.” The phrasing as many people as possible indicates a long-range goal, or vision, for the future.

I bet you’re thinking, “That’s great, but why are we talking about Fortune 500 companies? We’re trying to get our Newcomer Centers and ELL programming off the ground!” Well, we can approach that very aim with a business-like mind for strategy, organization and anticipated gain (in this case, language acquisition, social integration and academic accomplishment). In this context, mission and vision statements are certainly applicable. Let’s examine some approaches in the educational realm.

Pearson Education details their vision and mission as:

“Our Vision: To fulfill the educational needs across a spectrum of individuals with reliable experience and technology. Our Mission:

· To provide end-to-end education solutions in the K-12 segment.

· To become a leader in the education services field.

· To create comprehensive educational content that can be delivered through a series of innovative mechanisms, thus removing physical and cultural barriers in knowledge dissemination.

· To be a vehicle of change by creating interfaces that allow education to reach the underprivileged.” (Pearson online, 2016)

In narrowing our interest, here are a few inspiring examples specifically related to refugee and immigrant Newcomer educational services. Canada’s Southwest Newcomer Welcome Centre services refugees and immigrants in multiple capacities. Their mission is, “To enable independence and respectful community participation for Newcomers to Canada by providing settlement and integration services in a safe and welcoming environment, and by promoting cross cultural awareness to all in the communities we serve.”

Southwest Newcomer Centre’s Vision is more objective. It calls for the center, “To be a comprehensive newcomer service providing agency acting as a gateway to equitable, respectful, welcoming communities where all members are empowered to actively participate and contribute.”

Austin, Minnesota is a refugee hub with a thriving Newcomer Welcome Center. It also has a clear mission statement: “The Welcome Center serves the City of Austin as the community’s multi-cultural center, building community by welcoming newcomers, supporting residents in transition and creating access and opportunity.” Austin’s vision holds that, “The Welcome Center envisions a vibrant and culturally diverse community where everyone is accepted, respected and independent.”

HOW DO WE CREATE OUR OWN M/V STATEMENTS?

First, gather your team. Mission and vision objectives are not one-man (or woman) shows. Make room for ideas to circulate. Open the floor. Disagree. Break thinking down and re-configure it. Decide what’s best for your team. Then, decide what’s best for the population you serve and override the interests of the team.

This is a time for finding your organization’s core. All outward momentum will come from this center, so be sure it’s solid. (Or at least, that it is stable enough to bear the weight and stress of the current and future objectives you will set for your organization).

Then, jump in. Here are a few guiding questions as you begin your thinking around mission and vision statements:

· Who are we serving?

· What are the precise demographics of the population that we are serving?

· What do we want to accomplish?

· What do we aim to provide?

· By what means will we accomplish these aims?

· How will our efforts enable student success?

· Why is the student success we defined important?

· How will we measure/determine success?

· How will our efforts better our school and community?

Next, elaborate on your values. What character traits, key ethics or primary goals does your organization consider sacred or essential to program success? How does or will your team maintain its integrity? Values encompass qualities such as leadership, partnership, innovation, safety, continuous growth and improvement, accountability, and professionalism. What does your team stand for?

Now, begin to work together to invent (or revisit) your statements. There is no right or wrong way or any blanket format. Find what works best. You can start big (vision) and bring those ideas into clear, applicable focus (mission). Or, flip the process and move outward toward your team’s vision.

Come back to your M/V statements regularly. To reinforce their importance, begin and end meetings with them, especially in the beginning stages. Remind each other to check in with your team’s core values throughout decision-making processes. Let your mission and vision define your team’s work.

As a Newcomer-focused educational consultant, my professional objectives read:

My mission is to empower educators to provide Newcomer ELLs and all students with the tools, resources and support they need to achieve their highest academic and social capacity.

My vision is that all learners have an equitable right to high quality education and upward social mobility. All learners possess an ability to achieve greatness. All educators have an equitable right to training and support that enhances student growth. All teachers are capable of instructional excellence.

What is your team’s mission and vision?

10 Vocab Strategies for ELLs (and all learners!)

Vocabulary Strategies

Vocabulary development is an important component of language acquisition. If you’re ready to explore new strategies, jump into any of these. They are teacher tested (self-included!), cross-curricular and can be modified to suit all grade and language levels. Best of all, each strategy is low-prep and places students at the center of their own learning- which is exactly where we want them.

4-PLEX

This activity encourages vocabulary development, especially that which builds throughout a unit or text. Students draw a set of perpendicular lines on a paper to create four equal segments (or fold a piece of paper into fourths).

In the upper left section, students will write a vocabulary word. In the upper right quadrant, they will illustrate the word. The lower left section will contain a sentence with the vocabulary word underlined or highlighted. In the last quadrant, students will produce a definition.

Older students may create smaller versions of this exercise in a personal notebook, with multiple 4-square organizers per page. Alternatively, students can work to complete these organizers in groups of 2 or 4 to encourage cooperative talk and collaborative skills.

CAPTAIN

This activity allows students to study content vocabulary and practice speaking and listening skills in a fast-paced game format. Begin by dividing the class into two teams. Arrange teams so that all but one student from each group is facing a whiteboard or Smartboard. Position two chairs (one for each team) so that they face the members of their group, with the backs to the whiteboard or Smartboard.

One student from each team sits in the chair so that he or she can see their teammates, but not the writing space. He or she is the "captain". The remaining team members form a line facing the chair. The facilitator records a vocabulary word from a familiar unit of study on the board. The student at the head of each line aims for the captain to name the correct response without actually saying, drawing, or spelling the target word. The team whose "captain" says the word first gets a point. Line leaders from both lines move to the end of the line and the next student steps up, repeating the process.

Once all students have described a word to the captain, the chairperson moves to the end of the line and the line leader becomes the next captain. This process repeats until all vocabulary words are used.

CLOSED SORT

Closed sorts allow students to process new information and vocabulary in a guided, structured way. Sort decks can be made ahead of time, and for very young learners this may be ideal. Generally, it is best to have students create their own sort decks as a means of practicing reading and writing skills. Sorts can be completed independently, but partner work is even more beneficial in that it encourages collaborative problem solving and exercises listening and speaking components. To create sort decks, students can use a class generated list, personal dictionary or unit vocabulary wall to write individual vocabulary words on index cards (or halved index cards).

In a closed sort, the facilitator clearly defines the sort groups for students in advance. For example, an animal sort might include the categories: mammal, reptile, bird, fish, amphibian. An earth sciences sort might include the categories: rock, mineral, fossil. Students work to organize their cards in alignment with the pre-determined categories. Students’ work should be validated by a teacher, textbook or pre-made answer key.

OBJECT-VERB MATCH

The Object-Verb Match activity reinforces the relationship between nouns and verbs. It encourages students to share existing vocabulary knowledge and to explore new language in an interactive context. The activity is best suited for students up to 5th grade and emergent higher-grade learners.

Facilitator uses sentence strips or sticky notes on pieces of butcher paper to post various nouns around the room. As an alternative, images of various nouns (ex: horse, towel, archaeologist) may be posted. *Note: vocabulary that is specifically related to a text/topic of study is suggested.

Students are invited to walk the room, visiting each noun. Learners use the space on each piece of butcher paper to identify and record as many corresponding verbs as possible for each noun posted. Once completed (a timer is recommended), students may be invited to compose sentences using the identified vocabulary, act out the verbs at each station, or discuss contributions in an inside-outside circle format. Examples- Horse: gallop, trot, run, glide, prance, jump, leap, eat, walk, canter, race. Towel: wipe, dry, clean, mop, wring, wash, dry, hang, use, share, spread. Archaeologist: dig, explore, discover, search(ing), examine, think, brush, study, write/record, travel, talk, save/preserve, protect, carry, store.

OPEN SORT

Sorting activities allow students to process new information and vocabulary in a guided, structured way. Open sorts are similar to closed sorts but differ in one critical area. In a closed sort, the organizational categories are pre-determined by the facilitator. In an open sort, students will work independently or in workgroups to devise, define and label their own categories, with only limited guidance from a teacher.

This process encourages critical thinking, rationalization, and problem-solving skills. For this reason, open sorts are best suited to older learners and intermediate/advanced language learners. It is best to have students create their own sort decks as a means of practicing reading and writing skills.

To create sort decks, students can use a class-generated list, personal dictionary, or unit vocabulary wall to write individual vocabulary words on index cards (or halved index cards). Within small collaborative workgroups, learners strategize a rationale for organizing cue cards. *Note: group end products do not need to mirror each other. Groups may be asked to present their sort and rationale to the class. Student work should be validated by a teacher, textbook, or pre-made answer key. For limited proficiency modification, see "Closed Sort" activity.

SYNONYM RACE

Synonym race is a collaborative activity that guides students in exploring similar-meaning words. To prepare for this activity, create identical sets of play cards to be used for groups of students working together (3-5 groups recommended). Cards can be printed and cut or written on index cards. Play cards should contain adjectives that students may or may not be familiar with.

To play, divide students into working groups and distribute a play deck to each group. For each round of playing, facilitator calls out one adjective that is not included in the decks but is a synonym for a word in the deck. (Ex: Silly: Amusing. Interesting: Fascinating. Run:Dash). Groups of students must shuffle through their decks, locate a synonym, negotiate a word (if necessary), and either hold up the selection or write it on a white board. The first group to do so gets a point. Facilitator or a student records all synonym matches in a visible location.

This process continues until decks are exhausted. To close the exercise, students independently write the list of synonyms (and, for upper level students, come up with additional synonyms for each word) into their personal dictionaries, synonym study book, pre-made worksheet or alternative space.

THIEF IN THE MIX

This is an engaging game that allows students to practice the use of verb conjugation while exercising all four language domains. Prior to the start of the lesson, the facilitator creates a class set of index cards with sentence clauses that students will use to construct complete first-person sentences. (Ex: trombone player, last year; dance teacher, 6 years; Lego expert, 4 years old). For early language learners or very young students, sentence stems will be more appropriate.

Pass out index cards to students. Explain that something is now missing from the classroom and that there are a designated number of "thieves" in the class (3-5). The students must now become detectives and seek out the thieves.

To do this, students will need to circulate the room. When they encounter a partner, they have two roles. First, if using a clause card, they must share the detail about themselves. (I have been a trombone player since last year. I have been a dance teacher for 6 years. I have been a Lego expert since I was 4.) Then, the partner records the information in the third person. (He has been a trombone player since last year. She has been a dance teacher for 6 years. She's been a Lego expert since she was 4.) Roles reverse.

When this process is complete, students find a new partner. The game continues for a designated amount of time or through a set number of partners. Finally, the facilitator reveals the details of the "thieves". Those students whose index cards match a description of a thief come forward and read their sentences to the class. As an alternative, all students can practice reading their sentences in an Inside-Outside Circle or similar format.

WORD EXCHANGE

Word Exchange is a strategy that engages learners in all of the language domains. To begin, distribute index cards with vocabulary words written or printed on them. The other half of the class receives index cards with matching vocabulary definitions. Have students read and become comfortable with the cards, offering assistance where needed. Next, students are prompted to circulate the room interacting, exchanging ideas, and problem-solving to match each new word with its corresponding definition.

Once pairs are set (is it wise to have students confirm definition using text glossary, picture dictionary or another resource), they can move to the next step. Partners may compose and display labeled drawings, graphic organizers (such as the Frayer model), songs, or skits to explain the target word. For added linguistic practice, allow each pair an opportunity to present their word set to the class.

WORD RELAY

This activity incorporates kinesthetic engagement as it encourages students to actively demonstrate collaborative skills, content understanding, and sentence building. To begin, students are divided into teams of three to six participants. Each team assumes a “home base” in a corner or side of the room. The facilitator places one deck of cards in the center of the room. This deck of cards contains content/unit-specific words. A second set of cards is placed next to the first. This deck contains sentence building cards, including various prepositions, conjunctions, punctuation marks, and “double underline” cards (indicating the use of a capital letter).

When cued, one person from each team approaches the cards, selects one from each pile, and returns to his or her “base”. This process continues until one team has constructed a full, meaningful sentence, complete with appropriate sequencing and punctuation. Members of the finished team may join other teams as they continue to play until completion.

WORD STRENGTH

Word Strength is best suited for intermediate and advanced language learners. The exercise helps students to better understand subtle gradients in adjectives within like categories. The facilitator's role is to guide students in the process of ordering feeling words from the least to the most exaggerated meaning. This can be achieved in a group or independent context.

To complete the group version on a smartboard or large piece of chart paper, begin with a horizontal line stretching from one side of the workspace to the other. Distribute index cards with pre-recorded target adjectives. In the early stages, it is best to begin with a limited number of cards (3-5), working up to as many as twenty.

Students work collaboratively to organize words on the gradient of intensity. The use of personal dictionaries, anchor charts, contextual text or other resources is encouraged. Example 1: icy, frigid, cold, chilly, lukewarm, warm, toasty, hot, scalding. Example 2: evil, wicked, mean, aloof, indifferent, cordial, friendly, affectionate. The same process can be repeated on a smaller scale for independent work and/or station work.

Ready to dig deeper? These activities (and many others) were created by Refugee Classroom as part of the comprehensive EduSkills platform. Learn more at eduskills.us.

EduSkills is an educational services and school data analysis company serving schools and districts Pre-K through 12th grade. EduSkills collaborates with schools and districts in order to help teachers and administrators become high-performing outcome-based educators with a clear focus on high-level student achievement.

Viewing Heritage Language from an Asset-Based Lens

The following is an excerpt from The Newcomer Student: An Educator’s guide to Aid Transition by Louise Kreuzer-El Yaafouri (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), available HERE or HERE.

ORAL LANGUAGE: THE VOICE OF BELONGING

Language shapes how we think, and the influx of recent immigrants from hundreds of linguistic backgrounds presents a unique challenge to American schools. (1)

Oral language is very often the centerpiece of cultural cohesiveness, as it makes communication possible. Communication, meanwhile, is the foundation of human interconnectedness. Beyond allowing for the rituals of communal exchange, oral language is the primary platform upon which creative expression and universal sense making are constructed. It tells the story of the beginning, the end, and everything in between. It relates the family tree, defines social norms, solidifies romance, and generates war. Our world is made up of words.

All cultures demonstrate a high degree of oral reliance.(2) In certain regions, the communicative aspects of a culture permeate and sustain every grain of social function. In fact, most non-Western languages are rooted heavily in oral tradition. Many cultures are far more reliant upon verbal output and body language than printed text as a means of communicative exchange. Many of our new-to-English students come from these rich oral-centric backgrounds.

In much of Africa, for example, it is common for an individual to demonstrate agility in multiple local and national tongues, even when literacy abilities are restricted. In communities where legal contracts can be accomplished with a verbal handshake, print concepts may be extraneous to successful daily living. Of course, we understand that literacy is nonnegotiable for our students. Still, it may be helpful to understand the utter potency and significance of oral language in the Newcomer setting.

FINDING BALANCE: SUPPORTING HOST-LANGUAGE GROWTH & HERITAGE LANGUAGE PRESERVATION

The ultimate goal of the Newcomer framework is to facilitate English language learning at an accelerated rate, and to prepare students for continued mainstream scholastic and post-school successes. As previously mentioned, one of the best courses of action that we can take in enhancing host language development is to outspokenly value and actively encourage heritage language preservation. While this may seem counterintuitive, research continues to illuminate the benefits of this practice.(3)

The most significant reasons for heritage language preservation have to do with maintaining a coherent self-identity.(4) Moreover, native language acts as a tie that unites families and ethnic communities. When this tie is severed, a sense of belonging is compromised.

A majority of ELLs who are successful in maintaining heritage and host languages also perform better academically than ELLs who are restricted to host language learning at the expense of heritage language.(5) This trend has been documented in standardized testing, as well as in ACTs and SATs. Bilingualism impacts the brain in profound ways, enhancing cognitive function and long-term memory (including the proven delay of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease).(6)

Dual-language skills also enrich problem-solving abilities, promote flexibility and multitasking abilities, and provide for future opportunities with regard to college learning and beyond.(7)

Meanwhile, valuing heritage languages in the classroom encourages tolerance, global awareness, and belonging. Maintaining the host language can also expedite host language acquisition.(8,9) Shawn Loewen writes: “It is important for second language children to feel that their first language and culture are valued and respected. It is particularly important for refugee children . . . to use their first language with other children, their teachers, and at home.”(10)

In the classroom context, we can enable heritage language preservation by allowing our students periods of time where they are encouraged to communicate with linguistically similar students, where applicable, for a short period, and repeating out thoughts in English. We can provide texts representing a variety of cultures and/or languages (see chapter 8 for a multicultural reading list), and we can relay to parents, through a translator when necessary, the importance of maintaining heritage language skills in the home. Through and because of first language fluency, second (or third) language efficacy is more likely to occur.

Welcoming Newcomer Students

The following is an excerpt from The Newcomer Teacher: An Educator’s Guide to Aid Transition (Rowman & Littlefied International) available HERE.

We know that a whole family approach serves our students’ highest learning welfares. We understand that community interest and involvement is a school asset with tremendous payouts. However, such presence is not instantaneous or guaranteed. Instead, it is meticulously cultivated. Who is responsible for this charge? The school and its’ staff. Us.

Strong community relations cannot occur without strong communication efforts by the school. In fact, robust school-to-home communication is an apparent quality of America’s healthiest schools. Positive community outreach disseminates the breakdown of barriers between families and the school and endorses collaboration. Communication is a crux of school success, and it is one that requires support, nurturing, and creative perseverance. (8).

A school can work to foster whole family engagement in any combination of ways. The most common efforts include outreach and inclusion programs. In our classrooms, we also employ home visits, conferencing, parent/guardian correspondence and volunteer/chaperone opportunities. (9).

The same communication tactics are applicable in Newcomer settings. However, they demand significant manipulation and elaboration in order to be successful. The truth is that home communication in multi-lingual, exceptionally diverse school settings doesn’t always go over so smoothly. There are translations, liaisons, caseworkers and older-child spokespersons. There are misunderstandings, misgivings, fears, and discomforts. There are frustrations, question marks, and lines of cultural jurisdiction. There is language, language, and language.

Despite obvious exchange barriers, the roots of parent-school partnership efforts are generally coherent across all socio-economic platforms. In most cases, parents in every category do wish the very best for their children. Similarly, the vast majority of teachers also manifest high hopes and expectations for every single student in their care.

This is the meeting ground. Under optimal conditions, the school is synonymous with safety and collaboration. It is viewed as an action point for trustful collaboration. In the Newcomer setting, this is non-negotiable, as many families may not be aware of or comfortable with Western academic expectations. That’s a big responsibility. We must make the most of it.

Teaching Resiliency: A Tool Kit

Resilience is the ability to negotiate and recover from adversity. Humans experience all kinds of unique life experiences that demand an element of resiliency in order to move forward. We may endure physical illness, family dysfunction, abuse, transition, migration, loss or defeat.

We are also hard-wired with tools to overcome these events. We add to this tool box of healthy coping mechanisms as we move through life. We experience significant events that require us to manage defeat and rise again, and we also observe resilient-oriented behaviors of others who pass through struggle.

Sometimes, our ability to overcome adversity becomes compromised- perhaps our systems have become overwhelmed by challenge or we have not had access to healthy examples of resilience (or we have noted plenty of examples of unhealthy coping behaviors). Because resiliency is largely learned, students can benefit from lessons that explicitly teach and allow for practice of resilience-oriented behaviors.

In speaking to a school-based approach to resilience, I find it helpful to examine the concept from four lenses: foundation, regulation, incorporation and education.

Foundation

Foundation, in the context of achieving resilience, relates to the meeting of basic needs. Access to essential goods and services such as healthy food, clean water, clothing, transportation and medical care are considered foundational to resilience. Other features of resilient children include a sense of safety and “access to open spaces and free play”, which enriches multi-faceted age-appropriate development (1). Discrimination plays a role in determining a baseline for resiliency, too. As incidences of prejudice, discrimination and bullying are decreased, resilience is encouraged.

Regulation

Resilient individuals are capable of self-regulation. That is, they have developed healthy ways to negotiate and recover from unexpected or undesirable life events. (4) Healthy regulation mechanisms include self-soothing, creative problem solving, acknowledging and keeping boundaries, practicing bravery, calculated risk-taking, asking for help, flexibility and exercising a sense of humor when things don’t go as planned.

Incorporation

A sense of belonging, or “feeling valued and respected within a community”, is critical to resilience. (3) (4) Children, in particular, need to be able to identify specific people and places that make them feel welcomed and protected. Positive recognition and inclusion are critical tenants of belonging. (3) Positive relationships matter, and a diversified portfolio of relationships is ideal: family members, school friendships, non-school friendships, teachers and mentors. (1) Research indicates a a robust support community- and a deep sense of belonging within that community- are strong indicators for resilience. (2)

Education

Resilience can impact student learning; and learning can influence resiliency. Those who have their basic needs met and belong to the learning community- are more receptive to receiving and storing new information. Similarly, students may gain confidence through learning and sharing existing strengths, which promotes resilience. (4) Many indicators for resilience are embedded throughout the school day: organization, relationship building, access to play, opportunities to share expertise, and practicing commitment and follow-through.

From each of these four lenses, let’s explore some ways that we can actively approach resiliency and engage students in resilience-oriented behaviors at school.

FOUNDATION

Students cannot learn when they do not feel safe. Similarly, they will struggle to process new information after a poor night’s sleep or missed breakfast. Those who are facing social challenges, such as discrimination or bullying, may find it impossible to concentrate on the learning at hand. So, before we address the curriculum, we must address the learner. How are our students showing up for each learning day? How can we encourage those students who come to school in survival brain move toward learning brain… and stay there?

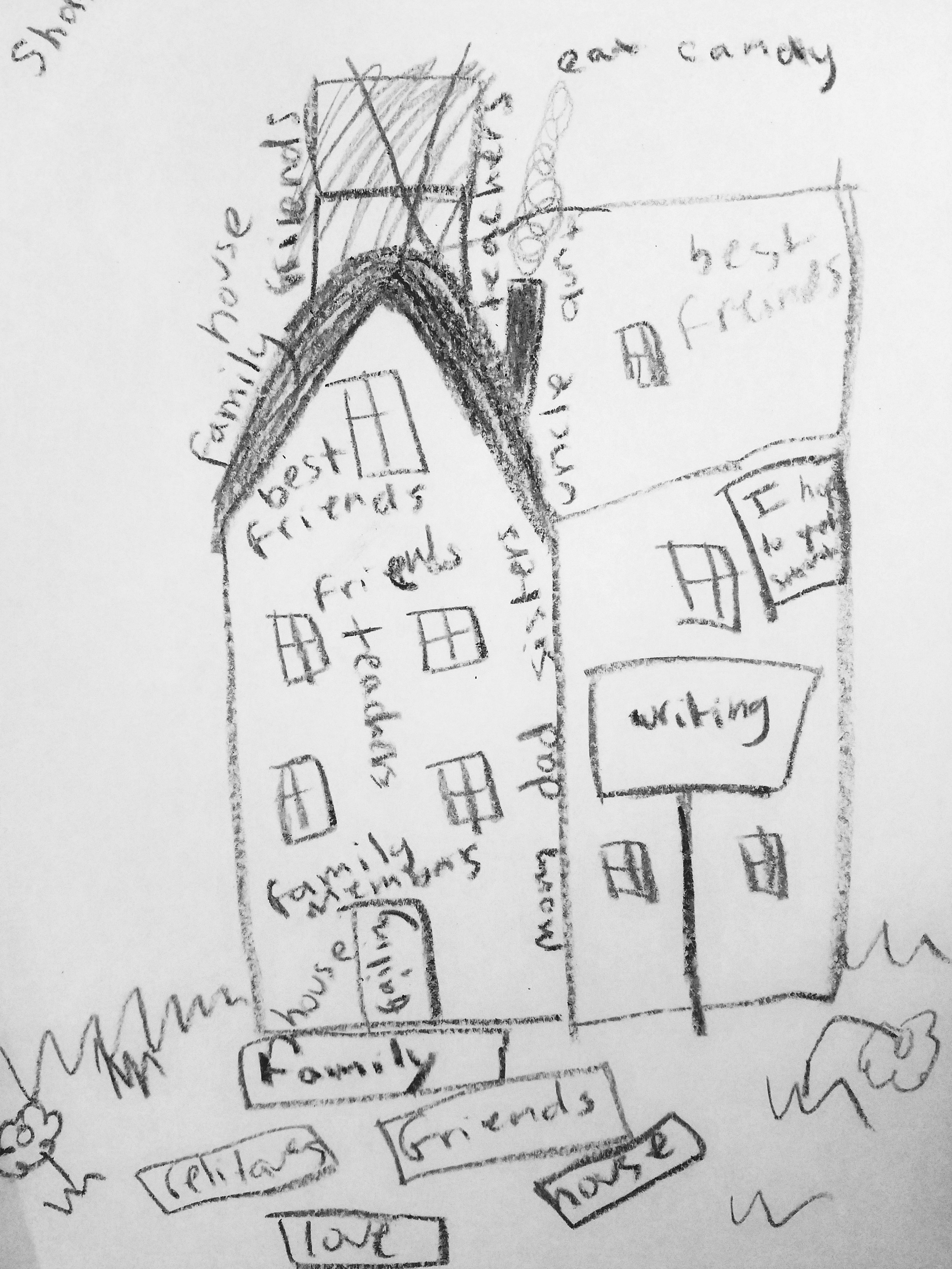

One of my favorite activities is the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, or DBT House. You can visit the activity description and view students samples HERE. The strategy is also available in the book, The Newcomer Fieldbook (Louise El Yaafouri), available HERE.

The DBT House exercise allows a glimpse into students’ lives, so that we re better able to meet them where they are. To foster resiliency, I like to follow the DBT House with this “Being Safe” lesson from Resilient Tutor Group: View it HERE.

PROMOTING ACCESS TO BASIC NEEDS AT SCHOOL

· 7 C’s of Resilience VIDEO

ANTI-BULLYING AND BULLYING PREVENTION

Non-academic foundations for learning:

· K. Brooke Stafford-Brizard @ EdWeek

REGULATION

Self-regulation leads to resiliency. Most self-regulation behaviors are learned. With this in mind, it makes sense to incorporate and model effective regulatory strategies throughout the school day. Chances are, we do this already. We may ask a student to count to 10 slowly before reacting; to self-evaluate and record distress levels; to identify “safe” spaces in the school or to diffuse disagreements with a Peace Circle.

Here are a few of my favorite techniques to use with learners of all ages.

Check out these other worthwhile resources, too!

· American Psychological Association

INCORPORATION

There are many ways to encourage students to grow in their sense of belonging at school. A great way to begin is by deliberately focusing on simple cues of belonging, such as making eye contact and referring to each child by his or her preferred (and correctly pronounced!) name. The following lessons and tools provide an entry point to promoting healthy incorporation in a school setting.

· MindSet Kit LESSONS

· MindSet Kit INTERACTIVE

EDUCATION

How can we draw from students’ existing resilience? How do we make room for bolstering new strands of resiliency in our already congested school day? We can begin by choosing resilience-building strategies that can be easily incorporated into a lesson and into the daily functioning of a classroom. Examples include:

· creating and adhering to routines (as much as possible!);

· opportunities to practice responsible choice-making (hey-hey, flexible seating!);

· brain breaks that engage students in physical exercise and creative play (GoNoodle is the bees knees!);

· learning games that encourage memory and impulse control;

· encouragement to practice safe risk-taking;

· and modeling of resilient behaviors, such as reframing disappointment.

As these tools and expectations become consistently embedded throughout students’ school experiences, they become part of the culture of the school. Ready to get started? Check out these recommended launch-points:

OVERALL TOOLBOX:

EFFECTIVE STRATEGIES FOR ACKNOWLEDGING FUNDS OF KNOWLEDGE

· North Carolina Early Learning Network

EXECTUTIVE FUNCTIONING STRATEGIES FOR STUDENTS:

· Career and Life Skills Lessons Channel VIDEO

LESSON PLANS & IDEAS FOR RESILIENCY:

Sources:

1. Pearson, Umayahara and Ndijuye. Play and Resilience: SUPPORTING CHILDHOOD RESILIENCE THROUGH PLAY A facilitation guide for early childhood practitioners

2. Sarah V. Marsden, Resilience and Belonging https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-55019-4_4

3. Taylor & Hart. The Resilient Classroom A Resource Pack for Tutor Groups and Pastoral School Staff, Published by BOND and YoungMinds.

4. Nowicki, Anna. 2008 Self-efficacy, sense of belonging and social support as predictors of resilience in adolescents Anna Nowicki Edith Cowan University

9 Cross-Curricular Writing Activities for ELLs

As summer wraps up, we find ourselves contemplating our instructional intentions for the coming school year. My big focus this year: writing.

Of the four language-learning domains (listening, speaking, reading, writing), writing is typically the last to fully develop. We can help our ELLs to develop confidence in this area by providing plenty of opportunities to practice writing skills and build writing stamina. Here are nine fantastic ways to incorporate writing into any lesson, at any grade level, and across all levels of English mastery.

CLASS MURAL

Class murals are interactive anchor charts that encourage text analysis and cooperative talk. In advance, prepare the mural "wall". A long piece of butcher paper turned lengthwise (or several strips of butcher paper taped together) works well. Depending on the class size, the mural may be 5-20 feet long. Also, a variety of print materials related to a topic should also be available- books, magazines, picture cards, student dictionaries or websites. To create the mural, first draw out background knowledge from the entire group. Then, allow students sufficient time to explore resources independently, in pairs or in teams. When ready, students will synthesize information to create a landscape on the mural that includes pictures, words, quotes, etc. To encourage language development, all illustrations should be labeled. Post mural in a visible place. Learners may add to the mural throughout a unit of study as new information is revealed. When spelling or speaking a word related to the topic, students should be asked to refer to the mural as the primary anchor chart.

FEEDBACK JOURNALS

Journaling allows students a healthy expressive outlet while practicing critical writing skills. The feedback component is what makes this strategy an effective one. Each student has a dedicated notebook to be used for the purpose of journaling for the duration of the course or unit. Students may be asked to record free thoughts, respond to direct prompts or create short summaries of daily learning or wonderings. The facilitator has the responsibility to read and respond to students' entries, offering comments, insight, clarification, grammatical notes or additional prompts. A student, in return, may also reply to or comment on the teacher's feedback. Feedback journals act as a conversation piece between the student and instructional guide, foster trust and engagement, and serve as a record of students' writing progress.

GRAFFITI

Graffiti is a cooperative exercise in which all members of a group are invited share awareness about a topic. To begin, arrange students into small cooperative work groups (3 or 5 students work best). Provide each student with a piece of butcher paper or poster-sized Post-It. Assign each group a topic or prompt that is relevant to a current unit of study. Within work groups, students will discuss and record thoughts/illustrations related to the prompt. All students are encouraged to converse and write (different colored makers- one color for each student in the group- work well for this). Use a timer to mark discussions and recording sessions. After a set period of time, rotate the posters from one group to another in a circular fashion. Each group will receive a poster that already contains student insight. Within groups, students will share thoughts on what the previous group recorded before writing new thoughts. This process continues until each poster returns to its "home" group. Posters may be reserved as anchor charts or used to further class discussion.

PARTNER DICTATION

Partner dictation is a fast-paced, simple activity that engages students in all four language-learning domains. To prepare, select a brief passage on a focus topic. Print half the number of copies as students in the class. (Or, choose unique dictation passages and print separately). For the activity, begin by pairing students. Each pair of students stands on one side of the room. Dictation passages are posted in another part of the room (or outside of the room in a hallway or corridor). One student will act as the "runner" and the other as the "recorder". (Students will have a chance to change roles). The "runner" will quickly make trips to and from the printed dictation passage to read it and return to partner to relay the message. The recorder writes what he or she hears. Students work together to edit scripts as they are being written. The runner makes as many trips to the dictation sample as needed for the recorder to capture the whole passage. Roles reverse, with a new dictation passage. Length and complexity of passages should reflect grade and language abilities present in the classroom and should be modified for pair groups as necessary.

QUICK WRITE

One key challenge for ELLs around writing is stamina. It is important to remember that students need to build up to writing longer passages. This is especially true in the upper grades, where lengthy responses are expected. Quick writes are one strategy to aid students in building stamina and structure for writing. Quick writes are set apart from other types of writing in that they purposefully omit planning, organizing, editing and revising (at least in the initial stage). The purpose of a quick write is to have students record as much relevant information related to a topic as they can in a set period of time. The writing period is intentionally limited, often beginning with only 5 or 10 minutes and working up to 15, 20 or 25-minute intervals. In the beginning stages of practices, modifications may be necessary. Early emergent students may need to copy a specific passage or use sentence stems or cloze sentences for support. More advanced students may employ a text on the topic of writing, but will be responsible for paraphrasing important information. Eventually, students will learn to write freely without significant support. To introduce a quick write, first establish a topic and time limit and then model the practice for students. It is also helpful to practice writing one document as a whole class. Finally, students write on their worn. A word bank may be useful. Quick writes should be carried out on a consistent basis and should receive some type of feedback (either from a teacher or peer). If desired, a quick write may be expanded upon to create a fully fleshed out and edited writing piece.

SAGE N’ SCRIBE

(Kagan Activity)

Sage n 'Scribe is a Kagan activity that effectively engages learners in all four language domains. Students work in pairs for this exercise. Generally, pairs use the time to work together in completing comprehension questions related to a topic. To begin, the first student (Sage) will read the first question aloud. The sage will then verbally answer his or her own question. Meanwhile, the second partner (Scribe) records the first partner’s response. The scribe also coaches the sage and/or offers feedback, if necessary. Then, the sage also records his or her response. Finally, the partners switch roles and move on to another question.

THINK-WRITE-PAIR-SHARE

(adapted Kagan strategy)

Think-Write-Pair-Share is a variation on the popular Think-Pair-Share Strategy. For Think-Pair-Share, students are asked to consider a question, given time to think about their response, and then are paired with a partner to share and discuss their reply. Adding the "write" portion deepens students thinking into the question and allows for students to explore an additional language domain. To complete the activity, facilitator poses a question to students related to a text or topic of study. Then, students are given time to process the question and think about their response. The next step calls for students to record their reply on a piece of paper or white board. When students do pair with a partner, they exchange papers. Each student reads his or her partner's contribution aloud. Within partner groups, students work together to discuss, amend, and edit responses. (Applicable texts, dictionaries, word walls or other supports may be used). Responses may be turned in, shared with other classmates, or incorporated into a graphic organizer or class anchor chart.

WRITING IN REVERSE

(based on a lesson by Jackie McAvoy)

This activity asks students to consider "comprehension" questions in order to compose a piece of writing. To complete, present students with a series of questions that are worded in the style of reading comprehension questions. Students are amused when you explain that you brought the questions to class but "lost" the reading passage. Using these questions as thinking points, they will work backward to create a composition. Working with a partner, they will first read all of the questions and write short answers to them. Then, they will use these responses to craft a full writing piece. When finished, students can exchange stories with a peer. Each learner should be able to answer the comprehension questions based on his or her partner’s writing.

WRITING WITH A MENTOR TEXT

Many English language learners can benefit from extra supports when writing. Mentor texts provide students with an exemplary piece of work to follow. They are especially helpful for intermediate and advanced students who are ready to move beyond sentence stems/cloze writing and are working toward independent writing. An appropriate mentor text should be on the same topic, length and writing style (or similar topic, length and writing style) as the piece that students will be expected to produce. Students should be guided, as a whole group or in smaller work groups, to deconstruct the mentor text. To do this, students will identify and explore key features of the text. First, have students identify the purpose of the text (narrative, expository, how-to, etc.). Next, students will explore the passage's organization (sentence structure, paragraph structure, etc.). Finally, students evaluate the "star features" of the text- meaning words, phrases, writing style, voice, figurative language or other items that make the mentor text interesting to read. Once students have had a sufficient time to digest and understand the components of the mentor text, they can use this passage to guide their independent writing.

Ready to dig deeper? These activities (and many others) were created by Refugee Classroom as part of the comprehensive EduSkills platform. Learn more at eduskills.us.

EduSkills is an educational services and school data analysis company serving schools and districts Pre-K through 12th grade. EduSkills collaborates with schools and districts in order to help teachers and administrators become high-performing outcome based educators with a clear focus on high level student achievement.

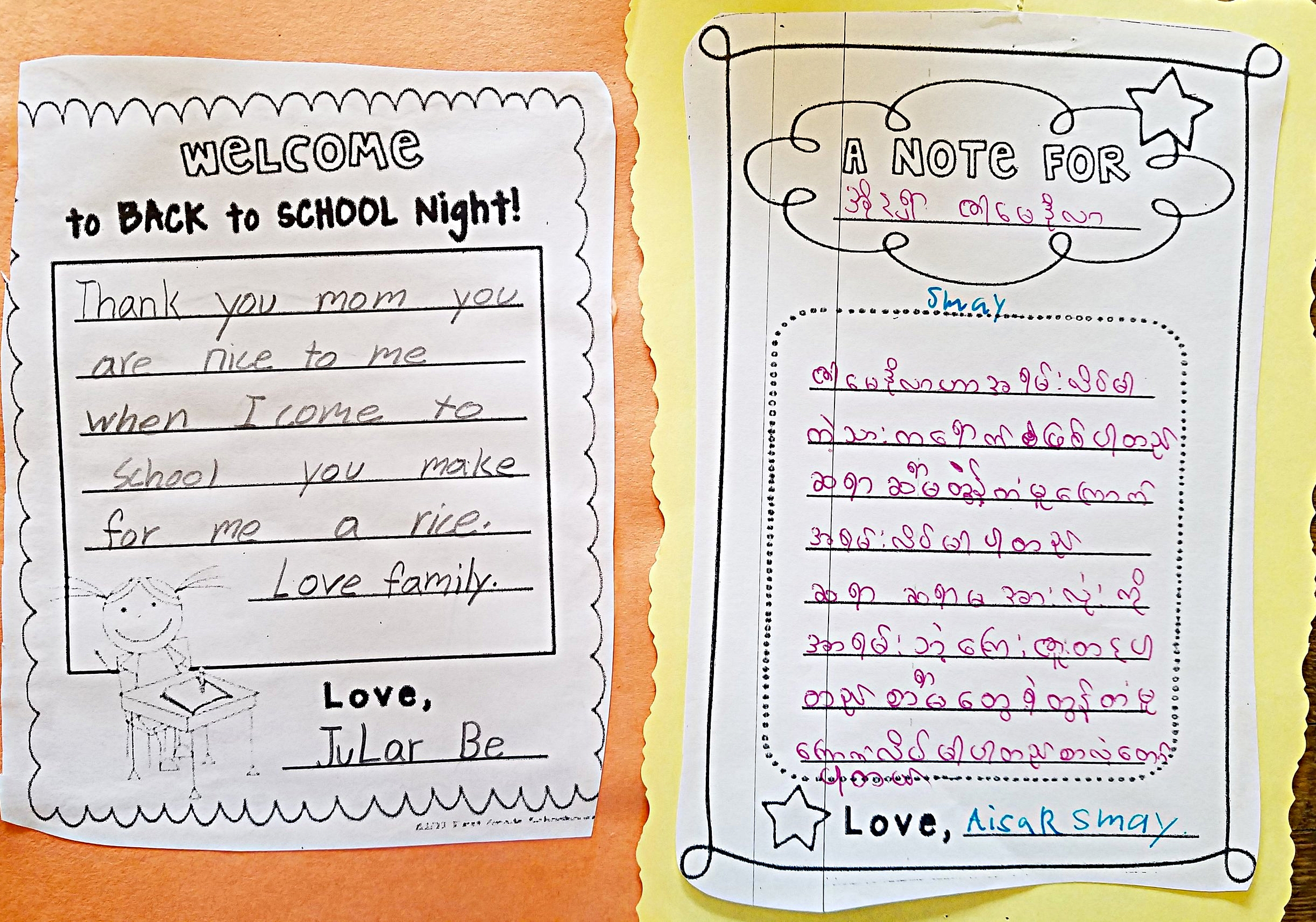

The Power of Narrative Storytelling with Emergent Multilinguals

Personal narratives can be a valuable teaching and learning tool. For refugee and immigrant language learners, the process of narrative storytelling can be especially significant, as it fulfills multiple aims. Storytelling can motivate Emergent Multilinguals to engage in the new language, develop essential writing skills, process critical life events, and foster inter-peer relationships.

Narrative expression is an essential component of our humanness. We are drawn to share pieces of ourselves through storytelling, and we discover our interconnectedness in doing so. For many of our students, storytelling is also part of a rich cultural tradition- one that is intrinsically embedded in nearly every facet of social functioning.

In the classroom, setting, we can employ personal narratives as a means to draw students into language learning. Meanwhile, we can draw out details that allow us to know and understand our students better. The strategy is helpful in that it can be implemented across the language acquisition spectrum and can be scaffolded in a variety of ways.

“Storytelling can be a very valid means to experiment with the new language in a variety of contexts. It is an accessible option at various stages of the language acquisition process, and it is a skill that can develop in accordance with a learner’s expanding linguistic capabilities.” -The Newcomer Student

Additionally, storytelling is a powerful strategy for working through transition shock. Transition shock is a broad umbrella that encompasses transition, trauma, culture shock, and stress-related anxiety. From Elements of Behavioral Health, “Talking about [experiences] helps organize memories and feelings into a more manageable and understandable psychological ‘package’. Telling the story, or developing a trauma narrative, is a significant step in the trauma recovery process no matter what array of symptoms is present.”

“There is an additional dimension to storytelling that can be profoundly cathartic and healing. The particular exercise of capturing human feelings and experiences, through fictional characters or biographical ones, allows students opportunities to release, revisit, question, and make sense of poignant life events. The retelling of personal experiences creates a fertile ground for self-discovery and social understanding.” -The Newcomer Student

Where Do We Start?

Family trees are an excellent start point. In research and focusing on the aspect of lineage, students are invited to work within a safe space, sharing what they feel is comfortable and “right” to them (this may be particularly relevant for refugee students who transition with family members who are not necessarily birth parents). This activity may also draw from parents’ existing funds of knowledge and encourage caretaker participation in students’ academic pursuits.

Incorporating heritage language is one way to increase intrinsic motivation. Constructing a family tree can also generate vocabulary connections for English words like father, grandmother, or uncle. Sharing a family tree in s safe learning space can benefit a learning community and lead to increased student ownership and self-esteem. Constructing a family tree can also generate vocabulary connections for English words like father, grandmother, or uncle.

The included samples were created by third grade students.

Heritage Books

Heritage reports, or heritage books, expand on the process of sharing students’ original stories. These are multi-step projects that “are designed to guide students in expressing their personal stories with others via sheltered instruction” (The Newcomer Student). Heritage books also enhance meaningful vocabulary expansion and promote empathic, tolerant school-based relationships.

A detailed description of heritage book planning and building is available in The Newcomer Student: An Educator's Guide to Aid Transition, available HERE.

Areas that are worthwhile to explore include:

· About Me

· U.S. Flag/flag study

· Alternative country flag(s)

· Traditional dress

· Traditional food

· Traditional customs

· Traditional housing

· Celebrities and pop culture

· Alphabet/number systems

· Family tree

· Family photos

· Emigration story

· Future hopes and wishes

The following samples are from third grade students.

“Heritage book authors are usually very eager to document, show, and share their projects with an audience. Meanwhile, they are practicing cooperative language structures and cultural normative values (handshaking and simple greetings for each guest) throughout the sharing process!” (The Newcomer Student)

Personal narratives are certainly worth including as a viable part of classroom learning and relationship building. Share your own experience enacting personalized storytelling with students to @ELYaafouriCLDE, #ELstorytelling #heritagebook

Using Sentence Starters with ELLs

The initial stages of language acquisition can be overwhelming for Newcomer learners. We can support these students (and all ELLs!) by incorporating “sheltering” techniques into our teaching practice. Sheltering strategies help to make content more accessible to language learners. Sentence starters are one type of sheltered instruction.

Sentence starters are helpful for language learners in that they can be used to scaffold both oral and written expression. Also, when learners are provided with sentence starters, they are relieved of some of the pressure to structure an entire reply. This allows students to focus on the body, or "meat", of their response.

“Sentence starters provide opportunities for ELLs to successfully participate in classroom activities in structured, purposeful ways.”

–Louise El Yaafouri, The Newcomer Student, 2016

When introducing sentence starters to learners who are within the early stages of language acquisition, it is best to limit the number of prompts to choose from. In fact, one or two options are plenty. As students grow in their language development, the number of options can be increased. With time and consistent opportunities to practice, learners will eventually develop efficacy in using a broad range of starters.

To make the most out of using sentence starters, the specific prompts should be visible to students as they are speaking and/or writing. Appropriate usage should be modeled- by the instructor, by video, or by other students, or in some combination of all of these. Eventually, students will become more independent in their production sentence starters.

As learners move closer to mastery with a particular set of sentence starters, these supports can be gradually lessened and eventually removed. Meanwhile, more complex strategies can be introduced- with new supports, if needed. Through this process of continuous scaffolding, we can guide our students closer to language proficiency and deeper content understanding.

Included is a collection of key sentence starters for academic participation. The prompts are organized into two categories: listening capacity and speaking capacity. They are suitable across grade and age levels.

Do you currently use sentence starters in your classroom? Share your experiences and contribute new prompts on Twitter @NewcomerESL #sentencestarters.

Trauma, Stress & Friend-Making

Student trauma and high levels of stress can manifest in a wide range of socio-academic challenges. As one example, complex stress can hinder friend-making. This is especially critical for EL students, as social inclusion an integral component of integration. As we strive to create trauma-sensitive learning environments for all students, we must be inclusive of the need to promote healthy social interaction and friend making.

In looking at refugee Newcomers specifically, here’s what we know: “With no other complications, it may be difficult for resettled refugee children to form healthy peer relationships in the host setting.” (The Newcomer Student, 2016). Let’s look at why.

“Newcomers face challenges in communicating thoughts and feelings in the new language, and may feel that peers do not understand them. As an added complexity, children who demonstrate elements of post-traumatic stress also score lower on the prosocial behavior scale. In other words, normative social efficacy is compromised.” (The Newcomer Student, 2016).

Friend making and self-esteem are inherently linked. Learners who feel that they have friends (or at least are largely accepted by their peers) are more likely to demonstrate healthy self-confidence. The ability to make and keep friends has academic implications, too. Students who self-identify as partners in a friendship or friendships tend to have healthier self-esteems; and learners with this type of confidence are more likely to perform well academically.

The reverse is also true: individuals who are challenged to make friends are also likely to experience difficulties in learning and participating at school. For example, “a child who has difficulty recalling, pronouncing, or ordering words in the new language is likely to experience teasing or harassment. … Teasing, in turn, can lead to shame and silence, and ultimately, to isolation. Such stalls create obvious fissures in an individual’s friend-making capacities.” (The Newcomer Student, 2016)

We know that trauma and high levels of stress negatively impact friend making (and consequently self-esteem, school satisfaction and academic success). We can also acknowledge our responsibility to aid our students in navigating social exchange as a mechanism of trauma informed instruction.

We can begin this work in the classroom using evidence-based strategies. Here’s how to get started.

1. Create safe opportunities for social engagement. Begin with pair groupings (to encourage talk and decrease the chances of a student feeling “left out”). Build up to small group engagement. Initially, schedule short periods of interaction, working up into longer ones.

2. Begin simply, with exchanges around likes and dislikes or recalling steps in a process. Invite students to find similarities in their views or observations.

3. Choose interactive activities that highlight the various strengths of students within the work-social groups.

4. Aim to initiate small group activities on a schedule, so that students can predict and better prepare themselves for interpersonal exchange.

5. During periods of sustained student interaction, listen for areas that individual students appear to struggle with or exhibit discomfort in. Work with individual students to create “social scripts” that can guide them through tricky points in a conversation.

6. Explicitly teach the meaning of facial expressions and body language. This is especially helpful for students coming from cultures where there are discrepancies in communicative gestures.

7. Avoid competitive exchanges. Instead, offer activities that promote teamwork, sharing, friendly game play and routine conversation. Have students leave personal items behind when they enter a partner or group setting, to minimize opportunities for conflict. Slowly incorporate activities that require sharing or taking turns.

8. Provide live, video or other examples of similarly aged-students engaged in normative play, conversation or group work.

9. Create structure, routine and control, but also allow students some choice and the opportunity to demonstrate self-efficacy. Anticipate that students will act in mature ways. Redirect when necessary.

10. Model how to work through conflict or disagreement. Offer sentence stems and allow students to practice these exchanges in a safe, monitored setting.

11. Prepare students to be active listeners. Emphasize the importance of active listening in a conversation. Ask students to engage in a conversation and recall details about what their partner revealed during his or her talk time. Model facial expressions and body language that indicate active listening.

12. Be mindful that some students will require additional interventions. Be prompt in processing referrals for those services. If, after a period of consistent interventions in the classroom, the student continues to struggle in social setting, request the assistance of school staff who are equipped to support the learner at a more advanced level.

Trauma and stress can impact students’ academic achievement and social wellbeing. The ability to establish and maintain friendships is a singular facet, but an important one. We can do our part to introduce tools that help our students to overcome these obstacles.

Keep in mind that our students are brilliant reminders of the resilience of the human spirit. There is always hope to be found here, and that hope is bolstered by implementation of timely, appropriate and evidence-rooted strategies in the learning context.

8 Listening-Speaking Strategies to Engage ELLs

Listening and speaking are often the first domains explored by a language learner. Students who are new to English require frequent, purposeful opportunities to develop these skills. With so many demands on our classroom time, it can be challenging to make room for dedicated speaking/listening skills practice. Fortunately, we can engage learners by embedding meaningful conversational activities in our lessons throughout the school day.

Here are eight low-prep cross-curricular activities that will get students talking (and listening, too!).

DESCRIPTIVE PAIRS

This activity encourages academic vocabulary development by engaging students in active speaking and listening around relevant classroom content. A pair of students sits back to back, with one student facing the front of the room. A category is announced (for example: mammals, text characters, types of triangles) Facilitator presents an image of one item in this category. The student facing the visual must relay to his or her partner what the image shows. In giving clues, this student must be as descriptive as possible, but cannot say the actual word or words that name the image. The student facing away from the image must engage his or her active listening skills in order to guess what the image is. When the away-facing student correctly names the image, partners hold a high-five or touching elbows and wait for other teams to solve the puzzle. Partners exchange seats and reverse speaking/listening roles.

FAN N’ PICK

Fan N' Pick is a Kagan cooperative strategy that can be used to activate background knowledge, facilitate discussion on a topic or review a concept. To prepare for activity, create a series of questions related to a text or concept. Write or type questions on strips of paper that are of similar size and shape. Place questions in an envelope. Each working group of four students will receive one envelope. Create as many envelopes as projected student groups. For lesson, arrange students into groups of four and distribute envelopes. Students in each group are numbered 1-4. Student 1 will remove the strips, making sure that all of the questions are faced down. Student 1 "fans" the strips and presents them to Student 2. Student 2 reads the strip that he or she chose and provides thinking time. Student 3 is responsible for answering the questions. Student 4 clarifies, praises, or adds on to Student 3's response. Then, the sentence strips are passed to Student 2, who becomes the new Student 1. The process repeats until all students have had a turn or all questions are answered.

INFORMATION DETECTIVE

Students work in pairs for this cooperative activity. Within pairs, each student has a card containing an image or text. The two images or passages are the same, except that each is missing some information. It is important that different information is missing on each card. Place a folder or other divider between the two students. Partners take turns asking each other questions in order to solve for the missing information on each card. New information should be recorded on the card or in a notebook. The students should not view one another's cards during the activity. Sentence starters may be useful.

LISTEN-RETELL

Listen-retell is a straightforward strategy that assesses student comprehension while working to develop learners' listening and speaking skills. For this exercise, students work in pairs. Facilitator gives each pair a prompt that is relevant to a topic being studied. One student from each pair responds to the prompt. The other student listens carefully to his or her partner's response. Then, the listening partner rephrases what was said. The first partner confirms the accuracy of the listing partner's retell. For older or more advanced students, the listening partner will rephrase the speaking partner's statement and then add on to the conversation with a new statement. After both partners have contributed, a new prompt is issues and students' speaking/listening roles are reversed.

MIX-AND-MATCH

The Mix-and-Match strategy encourages students to interact with one another in a guided format and allows for movement within the classroom. This exercise works well across all content areas. To prepare, first create a series of questions related to a topic or unit of study. Record these questions on a set of index cards. On a separate set of cards, record appropriate responses to those questions. Each question card should have a corresponding answer card. In working with older learners and/or learners with higher levels of language proficiency, it is best to incorporate student-generated questions and responses. To carry out the exercise, half of the participants are issued cards containing questions. Give the other students cards with appropriate responses to questions. Learners must move about the room sharing and comparing their cards until they find their match. Once all students have found their match, pairs may share out their corresponding questions and responses with the other students in the class.

PARTNER COACHING

Partner coaching is a cooperative strategy that allows students to practice using several or all language domains while working to solve a problem together. This activity works especially well in math or science subjects. To begin, arrange students in pairs and assign two challenges or problems to each pair of students. Each student in the pair will be responsible for solving one challenge. While the first student works on his or her problem, the second student acts as a coach, offering advice, feedback and encouragement. The coach is not permitted to write the answers or solve the problem for the first student. Students reverse roles and solve the other problem. When both challenges have been solved, one pair of students partners with another pair to form a group of four. All four students work together to confirm the validity of answers and make corrections as necessary. Note that it is helpful to model the acts of offering and accepting constructive feedback in advance. Some students may find it difficult to accept peer coaching. Make it clear that the expectation is to try to be open to feedback as possible. Offer sentence stems and other supports to guide students through the cooperative practice, as needed.

PARTNER DICTATION